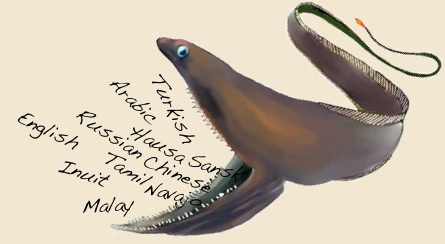

An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Overview. Austronesian is the largest language family in the world with about 1200 languages, representing one-fifth of the world's total. Its 350 million speakers are spread across an enormous territory ranging from Madagascar in the west to Eastern Island in the east and from Hawaii in the north to New Zealand in the south, including peninsular and insular Southeast Asia, most of the islands of the central and south Pacific and Taiwan. While in the western regions of Austronesia some languages are spoken by millions, the many languages of the eastern regions are spoken by few people (one thousand or less per language on average).

Austronesian languages are thought to descend from a single ancestor, spoken probably in Taiwan around 5000 years ago. As the time depth for the evolution of Austronesian languages is relatively shallow, lexically and structurally they are less divergent than one might have expected regarding the size and geographical spread of the family. Javanese, Sundanese, Malay and Tagalog are the largest Austronesian languages.

Distribution. Austronesian is spoken in Madagascar, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan, in some coastal areas of New Guinea, and in the archipelagos of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. It is also spoken in pockets on the Asiatic mainland: in southern Vietnam and southern Cambodia (Chamic languages) and on Hainan Island in southern China (Tsat language).

Map of Austronesian language groups (click to enlarge it)

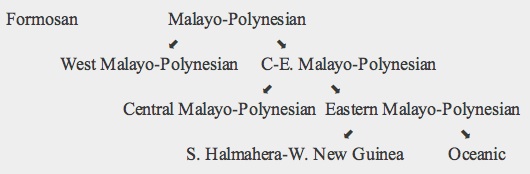

Classification and Speakers. Austronesian is divided into the Formosan languages of Taiwan, and Malayo-Polynesian that comprises the bulk of the family. Malayo-Polynesian is subdivided further as shown in the following diagram:

This is the classification scheme included in Lynch et al. (2002). In the last decade other authors have conceived somewhat different classifications. Everybody agrees that Formosan and Malayo-Polynesian are the main divisions of Austronesian. Within the latter, the existence of Central Malayo-Polynesian, S. Halmahera-W. New Guinea, and Oceanic is also usually agreed though their mutual relationships are envisaged differently. On the other hand, West Malayo-Polynesian has been divided into an Outer subgroup (Philippines languages) and an Inner subgroup (Sunda-Sulawesi languages). Thus, an alternative classification of Austronesian taking into account these latest trends (modified from Wouk and Ross, 2002) might be:

-

•Formosan

-

•Malayo-Polynesian

-

Outer Malayo-Polynesian

-

Philippines

-

Inner or Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian

-

Sunda-Sulawesi

-

Central Malayo-Polynesian

-

S. Halmahera-W. New Guinea

-

Oceanic

The classification of Bornean languages and of Malagasy (not shown above) is disputed.

Here, we maintain provisionally the Lynch et al. ordering:

1) Formosan includes several extinct and fourteen living languages of Taiwan, belonging to nine phylogenetic groups, spoken by about 300,000 people in the valleys of the central mountain chain that divides the country vertically. Before the arrival of the Chinese to Taiwan, Formosan languages prevailed all over the island but now they are all endangered.

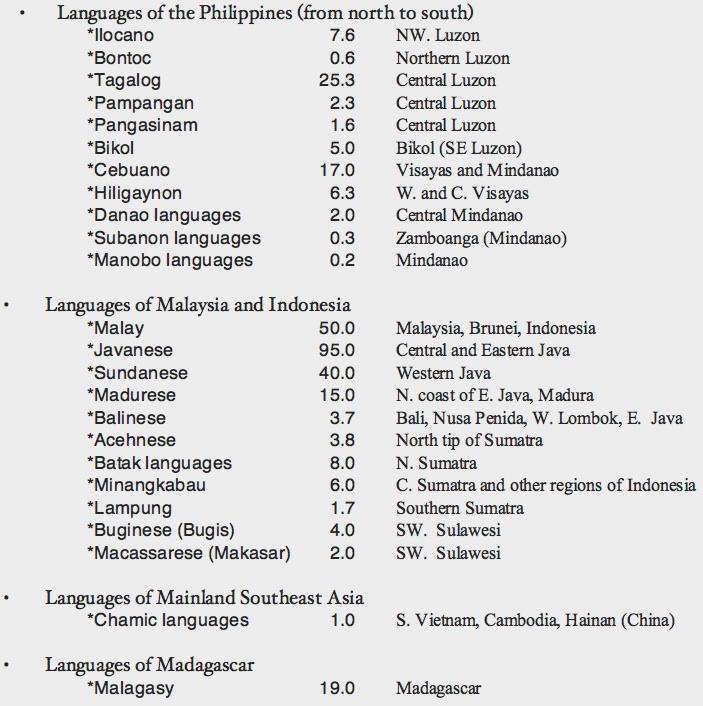

2) Malayo-Polynesian languages are divided into Western Malayo-Polynesian and Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian. Western Malayo-Polynesian is spoken in the Philippines, Malaysia and most of Indonesia as well as in Madagascar; one group of languages (Chamic) is spoken in mainland Southeast Asia and China. Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian is spoken in eastern Indonesia and in the archipelagos of Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia as well as in some areas of New Guinea. The main languages are tabulated below (speaker numbers in millions):

A. Western Malayo-Polynesian

B. Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian composed by Central Malayo-Polynesian and Eastern Malayo-Polynesian.

-

1. Central Malayo-Polynesian: includes some 50 languages spoken in the Lesser Sunda Islands of Flores, Sumba and Timor as well as in the Moluccas.

-

2. Eastern Malayo-Polynesian is divided in two branches:

-

■South Halmahera-West New Guinea with about 45 languages spoken in the southern half of the Moluccan island of Halmahera and in the Doberai Peninsula (also called Vogelkop or Bird's Head) of western New Guinea.

-

■Oceanic: The languages of this group are spoken by around 2 million people and represent almost half of all of the Austronesian languages. About 400 Oceanic tongues are spoken in Melanesia which is considered one of the regions with greatest linguistic diversity in the world. Oceanic is divided into:

-

-

•Western Oceanic includes three groups: North New Guinean, spread on the north coast of the Indonesian province of Irian Jaya, Papuan Tip languages on the southeastern peninsula of Papua New Guinea, and Meso-Melanesian in New Britain, New Ireland, the northern tip of Bougainville, and the western Solomon Islands. Two relatively large Western Oceanic languages are Western Tolai, spoken by 60,000 people in the eastern end of New Britain, and Motu, spoken by 40,000 people in the south coast of New Guinea.

-

-

-

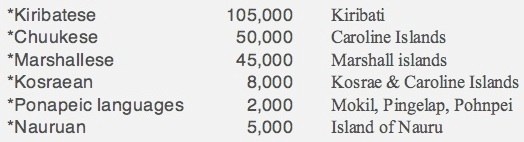

•Central-Eastern Oceanic is divided into Micronesian, Southeast Solomonic, New Caledonian-Vanuatu, and Fijian-Polynesian subgroups.

-

-

Micronesian languages: some of them can extend to neighboring islands while others are restricted to a single island. Nauruan is the most peripheral member of the group.

-

Southeast Solomonic includes some 25 languages spoken in Santa Isabel, Guadalcanal, Malaita, Makira and other eastern islands of the Solomon Archipelago (the languages of the western Solomons belong to Western Oceanic).

-

The New Caledonian-Vanuatu group (also called Southern Oceanic Linkage), spoken by about 300,000 people, comprises the more than 100 languages of the Vanuatu archipelago and the 40 languages of the New Caledonian archipelago (which includes the main island Grande Terre, the Loyalty Islands, and several smaller ones).

-

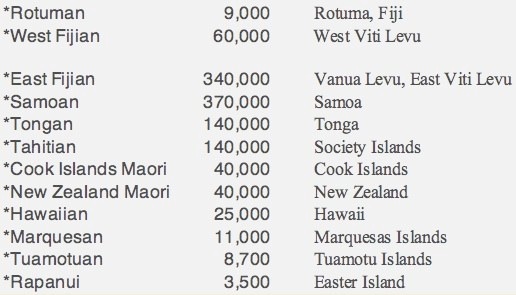

Fijian-Polynesian (also called Central Pacific Linkage) can be divided into a Rotuman-West Fijian branch and an East Fijian-Polynesian branch. Adding up its two varieties, Fijian has 400,000 speakers, being the largest language of the group. Polynesian languages often extend over neighboring islands. There are about forty of them. The main Fijian-Polynesian members are:

-

-

•Yapese, a single language spoken by 7,000 people in the island of Yap which belongs to the Caroline archipelago. It might be related to the Admiralty languages.

-

-

-

•Admiralty Islands languages, with some 30 members, scattered in 18 islands belonging to the Bismarck archipelago.

-

-

•Saint Matthias Islands languages, including Mussau-Emira and the almost extinct Tenis, spoken in a group of small islands belonging also to the Bismarck archipelago. They might be related to the Meso-Melanesian group of Western Oceanic.

-

-

•Temotu composed of Reefs-Santa Cruz, Utupua, and Vanikoro languages, spoken on islands to the southeast of the Solomons.

-

Status. Malay is a lingua franca in the Indonesian archipelago and the national language of Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. Tagalog is a lingua franca in the Philippine archipelago and the national language of the Philippines. Tahitian is a lingua franca throughout French Polynesia. Samoan, Tongan and Fijian are national languages of independent states.

SHARED FEATURES

Structurally, Formosan and Western Polynesian languages are close, but Micronesian has undergone extensive phonological and lexical changes.

-

✦ Phonology

-

-Content words typically have two syllables (disyllabic). Consonants tend to alternate with vowels in CVCV sequences.

-

-Most languages have four or five vowels. A four-vowel system, constituted by i, u, ə, a, has been reconstructed for Proto-Austronesian.

-

-Consonant inventories are variable but they are remarkably small in Polynesian languages. Among them, Hawaiian has just eight consonants (p, k, glottal stop, h, m, n, l, w).

-

-Austronesian languages have a restricted range of consonant clusters. The combination of a nasal + stop is the most common, being treated as a single prenasalised consonant in Oceanic languages.

-

-Most Austronesian languages do not allow final palatal consonants. In some of them restrictions on final consonants are more severe, like in Macassarese where only the velar nasal and the glottal stop are permitted. Many Oceanic languages end always in a vowel as a result of the loss of final consonants or of the addition of a 'supporting' vowel.

-

-Tones are almost absent in contrast to the prevalence of them in many neighboring Asian languages.

-

✦ Morphology

-

-To indicate possession nouns are suffixed with a pronominal marker.

-

-Reduplication may be used to mark number and verbal aspect.

-

-Nouns can be derived from verbs by affixation.

-

-Verbs are stative or dynamic. Stative verbs ('to be afraid', 'to be happy', etc) are used as adjectives which don't exist as an independent category in Austronesian.

-

-Transitivity, voice and focus (see below) are usually indicated by the use of affixes.

-

-Most Austronesian languages of Taiwan, the Philippines and Sulawesi have a complex verbal morphology expressing by means of affixes the 'focus' of the phrase. For example, in Tagalog the verb may be marked for focus on the actor, on the patient, on location or on instrument. When that happens, the noun that is the focus of the phrase is also marked.

-

✦ Syntax

-

-Word order is in general verb-initial or verb-second, and prepositions are used. The great majority of Formosan and Philippine languages are Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) or VOS. Polynesian languages and Fijian are also VOS, but other languages of the Pacific and most Indonesian languages are SVO. Exceptionally, most Austronesian languages spoken in the Papuan tip, as well as some in the northern coast of New Guinea, are SOV and use postpositions, features normally associated with neighboring Papuan languages and, most likely, acquired because of prolonged contact with them.

-

-To distinguish common from proper nouns, articles are used preceding the noun which is followed by adjectives and relative clauses.

-

✦ Lexicon

-

-Comparative analysis of the vocabulary of different Austronesian languages has allowed the reconstruction of about five-thousand words springing from a common stock. They picture a people who practiced agriculture (cultivating rice and millet, taro and yams), had domesticated animals, knew many tropical fruits, were familiar with the sea and lived in raised houses erected in villages.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-The Austronesian Languages of Asia and Madagascar. A. Adelaar & N. P. Himmelmann (eds). Routledge (2005).

-

-The Oceanic Languages. J. Lynch, M. Ross & T. Crowley. Routledge (2002).

-

-The History and Typology of Western Austronesian Voice Systems. F. Wouk & M. Ross (eds.). Australian National University (2002).

-

-'Austronesian Languages'. R. Clark. In The World's Major Languages, 781-790. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-'Austronesian Languages'. R. A. Blust. In Encyclopædia Britannica Ultimate Reference Suite (2011).

-

-The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. P. Bellwood, J. J. Fox & D. Tryon. Australian National University Press (2006).

Austronesian Languages

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania