An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Names: Kirgiz, Kyrgyz.

Classification: Altaic?, Turkic, Northwestern (Kipchak) branch, South group.

Kirghiz is a member of the Turkic family. The external classification of Turkic is disputed. Many consider it one of the three divisions of the Altaic phylum but for others its relationship with Tungusic and Mongolic is not proven. Kirghiz belongs to the southern group of the Kipchak branch along with Kazakh, Karakalpak, Kipchak Uzbek, and Nogai.

Overview. Modern Kirghiz might be a descendant of the language spoken by the ancient Kirghiz who founded a steppe empire in 840 that lasted nearly a century. However, the relationship between Old and Modern Kirghiz is not certain and a matter of dispute. Later, the Kirghiz were subject to other peoples and migrated many times, their language being modeled by a variety of influences, especially by Mongolic, Kazakh, Uzbek and Russian. However, Kirghiz remains a typical Turkic language with agglutinative morphology based on suffixes, verb-final syntax and vowel harmony.

Distribution. Kirghiz is spoken mainly in Kyrgyzstan and bordering regions of Uzbekistan (Ferghana valley) and China (Xinjiang Autonomous Region). Fewer speakers are found in Tajikistan, Kazakhstan and Russia.

Speakers. According to the 2009 national census of Kyrgyzstan, close to 71% of the total population speak Kirghiz (14.3 % speak Uzbek, and 7.8 % Russian). There are about 4.4 million Kirghiz native speakers in the following countries:

Kyrgyzstan

Uzbekistan

China

Tajikistan

Russia

Kazakhstan

3,900,000

180,000

160,000

65,000

32,000

10,000

Status. Kirghiz is, together with Russian, an official language of Kyrgyzstan since 1989. The proportion of Kirghiz speakers in Kyrgyzstan has increased significantly in the last two decades as shown by the 1989 and 2009 national censuses, reaching now more than 70 % of the population of the country. In contrast, the number of native speakers of Russian has decreased dramatically though it still remains the most widely spoken second language and a vehicle for interethnic communication.

Varieties

-

a)Southern group which includes dialects, influenced by Uzbek, spoken mainly in the Ferghana basin.

-

b)Northern group which includes dialects less influenced by Islamic vocabulary; the literary language is based on them.

-

c)There is a specific variety of Kirghiz in Xinjiang (China) distinguished by its many Chinese loanwords.

Oldest Document. It is the Epic of Manas transmitted first orally and later written down for the first time in the 19th century.

Phonology

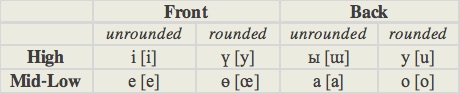

Vowels (14): Modern Kirghiz has 8 short and six long vowels. The short vowels conform a symmetrical system regarding height (4 high and 4 mid-low vowels), backness (4 front and four back), and roundness (4 unrounded and 4 rounded):

The symbols are those current in writing in the Cyrillic alphabet; those of the International Phonetic Alphabet are indicated between brackets. Their usual transliteration in the Latin alphabet is as follows:

-

i [i] is transliterated i.

-

ү [y] is transliterated ü.

-

ы [ɯ] is transliterated ï.

-

a [a] is transliterated a.

-

e [e] is transliterated e.

-

ɵ [œ] is transliterated ö.

-

у [u] is transliterated u.

-

o [o] is transliterated o.

Kirghiz long vowels, [e:], [y:], [œ:], [a:], [u:], [o:] are not inherited from Proto-Turkic long vowels (like in Turkmen), but are the product of consonant loss in native words and of diphthongs in borrowed words. They have a more limited occurrence than short vowels and are represented by duplicated characters in written Kirghiz and by a macron in transliteration (ā, ō, etc).

Vowel harmony. Kirghiz, like other Turkic languages, exhibits vowel harmony. It governs the distribution of vowels within a word opposing front versus back vowels. In the first syllable of a word all vowels can occur. If it is a front vowel all the subsequent vowels must be also of the front type. If it is a back vowel all the other vowels must be also of the back type. Thus, all the vowels of a word belong to the same class (back or front) and the vowels of suffixes vary according to the class of vowels in the primary stem. Another type of vowel harmony is based on roundness.

However, in Kirghiz this phonetic process has many asymmetries.

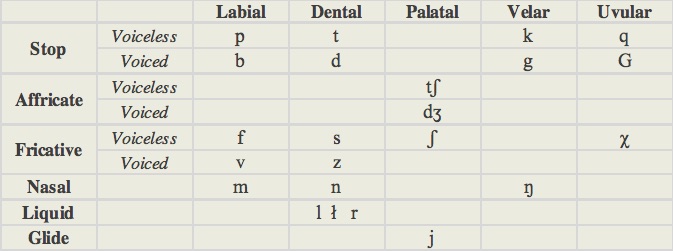

Consonants (23):

k, g and l have front and back variants which are realized in a front vowel or back vowel environment as:

-

k → q (uvular)

-

g → G (uvular)

-

l → ł (velarized)

Stress: falls usually on the last syllable.

Script and Orthography

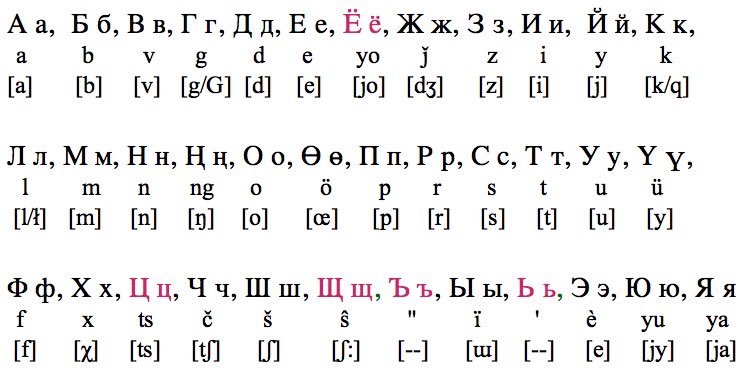

Kirghiz was initially written in the Arabic script, but in 1928 it was replaced by the Latin alphabet. The latter, in turn, was abandoned in favor of Cyrillic in 1941. The Arabic script is still used to write Kirghiz in China. The Cyrillic Kirghiz script has 36 letters (below each one, its equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown):

There is no standard transliteration of Kirghiz into the Latin alphabet. We have mostly followed M. Kirchner (1998) but we replaced χ for x.

-

The letters highlighted in color are used only in foreign words.

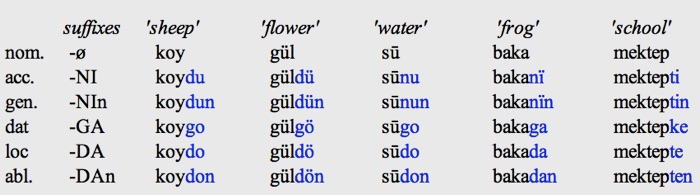

Suffixes variants. Due to sound harmony all vowels and some consonants of suffixes change according to the preceding sounds. This is indicated with capital letters as follows:

-

A indicates a low vowel that is realized as e [e] after a front unrounded vowel, as ö [œ] after a front rounded vowel, as a [a] after a back unrounded vowel or as o after a back rounded vowel.

-

I indicates a high vowel that is realized as i [i] after a front unrounded vowel, as ü after a front rounded vowel, as ï [ɯ] after a back unrounded vowel or as u [u]after a back rounded vowel.

-

D may be realized as d, or t. N may be realized as n, t, or d. L may be realized as l, t or d.

-

K may be realized as [k] or [q], G as [g] or [G] and l as [l] or [ł] but in these three cases the change is not recognized in the Kirghiz script.

Morphology. Kirghiz is an agglutinative language adding different suffixes to a primary stem to mark a number of grammatical functions. Each morpheme expresses only one of them and is clearly identifiable.

-

Nominal. Suffixes are added to nominal stems to indicate number, possession and case (in that order).

-

•gender: there is no grammatical gender.

-

•number: singular and plural. The singular is unmarked and the plural is marked with the suffix -LAr. For example: tȫ ('camel'), tȫlör ('camels'). Nouns used in a collective sense are not marked for plurality.

-

•possession: there are six possessive markers, one for each person and number, that are attached to the noun after the plural marker and before case suffixes:

-

1s-(I)m

-

2s -(I)ŋ

-

3s-(s)I

-

1p -(I)bIz

-

2p-(I)ŋAr

-

3p-LArI

-

•case: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, locative, ablative. The nominative is unmarked; the other cases are marked by suffixes, which are subject to vowel and consonant harmony, attached to the noun stem in the third position.

-

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, reflexive, interrogative.

-

Personal and demonstrative pronouns decline in six cases like nouns, with minor differences. The personal pronouns are:

-

The 2nd plural has other forms:

-

siz and sizder are polite forms for one addressee and more than one addressee, respectively.

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish four deictic degrees: bu ('this', visible), ošo ('this', invisible), al ('that', visible) and tigi ('that', invisible).

-

The reflexive pronoun öz is attached to a possessive suffix. The interrogative pronouns are emne ('what?'), kim ('who?'), kaysï ('which?').

-

Verbal

-

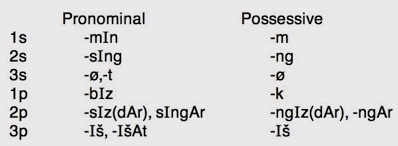

A finite verb form has a verbal stem + tense-aspect or mood marker suffixes + personal markers (possessives or pronominals). The possessive-based personal markers are used in the simple past and the conditional, those of pronominal origin elsewhere.

-

Negation is done by adding -BA after the stem.

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p.

-

•tense: simple present, progressive present, simple past, perfect past, indirective past, prospective (future).

-

The simple present is formed with the suffix -A plus pronominal personal markers, the progressive present with the suffix -(I)p plus present forms of ǰat ('lie') or otur ('sit)', plus pronominal personal markers:

-

ište-p otur-mun

-

work-PPROG AUX-1st. sg

-

'I am working'.

-

The simple past is formed with the suffix -DI plus possessive personal markers. The perfect past uses the suffix -GAn and the indirective past the suffix -(I)ptIr; in both cases with pronominal personal markers. The prospective is formed with the suffix -(A)r.

-

An imperfect tense is made by combination with the past copula particle ele. Constructions with the same particle can express counterfactual notions.

-

•aspect: imperfective, perfective, habitual.

-

•voice: active, reflexive, passive, cooperative-reciprocal, causative.

-

•mood: indicative, optative-imperative, conditional. The optative-imperative has its own personal markers.

-

•non-finite forms: verbal nouns, participles (-gan, durative, aorist), converbs.

-

Participles and converbs convey many shades of temporal, aspective, and modal notions. The aorist participle has a prospective or future sense.

Syntax

Kirghiz, like all Turkic languages, has a basic Subject-Object-Verb word order which, nevertheless, can be changed to highlight a certain topic. It is head final, modifiers preceding their head. It employs postpositions (corresponding to English prepositions, but placed after the words they interact with) to specify and precise syntactical relations established by the grammatical cases. Plural agreement between subject and predicate is observed more often than in other Turkic languages. Conjunctions are few and their use is limited. Relative clauses and complements are left-branching, and converbs ending in -(I)p are used for chaining clauses.

Lexicon

The basis of the Kirghiz lexicon is of Kipchak Turkic origin. Among loanwords, many come from Mongolic due to prolonged nomadic contacts. Arabic and Persian loanwords entered Kirghiz through Chaghatay and Uzbek as a consequence of Islamization; they are more abundant in the southern dialects. Later, many Russian terms were adopted but recently an effort has been made to reduce their number. The Kirghiz spoken in Xinjiang includes many Chinese loanwords.

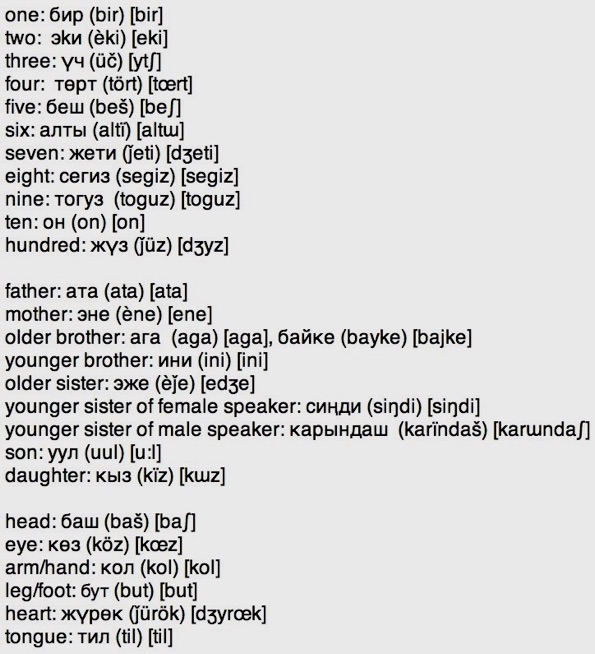

Basic Vocabulary (in Cyrillic script with transliteration (between brackets) and phonetic transcription (between square brackets).

Key Literary Works

16th-20th c. Manas. Anonymous

-

A very long epic cycle, with over 500,000 lines in verse, whose hero is the legendary Manas, a defender of the Kirghiz lands against powerful invaders. After the death of Manas, the epic continues with the adventures of his son Semetei and grandson Seitek. It was sung by the manaschi from memory, adding their own improvisations, in performances that could last several days. Transmitted orally during many generations, it was finally started to be compiled in written form in the 19th century. Besides its narrative core, it constitutes a sort of encyclopedia of Kirghiz customs, religion, history and geography. It is impossible to date the epic but Manas, who is not a historical figure, is first mentioned in a Persian manuscript of the 16th century.

-

1958 Jamila. Chingiz Aytmatov

-

The story of a peasant woman who betrays the husband chosen by her extended family, who is fighting in the front, with a disabled war veteran and abandons him. In contrast with the stereotypes current in Soviet literature, she chooses personal happiness over her social obligations. Aytmatov wrote other important works directly in Russian, like "Farewell Gul'sary" and "The Day Lasts more than a Hundred Years" (see Russian literature).

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Kirghiz'. M. Kirchner. In The Turkic Languages, 345-356. L. Johanson & É. Á. Csató (eds). Routledge (1998).

-

-Kirghiz Manual. R. J. Hebert & N. Poppe. Indiana University (1963).

-

-Le Kirghiz (2 vols). G. Imart. Université de Provence (1981).

Kirghiz

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania