An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Modern Indo-Aryan, Central.

Overview. Hindi is the largest language of India and the second largest in the world (after Chinese). Very similar to Urdu, they are separated by political, cultural and religious differences. Although Hindi descends ultimately from Sanskrit, its grammar, like those of other Modern Indo-Aryan languages, is far simpler. Exposed to multiple foreign contacts, it incorporated a vast array of words derived from Persian, Arabic, English and Portuguese, among others.

Distribution. Northern and central India, particularly in the states of Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, the city of Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, and Jharkhand (in the last two states most people speak Bhojpuri, Magahi, and Maithili closely related to Hindi). There are also substantial numbers of Hindi speakers in Nepal, the Caribbean (Guyana, Suriname, Trinidad & Tobago), in Africa (Mauritius, Uganda, South Africa) and the Pacific (Fiji).

Speakers. Hindi is the mother tongue of over 40 % of the total population of India and, besides, is spoken by many as a second language. There are more than 500 million speakers of Hindi (including all dialects and related languages except Urdu and Maithili) in the following countries:

India

South Africa

Mauritius

Guyana

Fiji

U.S.A

Yemen

Suriname

Uganda

Nepal

Trinidad & Tobago

Singapore

505,000,000

890,000

695,000

600,000

450,000

317,000

233,000

200,000

147,000

120,000

20,000

5,000

Status. Hindi is one of the 23 official languages of India and, alongside English, is the national language of the country.

Varieties. The normative form of Hindi, promoted by the government and taught in schools, is called Modern Standard Hindi (MSH). The most important varieties are Braj (in the area of Agra), Avadhi (around Oudh), Rajasthani (in the state of Rajasthan), Bhojpuri (around Varanasi), Magahi (around Patna and in southern Bihar), and Maithili in northeastern Bihar (the latter is usually considered as a separate language and its speakers are not included in the table).

Related languages are Hindustani, Urdu and Khari Boli (Delhi speech). Hindi's grammar is almost identical to that of Urdu but there are substantial differences in their vocabularies, scripts, and religious and cultural backgrounds, so they are considered as different languages.

Oldest Documents

1150-1200. Prithiviraj Raso, a courtly epic of Delhi.

1200-1300. Dhola Maru and other early epics of Rajasthan.

c. 1300. Poetic compositions of Amir Khusrau (1236-1324).

Phonology

Vowels (10). Hindi has a ten vowel system composed of three lax and seven tense vowels. Lax vowels (ɪ, ʊ, ə) are phonetically short and tense vowels (i, e, ɛ, u, o, ɔ, ɑ) are phonetically long. [ɪ] is slightly lower and more centralized than [i], [ʊ] is slightly lower and more centralized than [u]. All have nasal forms. Oral and nasal vowels are contrastive (for example: hɛ ('is') versus hɛ̃ ('are'); bɑs ('foul smell') versus bɑ̃s ('bamboo').

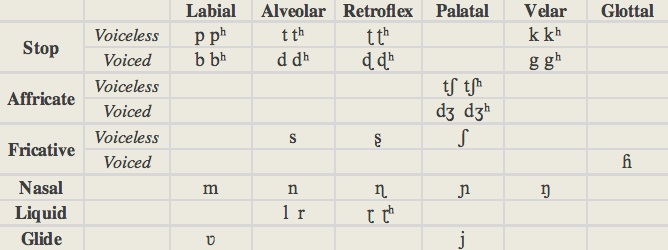

Consonants (35). Hindi has 35 consonants in total, including 20 stops, 4 fricatives, 5 nasals, and 6 liquids/glides. The stops and nasals are articulated at five different places, being classified as labial, alveolar, retroflex, palatal and velar. The palatal stops are, in fact, affricates. Every series of stops includes voiceless and voiced consonants, unaspirated and aspirated, this four-way contrast being unique to Indo-Aryan among Indo-European languages (Proto-Indoeuropean had a three-way contrast only).

The retroflex consonants of Hindi, articulated immediately behind the alveolar crest, are not from Indo-European origin though present already in Sanskrit. They are, probably, the result of Dravidian language influence. Hindi has, also, a retroflex liquid (unaspirated and aspirated) not inherited from Sanskrit. [ʋ] is pronounced as v or w depending on context.

Stress: usually falls on the penultimate syllable. It is not phonemic, i. e. words are not distinguished based on stress alone.

Script and Orthography

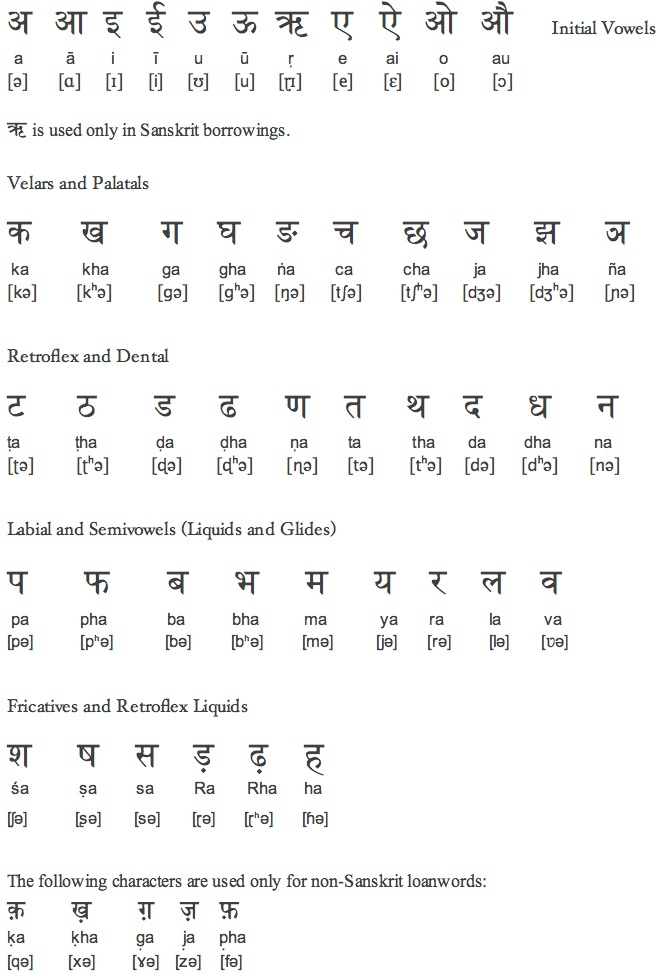

Today Hindi is written in Devanāgarī, an abugida (syllabic alphabet) employed also for Marathi, Nepali and Sanskrit, derived ultimately from Brāhmī, one of the first scripts of India. Up to the beginning of the 20th century the Perso-Arabic script was used alongside Devanāgarī and local scripts.

The Devanāgarī alphabet consists of 46 letters arranged according to phonetics and reproducing the order of Brāhmī. First, come the simple vowels, which are followed by the diphthongs (e and o derive from ancient diphthongs and were considered so by the ancient grammarians). After the vowels come the stops and nasal consonants divided into five groups (each of five letters) according to their place of articulation (from back to front). Within each group the order is: voiceless unaspirated stop, voiceless aspirated stop, voiced unaspirated stop, voiced aspirated stop, nasal.

After these five groups, follow the semivowels (liquids and glides) also arranged according to their place of articulation. Finally, the fricatives starting with the sibilants. Below each letter the standard transliteration is shown followed by its International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) equivalent between brackets:

Morphology

-

Nominal. Nouns are inflected for gender, number and case. Adjectives are of two types: declinable and indeclinable. Declinable adjectives agree in case, number and gender with the nouns they qualify. New words are formed by derivation and compounding.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine. Most masculine nouns end in ā and most feminine ones in ī, but noun gender cannot always be predicted.

-

•number: singular, plural.

-

•case: direct and oblique. The first one is used for subject and direct object. The second is used for nouns accompanied by postpositions (similar to English prepositions but placed after the noun they modify) which serve as markers for other syntactical functions. Certain nouns have also a special vocative form. All nouns belong to just two declensional types per gender. Masculine class I nouns end in ā while masculine class II nouns may end in other vowels or in a consonant:

-

Some masculine nouns ending in -ā behave like Class II nouns. For example pitā (father): direct sg. or plural pitā, oblique sg. pitā, oblique plural pitaõ.

-

Feminine class I nouns end in ī while feminine class II nouns may end in other vowels or in a consonant:

-

•adjectives: masculine declinable adjectives end in ā in the direct singular and in e in all other cases; feminine adjectives, singular or plural, end always in ī.

-

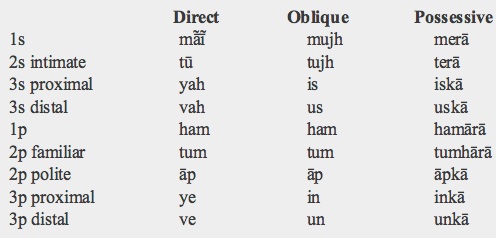

•pronouns: personal, possessive, reflexive, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite, relative.

-

Personal pronouns are genderless and do not have a form for the 3rd person, which is provided by the distal demonstrative pronoun. The 2nd person pronoun differentiates three degrees of politeness: intimate, familiar and polite. The last two, even if they are technically plural, can refer to a single individual. They have direct, oblique and possessive forms:

-

Possessive pronouns may also function as adjectives, agreeing with nouns in gender, number and case e.g. merā beṭā ('my son'), merī beṭī ('my daughter').

-

There is one proximal demonstrative pronoun and one distal: yah ('this'), vah ('that'), ye ('these'), ve ('those'). For example: yah pustak ('this book'), vah pustak ('that book'), ye pustakẽ ('these books'), ve pustakẽ ('those books').

-

Interrogative pronouns are kaun ('who?') and kyā ('what?'). The latter when standing at the beginning of a sentence marks a yes/no question (being equivalent to a question mark and not to 'what?'). Other interrogative words are kyõ ('why?'), kab ('when?'), kahā̃ ('where?'), kidhar ('in which direction?').

-

Hindi has three indefinite pronouns. Kaī ('several, a number of, some') is always plural and it is used to refer to an unspecified number of persons, animals or objects; it is limited to countable entities and has no oblique form. Koī ('any, some') is always singular and kuch ('some, a few') may be singular when referring to a non-countable noun or plural to refer to an undifferentiated group of countable entities.

-

The relative pronoun is jo ('who, what, which'). This direct case form is the same for the singular and plural but the pronoun has different oblique singular and plural forms (jis and jin, respectively). Relative clauses may precede or follow the main clause.

-

•articles: Hindi has no articles but demonstrative pronouns can function as such.

-

•postpositions: are used to indicate the syntactic role of a noun, indicating case relations. They can be simple or compound. The main ones are:

-

ko: 'to', marks the direct object (accusative) and indirect object (dative).

-

se: 'by, with, from' (instrumental, comitative, ablative).

-

mẽ: 'in'; par: 'on' (locative).

-

kā: 'of' (possessive, genitive).

-

ke: is a marker of inalienable possession.

-

For example:

-

Us laRke ko tīn rupaye dijiye.

-

that boy to three rupees give

-

'Give three rupees to that boy.'

-

LakRī se mezẽ bantī hãĩ.

-

wood from tables made are

-

'The tables are made of wood.'

-

Kuẽ mẽ kuch pāni hai.

-

well in some water is

-

'There is some water in the well.'

-

Vah pensil mez par hai.

-

that pencil table on is

-

'That pencil is on the table.'

-

Rām kā beṭā.

-

Ram of son

-

'Ram's son'.

-

Skūl ke adhyāpak.

-

school of teacher

-

'The teacher of the school'.

-

Verbal. The quite regular verbal system of Hindi is structured around combinations of aspect and tense. Conjunct verbs (noun or adjective + verbs 'to be' or 'to do') and compound verbs (lexical verb + subsidiary verb) are frequent. Another noteworthy feature of the Hindi verbal system is the existence of verb sets that have morphologically related stems and convey related meanings i.e., intransitive, transitive and causative.

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p.

-

•aspect: imperfective (including habitual and continuous actions) and perfective (completed activities).

-

•mood: indicative, presumptive, subjunctive, imperative.

-

The presumptive and subjunctive are considered an integral part of the tense system. Only the imperative is considered an independent mood. There are several imperatives depending on familiarity, politeness, and imminence of the action commanded:

-

Intimate: it is an order addressed to the 2nd person singular, tū, using the uninflected verbal stems (jā! ['go!']).

-

Familiar: it is an order addressed to the 2nd person plural familiar, tum, and it is formed with the stem plus the suffix -o (āo! ['come!']).

-

Polite: it is used for requests when the addressee is 2nd person polite āp. It is formed with the stem plus the suffix -ie/-iye (dhoie ['please wash']).

-

Deferential: used when the addressee is treated with greater politeness. It is formed with the stem plus -ie plus the invariable suffix -gā (likhiegā ['please be so kind as to write']).

-

There is another form, the deferred, used when the action is meant to be carried out later, it is equal to the infinitive (formed with stem plus the suffix -nā).

-

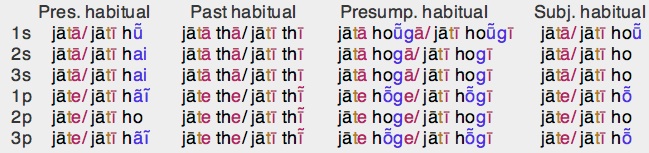

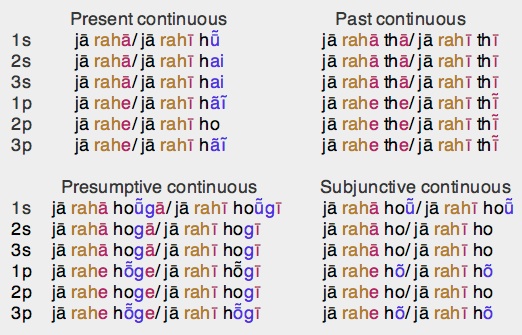

•tense: aspect, mood and tense are inextricably bound. There are twelve aspectual tenses which combine the main lexical verb, marked with one of three aspects (habitual, continuous, and perfective), with different tenses of the verb honā ('to be') (present, past, presumptive and subjunctive). The main verb indicates gender and number while the copula indicates person and number. However, in the past the copula behaves as an adjective agreeing in gender and number with the subject without indicating its person.

-

Two additional verb forms, the root subjunctive and the future, are non-aspectual. There are also aspectual forms without indication of tense, namely the simple perfective.

-

The habitual aspect is marked by the affix -t- added to the main verb root, the continuous aspect is marked by the auxiliary rah- ('remain') and the perfective aspect is expressed by the naked verb root.

-

The habitual aspect indicates that an action is done regularly in the present ('she goes home daily') or in the past ('she used to go home daily'); in the presumptive the habitual action is presumed ('she would be going') and in the subjunctive it is hypothetical ('I want her to go'). The following are the habitual conjugations of jānā ('to go'):

-

black: verb root; brown: aspect marker; red: gender and number marker (ā for masc. sg, e for masc. pl., ī for fem. sg and pl.), blue: personal endings.

-

In the continuous tenses aspect marking is conveyed by the root of a second auxiliary verb. Thus, they have three components: main verb root + aspect marker rah- ('stay, remain') + different tenses of honā. Gender and number are marked on rah- instead of on the main verb.

-

The continuous aspect expresses that an action is in progress in the present ('I am going') or was in progress in the past ('I was going'). In the presumptive, an action is presumed to be occurring ('she must be going'), and in the subjunctive, the action is hypothetical ('she would be going').

-

black: verb root; brown: aspect marker; red: gender and number marker (ā for masc. sg, ī for fem. sg and pl., and e for masc. pl.); blue: personal endings.

-

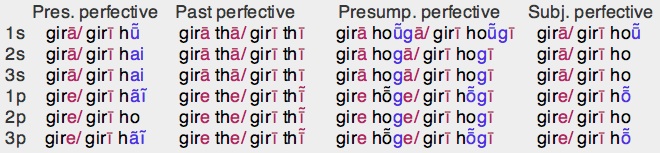

The perfective aspect indicates that an action has been completed. The present perfective indicates that the effect of the completed action is still felt in the present ('it has fallen'). In the past perfective the effect of the completed action is not relevant to the present ('it had fallen'). The presumptive perfective refers to an action presumed to have been completed but not directly known ('it must have fallen'). The subjunctive perfective expresses the hypothesis that an action may have been completed ('it is possible that it has fallen').

-

The conjugation of girnā ('to fall') is as follows:

-

black: verb root: red; gender and number marker (ā for masc. sg, ī for fem. sg and pl., and e for masc. pl.); blue: personal endings.

-

There is also a simple perfective or simple past, which only marks gender and number, and doesn't need an auxiliary verb. Thus, girnā has just four forms like an adjective: girā (masc. sg.), gire (masc. pl.), girī (fem. sg.), girī̃ (fem. pl.).

-

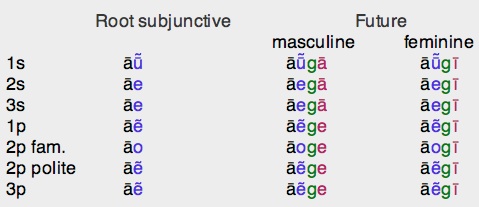

The root subjunctive and the future are non-aspectual tense forms. The first one is formed with the addition of specific suffixes to the stem (1s: -ū̃; 2s and 3s: -e; 2pl familiar: o; 1pl, 2pl polite and 3pl: -ẽ). It is used in constructions meaning 'as if', or to make requests such as 'what should I do?' The future is formed by adding the affix -g- to the subjunctive forms plus the usual gender and number markers.

-

The conjugation of ānā ('to come') in these two tenses is:

-

black: verb root; blue: personal endings; green: future marker; red: gender and number marker.

-

•voice: active and passive. The passive is formed with the simple perfective form of the lexical verb followed by the auxiliary jānā ('to go') which is fully conjugated. Most passive sentences are impersonal, but when the agent is known it is marked with the instrumental postposition se ('by') or with the more formal (ke) dvara. Passive sentences with the auxiliary in the subjunctive are very common because they serve to make requests or offers.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, conjunctive participle (gerund), imperfective and perfective participles.

-

‣The infinitive is formed by adding the suffix -nā to the stem.

-

‣The conjunctive participle or gerund (also known as converb), is used in linked sentences in which two verbs have the same subject, and expresses an action happening before another, functioning frequently as an adverb. It is formed with the verb root plus the marker kar (the root of the verb to do):

-

vah ghar pahũckar bāzār gayā

-

He home reach-kar market went

-

'He went to the market after coming home.'

-

‣Participles are verbal forms that may function as adjectives or adverbs; when used as adverbs they are invariable, but when used adjectivally they agree in gender, number and case with the noun they modify.

-

Perfective participles indicate completed actions and are formed by the addition of the adjectival suffixes -ā, -e or -ī to the verbal stem to mark gender and number agreement with the noun.

-

Imperfective participles indicate incomplete actions and are formed with the addition of the suffixes -tā (masc. sg.), -te (masc. pl.) and -tī (fem. sg. and pl.) to the verbal stem when they act as adjectives, but with the invariable suffix -te when used as adverbs.

Syntax

Word order is Subject-Object-Verb. Sentences show agreement in number, gender, person and case. The indirect object precedes the direct object. Adjectives precede their nouns. Negation particles are placed immediately before the verb. Transitive verbs conjugated in any of the perfective tenses agree with their object while the subject adopts the oblique case, a phenomenon known as split ergativity. The most common words to negate a sentence are nahī̃, mat and na. The first one is most frequently used in declarative sentences. Mat is restricted to some forms of the imperative while na is used in other forms of the imperative, in rhetorical questions and in the construction equivalent to the English 'neither.....nor'.

Yes/no questions are indicated by the interrogative marker kyā placed at the beginning of the sentence. In colloquial Hindi this marker is frequently omitted, and a question is only distinguished by intonation. Information questions are indicated by a variety of interrogative words that appear immediately before the verb. Hindi uses postpositions instead of prepositions.

Lexicon

Most Hindi words descend from Old Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit and putative related languages), having experienced the appropriate sound changes. However, a number of Hindi words that are identical, or very similar, to their Sanskrit counterparts are considered borrowings, promoted by the prestige of the mother language. Other important sources of borrowings have been Persian, Arabic, English, Turkish, and Portuguese, in that order. There are also a number of Dravidian loanwords in Hindi, but most of them have come through Sanskrit. Hindi has also adopted words from other Modern Indo-Aryan languages, such as Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, and Punjabi.

Basic Vocabulary

one: ek

two: do

three: tīn

four: cār

five: pā̃c

six: chaḥ (pronounced che)

seven: sāt

eight: āṭh

nine: nau

ten: das

hundred: sau

father: pitā/piu

mother: mātā/mā/māū

brother: bhāi

sister: bahan/bahin

son: beṭā/putra

daughter: beṭī/dhī/dhiya, putrī

head: sir/sirā

face: ceharā

hand: hāth

eye: ā̃kh

foot: pā̃v

heart: hṛdaya

tongue: jībh

Key Literary Works (for the sake of convenience, Hindi titles are shown without diacritic marks)

-

late 12th c. Prithviraj Raso. Chand Bardai

-

A long epic poem chronicling the life and exploits of king Prithviraj of Ajmer, composed by the court bard.

c. 1200-1300 Dhola Maru. Anonymous

-

A love ballad of Rajasthan, tinged with fantastic events, celebrating the reunion of a princely couple, married when children and afterwards separated.

-

late 15th c. Kabir's Songs. Kabir

-

Critical of both, Hinduism and Islam, Kabir focused in the unity of God beyond rituals and social conventions.

-

16th c. Sursagar (Sur's Ocean). Surdas

-

Devotional poems to Krishna, meant to be sung, describing the loves of the young god with the cow-herder Radha as well as incidents from Krishna's childhood.

-

1574-1577 Ramcaritmanas ([Sacred] Lake of the Acts of Rama). Tulsidas

-

A vernacular version of the Sanskrit epic Ramayana coined in artful verse, expressing an intense love for a personal god.

-

1620-1650 Satasai (Seven Hundred [Verses]). Bihari

-

713 couplets about women and love.

-

1881 Andher Nagari (City of Darkness). Bharatendu Harishcandra

-

Harishcandra was a multifaceted writer (essays, poems, plays) who modernized Hindi literature. Andher Nagari, a political satire, is one of his most famous plays.

-

1900-1936 Mansarovar (The Holy Lake). Premchand

-

The collected short-stories of Premchand (in Hindi and Urdu), picturing a whole range of northern Indian characters entangled in the mesh of an unjust society.

-

1936 Godan (The Gift of a Cow). Premchand

-

The dream of owning a cow leads a peasant to borrow money and to family conflicts and, ultimately, to his ruin and death.

-

1938 Sarojsmriti (In Memory of Saroj). Suryakant Tripathi Nirala

-

A long poem dedicated to his deceased daughter is among the best known works by Nirala whose palette is, however, much larger. A selection of his poems has been translated into English under the title 'A Season on the Earth'.

-

1954 Maila Ancal (The Soiled Border). Phanishwar Nath Renu

-

A social novel describing the troubled lives of villagers in a remote and poor region of Bihar in the 1940s, and the abnegation of a doctor who took care of them.

-

1959-2003 Short Stories. Nirmal Verma

-

Considered one of the founders of the Nai Kahani (new short story), Nirmal Verma deals with introspection, isolation and the search of identity, resorting to Western literary techniques.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-Outline of Hindi Grammar. R. S. McGregor. Oxford University Press (1977).

-A Primer of Modern Standard Hindi. M. C. Shapiro. Motilal Banarsidass (1989).

-Hindi. Y. Kachru. John Benjamins Publishing Co. (2006).

-A House Divided: The Origin and Development of Hindi/Hindavi. A. Rai. Oxford University Press, Delhi (1984).

-Literary Cultures in History. Reconstructions from South Asia. Sheldon Pollock (ed). California University Press (2003).

Hindi

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania