An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Names: Central Khmer, Cambodian.

Classification: Austroasiatic, Mon-Khmer, Khmeric. Khmer is related to, but probably different from, Northern Khmer spoken in northeast Thailand.

Overview. Khmer is the national language of Cambodia and the second largest Austroasiatic language after Vietnamese. In contrast with Vietnamese, Khmer has typical Austroasiatic features like monosyllabic or disyllabic words, a complex vowel system and lack of tones. It is mostly isolating, attaching one or, at most two, affixes per word to achieve some morphological diversity.

Distribution. Khmer is spoken by the majority of the population of Cambodia, as well as in southern Vietnam and eastern Thailand. Many considered the Thailand variety of Khmer as a different, though closely related, language.

Speakers. Khmer is spoken by about 15 million people of which 14 million in Cambodia and one million in Vietnam.

Status. Khmer is the official language of Cambodia.

Varieties. Besides Standard Khmer spoken in Cambodia, the main dialects are Lower Khmer in Vietnam and Northern Khmer in Thailand (usually regarded as a different language).

Periods

7th-14th c. Old Khmer. Attested by inscriptions in stone.

15th-19th c. Middle Khmer. Represented by inscriptions and manuscripts. Coincides with the spread of Theravada Buddhism and the consequent adoption of many Pali loanwords.

19th c.-present. Modern Khmer

Oldest Document. The oldest record of the language is a stone inscription in Old Khmer dating from 611 CE found at Angkor Borei, part of the kingdom of Chenla at the time. Contemporaneous or even older Sanskrit inscriptions exist in Cambodia. Sanskrit and Khmer were both used for writing by the Khmer elites until the arrival of Buddhism.

Phonology

Word structure: Khmer words can be monosyllabic or disyllabic. In a disyllabic word a major syllable is preceded by a minor unstressed 'half-syllable'. The range of vowels of the minor syllable is severely restricted. Khmer allows consonant clusters in initial position, particularly of a stop followed by a sonorant (a glide, a liquid or a nasal consonant) or of a stop followed by h.

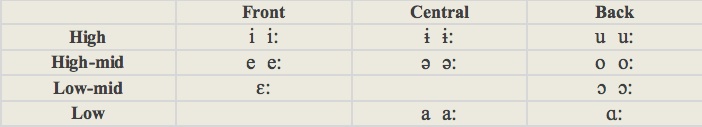

Vowels (18): Austroasiatic languages are remarkable for having large vowel inventories and Khmer is no exception. It has at least 18 monophthongs with four degrees of vowel height which can be short or long, in addition to several diphthongs. In Old Khmer there was, besides, a register distinction, between breathy, creaky or clear voice, that no longer exists. There is no complete agreement about the Khmer vowel system, a tentative description is the following:

-

a) Monophthongs

-

b) Diphthongs: iə, ɨə, eə, ei, əw, aɛ, aə, aj, a:o, ou, ue, ɔe

Consonants (21): Khmer labial and dental stops exhibit a three-way contrast between voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated and voiced. In contrast, the palatal affricates and velar stops contrast only between voiceless unaspirated and aspirated.

Script and Orthography

The Khmer script is one of the oldest of mainland Southeast Asia. It derives from a South Indian alphabet, employed by the Pallava dynasty, which itself derives ultimately from the Brāhmī script of northern India.

The Khmer script is an abugida or alphasyllabary i.e. every consonant has an inherent vowel which can be [a] or [ɔ]. Alphabetic order mimics that of its Indian model, which was based on phonetic principles. The alphabet begins with the simple vowels, followed by the syllabic ones, and the diphthongs. Afterwards, we find the consonants grouped according to place and manner of articulation. Between the palatal and dental stops there was a retroflex series in the Indian original script which is pronounced as dental in Khmer.

There is no agreed transliteration system. One of them is shown here below the Khmer characters; the International Phonetic Alphabet equivalents are shown between brackets. As the Khmer script doesn’t represent accurately the complex phonology of the language, we use in this page, a phonetic transcription to avoid ambiguities.

Morphology

Khmer words do not present inflections of any kind. Nouns are not marked for case, gender, or number, and there are no articles. Equally, the verb is not inflected for tense, aspect, mood or person.

-

a)Nouns

-

•number: may be inferred from context, by using a numeral or words like 'some' or 'all', or by duplicating the world: cru:k ('pig') cah ('old') cah ('old') = old pigs.

-

•gender: may be inferred from context or by adding words like 'male' or 'female'.

-

•possession: may be expressed by simply placing side by side the possessed and the possessor (in that order) or by forming a compound word.

-

•noun classifiers: in contrast with Vietnamese, classifiers are few in Khmer and used mainly for counting persons (neak), animals and books (kba:l) as well as houses (knaw:ŋ); awŋ is used for monks, images of the Buddha and royalty.

-

b)Pronouns

-

For the second person there is a variety of pronouns and kinship terms marking several degrees of politeness, familiarity and relative social position.

-

Neutral, all-purpose personal pronouns are:

-

khnhom (1st person)

-

lo:k (2nd person male)

-

lo:ksrəj (2nd person female)

-

koət (3rd person).

-

Plural forms are made by adding teəng.'ah.

-

Demonstratives distinguish proximal and distal: nih (‘this, these’), nuh (‘that, those’). The interrogatives are neə.na: (‘who?’) and wəj (‘what?’). The relative pronoun dael follows the head-word.

-

c)Verbs

-

Prefixation, infixation, auxiliary particles and reduplication are employed to express aspect, mood, voice, etc. A word may have either a prefix or infix, but not both. Khmer has no suffixes. For example, the prefix p-/ph- produces causatives, the prefix prɔ- indicates reciprocity, the infix -ɔm- transforms an intransitive verb into a transitive one, the infix -m- serves to derive a noun from a verb. Partial reduplication of the verb expresses intensiveness or reiteration. Mood and aspect are usually conveyed by postverbal particles, like haəy (perfective aspect), kɔmpung.tae (imperfective aspect), craən.tae (habitual action), trəw (obligation), cɔng (wish or design).

Syntax

Khmer basic word order is Subject-Verb-Object (SVO). Noun and verb modifiers follow the noun and the verb, respectively. Prepositions and word order indicate syntactical relations. A variety of particles is used at the end of sentences to express familiarity or respect as well as the intentions of the speaker. Serial verb constructions (two or more adjacent verbs sharing the same subject) might express a temporal sequence or the direction, objective, manner, means or result of an action.

Lexicon

As a consequence of the Indianization of ancient Cambodia and the impact of Hinduism and Buddhism, Khmer has adopted many loanwords from Sanskrit and Pali, especially in the religious, administrative and cultural domains. Thai and Khmer have been influenced by each other and, as a result, lexical borrowings have occurred both ways.

Basic Vocabulary

Key Literary Works

16-17th c. Ramakerty. Anonymous

-

The Ramakerti, also known as Reamker, is a Khmer version of the Ramayana, the Sanskrit epic that was, and still is, so popular in all Southeast Asia. It is composed of songs to be chanted as accompaniment of a dance performance. It differs in many respects from the original Indian version, showing Buddhist influence and an indebtedness to the Javanese version of the same story.

-

1620 Lpoek Angar Vatt (The Poem of Angkor Vat). Anonymous

-

Prince Ketumala had been a son of god Indra in a previous existence. Indra sends his architect to build the temple-palace of Angkor Vat for Ketumala. The poem celebrates this superb temple and describes the bas-reliefs in its galleries that recount episodes of the Ramayana.

-

19th c. Tum Teav (Tum and Teav). Santhor Mok and others

-

It is a tragic love story, believed to be based on real events, transmitted orally until it was recorded in the 19th century by the poet Santhor Mok. Tum, a novice Buddhist monk, falls in love with beautiful Teav, who reciprocates his feelings. Her mother, unawares, arranges the marriage of Teav with the governor of her province and the conflict between individual rights and social obligations turns violent ending with the death of Tum and Teav.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Khmer'. M. Minegishi. In Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, 597-600. K. Brown & S. Ogilvie (eds). Elsevier (2009).

-

-The Languages of East and Southeast Asia: An Introduction. C. Goddard. Oxford University Press (2005).

-

-An Introduction to Cambodian. J. M. Jacob. Oxford University Press (1968).

-

-Modern Spoken Cambodian. F. E. Huffman. Yale University Press (1970).

-

-Cambodian: Khmer. J. Haiman. London Oriental and African Language Library. John Benjamins (2011).

Khmer

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania