An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Afroasiatic, Chadic, West Chadic. Hausa closest relatives are other members of the West Chadic group, specially Angas and Bole.

Overview. Hausa is the largest member of the Chadic family and, with Swahili, it is one of the two most important languages of sub-Saharan Africa. It is spoken by the majority of the inhabitants of northern Nigeria and of the Republic of Niger. Not only it has, by far, the greatest number of native speakers of any Chadic language, but it is also used as a lingua franca for trade and commerce in many parts of Central Africa. Exceptionally within Chadic, Hausa is regularly written and has developed a literature.

It employs tones to mark grammatical forms and it has many consonants due to the occurrence of secondary articulations. The verbal system is remarkable for having preverbal complexes, inflected for person and tense-aspect, preceding invariable stems. Hausa sentences have the typically Chadic subject-object-verb word order.

Distribution. Native speakers of Hausa live mainly in northern Nigeria and southern Niger. Some have migrated to Benin, Ghana, Cameroon and Sudan.

Speakers. Hausa is the mother tongue of about 35 million people and the second language of 20 million or more. About 27 million native speakers live in Nigeria, 6.8 million in Niger and one million in Benin.

Varieties. Dialect variation is not great but three dialect groups can be distinguished:

-

*Eastern Hausa (in Kano), which is the Hausa standard.

-

*Western Hausa (in Sokoto and Gobir).

* Niger dialects (Aderanci and others).

Status. Even if Hausa is not an official language in Nigeria or Niger, it is there the educational language in primary schools, it is widely used in the media and has an extensive literature, being also used in government and commerce. For higher education, English and French are preferred in Nigeria and Niger, respectively.

Phonology

Syllable structure: no consonant clusters occur within a syllable. Three types of syllables are possible: CV (light), CVV (VV can be two vowels or a diphthong), and CVC (heavy).

Vowels (12). The vowel system has 10 monophthongs and two diphthongs.

-

*Monophthongs: consist of short and long i, e, a, o, u. Contrast between short and long vowels is important lexically and grammatically.

-

*Diphthongs: ai, au.

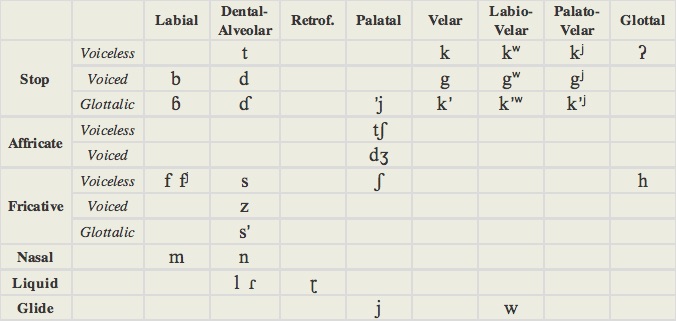

Consonants (32). Hausa has numerous consonants due to the presence of:

-

a) a glottalic series contrasting with the voiceless and voiced ones.

-

b) palatalized and labialized velars alongside simple ones.

The glottalic consonants are realized as implosives (ɓ, ɗ), ejectives (kʼ, kʼʷ, kʼj, sʼ) and a glottalized glide (ʼj). Hausa does not have a p sound. It has two distinct rhotics: a retroflex flap and an apical tap or roll. All consonants can occur as geminates (double consonants).

-

Note: a j superscript indicates palatalization; a w superscript indicates labialization.

Tones: Hausa is a tonal language. It has two basic tones (high and low) and a composite one i. e. a sequence of high and low tones on a single syllable that is realized as a falling tone. Tones are not marked in the standard orthography, but in linguistic works low tone is marked by a grave accent, high tone with an acute accent (or left unmarked) and falling tone with a circumflex one.

Script and Orthography.

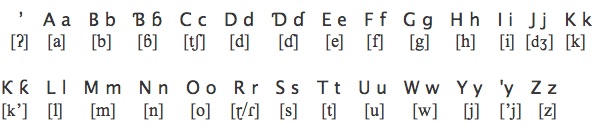

Hausa was written first in the Arabic script (àjàmí) which in the early 20th century started to be replaced by a Latin script called bóokòo (from a Hausa word meaning 'fraud' or 'sham'). However, àjàmí is still widely used in Koranic education and for poetry and is regaining popularity in the media. In bóokòo, tone and vowel length are not marked and the difference between the two rhotics is ignored. Bóokòo has 27 letters (22 consonants and 5 vowels). Many basic sounds are represented by digraphs which are usually handled as sequences of two letters in the alphabetic order. Below each letter its equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown.

-

•tone is not represented in standard orthography but may be indicated by grave, acute and circumflex accents.

-

•long vowels are not distinguished orthographically but in scholarly and didactic publications they are written twice or represented with a macron.

-

•long consonants are represented by doubling.

-

•the labio-velars are represented by digraphs: [kʷ] by kw, [gʷ] by gw, and [kʼʷ] by ƙw.

-

•the palato-velars are represented by digraphs: [kj] by ky, [gj] by gy, [kʼj] by ƙy.

-

•[fj] is represented by the digraph fy.

-

•the glottalized fricative [sʼ] is represented with the digraph ts.

-

•the palatal fricative [ʃ] is represented with the digraph sh.

-

•the glottalized glide [ʼj] is represented by the digraph 'y in Nigeria and with the special character ƴ in Niger.

-

•the two rhotics are not distinguished in the orthography; in scholarly publications the alveolar tap [ɾ]is represented r̃ to distinguish it from the retroflex flap [ɽ] represented as r.

-

•p is used in foreign names and words.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Nouns and adjectives are inflected for gender and number.

-

•gender: masculine and feminine are distinguished only in the singular. Masculine words are usually unmarked and feminine ones end in aa, yaa or waa.

-

•number: singular and plural. Plural formation is complex and not totally predictable. It is determined by the insertion of vowels, addition of affixes, reduplication or tone change.

-

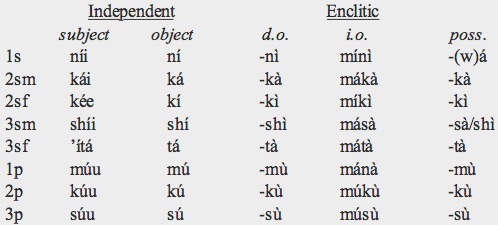

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

Personal pronouns may be independent or enclitics. The former have subject and object forms, the latter have direct object, indirect object, and possessive forms.

-

They distinguish gender in the 2nd and 3rd persons of the singular.

-

Subject pronouns may serve also as direct object when not immediately following the verb. Independent direct object pronouns mark the direct object of verb grades 1 and 4 (see below). Direct object clitics are used as direct objects of other verb grades; they are formally similar to the independent ones but their tone is low instead of high. Indirect object pronouns are similar to direct object pronouns but bound to the indirect object marker má which assimilates its vowel to the enclitic. The possessive enclitics are suffixed to the masculine and feminine markers na and ta originating two series of gender-marked pronouns.

-

Non-personal pronouns (demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite) are all marked for gender and number.

-

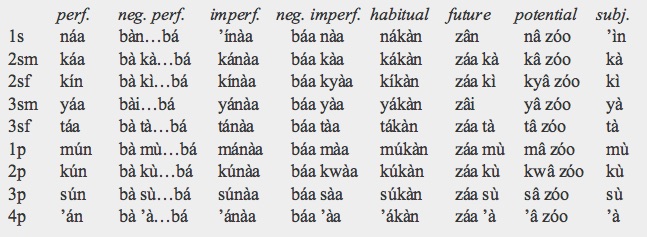

Verbal. Almost all Hausa verbs end in a vowel and are invariable (except in the imperative). The two categories of subject agreement (person, gender and number) and TAM (tense, aspect, mood) are marked via a preverbal complex. The first element of this complex is a variant form of a personal pronoun and the second is a TAM marker, both are sometimes fused and the individual morphemes are not always separable. In addition to the eight personal forms each paradigm contains an impersonal form (called 4th plural) used when there is no overt subject.

-

•Hausa verbs express aspect more than tense and the major division is between perfective and imperfective aspects. The perfective aspect indicates a completed action and tends to be associated with the past tense. The imperfective aspect indicates an incomplete or ongoing action and can have a present or future sense. The habitual is another aspect, one without a specific temporal dimension, indicating a regular action performed in the past, present or even the future. The future has also an aspectual dimension, indicating an action taking place after a specified time and, thus, may be used with reference to past time; it can also be employed in conditional clauses.

-

•The subjunctive and potential are more modal than aspect-tense categories. The first one is used to give commands and permissions, for greetings, to express an intention or suggestion, a wish or a proposal. The second indicates that an action will possibly take place and for that reason is also called indefinite future, but differs from the normal future because of its uncertainty and/or lesser commitment.

-

•The imperative is the only TAM marked directly on the verb. It is restricted to the 2nd person singular (without gender distinction). It is usually indicated by a low-high tone pattern overriding the tone pattern of the verb. It is used, like the subjunctive, to give commands (but the subjunctive has other functions which are outside the field of the imperative).

-

•Besides the affirmative TAM forms, there are also negative ones and some that are specific for focus constructions. Below, we show the main preverbal complexes, including two negative ones:

-

In the future the usual order of the preverbal complex is reversed; the subjunctive has no TAM marker. Negation of the perfective and the future requires two negative markers: the first one is placed immediately before the preverbal complex while the second is placed at the end of the clause. In contrast, the imperfect negative requires just one negative marker.

-

•An ongoing action can also be expressed by verbal nouns functioning as a sort of present participle.

-

•Hausa verbs have a derivational system comparable in some measure to that of Semitic verbs. They are classified in seven "grades" according to their final vowel and tonal pattern.

-

‣grade 1 are transitive or intransitive as well as ‘applicatives’ that serve to transitivize intransitive verbs.

-

‣grade 2 includes basic transitive verbs and derived ones with a partitive sense.

-

‣grade 3 has exclusively intransitive verbs.

-

‣grade 4 verbs indicate an action totally done or affecting all the objects.

-

‣grade 5 verbs end in the consonant r and are causative serving mainly to transitivize intransitive verbs. They may also indicate an action away from the speaker.

-

‣grade 6 'ventive' verbs indicate movement towards or in benefit of the speaker.

-

‣grade 7 verbs express a middle voice or impersonal passive, a well-done or sustained action.

-

Each grade has three syntactical forms A, B, and C. B when the verb is followed by an object pronoun, C when it is followed by another direct object, and A when it has no object.

Syntax

Hausa has a quite strict word order which is, like in most Chadic languages, SVO: Subject-Verb-Indirect Object-Direct Object. An overt noun phrase subject is not essential and may be omitted (pro-drop language). Adjectives precede their nouns and agree with them in gender and number. Attributive numerals follow the noun. Possession is indicated by means of a suffix attached to the noun that is possessed i.e., the possessee (n for masculine or plural, r̃ for feminine); thus the 'boy’s grandfather' is expressed in Hausa: kàaká-n yáaròo (‘grandfather-of boy’).

There are no definite or indefinite articles, definiteness is determined by context. Indefiniteness can be indicated by the use of the words wání (m), wátá (f), wású (pl) equivalent to ‘some’. In interrogative sentences, the interrogative word occurs in initial position and the preverbal complex is marked for focus. Focus-marking is also required in relative clauses which are preceded by the relativizer particle dà. Focus constructions are also used to emphasize a nominal phrase, personal pronoun or adverb.

Lexicon

Hausa has absorbed a vast number of loanwords. Overall, the major influence has been Arabic. In the semantic spheres of religion, government, administration and literature, words of Arabic origin are predominant. More recently English has had a pervasive influence in Nigeria while the same has happened with French in Niger. Other contributors have been Nigerian and Nigerien languages like Kanuri, Yoruba and Fula, and north African ones like Mande and Tuareg. Hausa, like many African languages, has a special class of words with particular sound characteristics, called ideophones, associated with vivid sensory or mental experiences.

Basic Vocabulary (tones not shown)

one: ɗaya

two: biyu

three: uku, ukku

four: huɗu

five: biyar

six: shida, shidda

seven: bakwai

eight: takwas

nine: tara

ten: goma

hundred: ɗari

father: uba

mother: uwa

brother: ɗan'uwa

sister: ƙanwa

son: ɗa

daughter: 'ya

head: kai

face: fuska

eye: ido

hand: hannu

foot: ƙafa

heart: zuciya

tongue: harshe

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

-

Further Reading

-

-'Hausa and the Chadic Languages'. P. Newman. In The World's Major Languages, 618-634. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-Referenzgrammatik des Hausa. E. Wolff. Hamburger Beiträge zur Afrikanistik. Lit. Verlag (1993).

-

-The Hausa Language: An Encyclopedic Reference Grammar. P. Newman. Yale University Press (2000).

-

-Hausa. P. J. Jaggar. London Oriental and African Language Library, 7. John Benjamins (2001).

Hausa

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania