An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Names: Middle Persian, Sassanian Pahlavi.

Classification. Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Middle Iranian, Western. Pahlavi is closely related to Parthian.

Overview. Pahlavi is the prototypical Middle Iranian language, employed under the Sassanians for government, trade and literature which includes many Zoroastrian religious texts. Middle Persian is descended from Old Persian and is the ancestor of Modern Persian.

Distribution. Originally from southwestern Iran (Fars province), it later expanded into the vast territories of the Sassanian empire (224-651 CE).

Status. Extinct. Pahlavi was in use from the 3rd century BCE until the 10th century CE. Its heyday was between the 3rd and 7th centuries CE, coinciding with the existence of the Sassanian empire.

Varieties. Inscriptional Pahlavi, Book Pahlavi and Manichean Middle Persian. Inscriptional Pahlavi is the language of early inscriptions. Book Pahlavi was used in Zoroastrian writings, and Manichean Middle Persian was used in Manichean texts.

Main Documents

-

•Rock inscriptions and coins from the beginning of the Parthian period.

-

•A substantial corpus of Zoroastrian scriptures.

-

•Sassanian official inscriptions and documents.

-

•A translation of the Psalms of David found in Turfan (Xinjiang, China).

-

•Manichean texts from Turfan.

Phonology

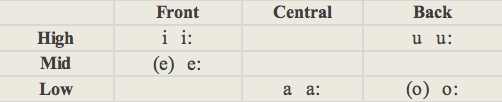

Vowels (8-10). As the Pahlavi script didn't note appropriately the vowels, there are some doubts about the status of two of them (between brackets).

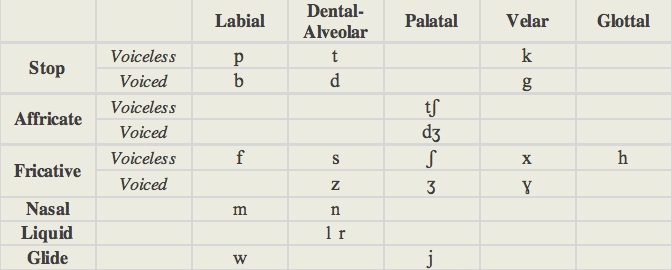

Consonants (22). Pahlavi consonants were articulated at four main places, being classified as labial, dental-alveolar, palatal and velar. Its stops, affricates and numerous fricatives have all (except f and h) contrasting voiceless and voiced varieties.

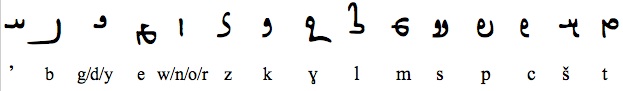

Scripts. Pahlavi was written with a script based on the Aramaic cursive script. Like it, it lacked notation for vowels and was read from right to left. It had only 15 letters and many ambiguities. A number of Aramaic-based logograms were used to write certain verbs and words. Here, we show the Pahlavi script (from left to right for the sake of clarity) with the usual transliteration below each character.

Long vowels are transcribed with a macron (ī, ā, etc). The affricates [tʃ] and [dʒ] with č and ǰ, respectively. The fricatives [ʃ] and [ʒ] with š and ž, respectively. [j] is rendered as y.

Morphology. In contrast with the elaborate case and verbal systems of Old Iranian, Middle Iranian morphology was drastically simplified.

-

Nominal

-

•gender: no distinctions between genders are made.

-

•number: singular, plural (the dual of Old Iranian disappeared). General plurality is indicated by the suffix -ān. Another suffix, -ihā, was employed to emphasize individual plurality, e.g. kōfān 'the mountains', kōfihā 'the individual mountains'.

-

•case: In the early stages of Middle Iranian traces remain of only two cases, direct (derived from nominative) and oblique (derived from genitive), but they vanish soon. Most of the nominal stems resemble the old oblique case without the suffix marker but some are like the old nominative. Pronouns experienced a similar, radical, inflectional simplification.

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive (rare), reflexive, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

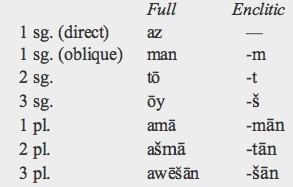

Personal pronouns have full and enclitic forms. Full forms are only inflected for case (direct and oblique) in the 1st person singular. The enclitics are only used as oblique (never as subject).

-

Note: some scholars consider that the 1st singular direct pronoun should be read an.

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish near and far. Some forms are identical to the 3rd person pronouns while others are different: im ('this'), ēd ('this'), ēn ('this'), ōy ('that'), ān ('that'). Only im and ōy have plurals which are, respectively, imēšān ('these') and awēšān ('those).

-

Interrogative pronouns function as indefinite pronouns when doubled or in combination with demonstratives, e.g. kē ('who?'), čē ('what?'), kēkē ('someone'). Interrogative adverbs are: kū ('where?'), kay ('when?'), čiyōn ('why?'), čim ('why?').

-

-

Verbal. Conjugation is based upon the present and past stems of the verb. From the present stem are made the present of the indicative, subjunctive, optative, and imperative. From the past stem are made the preterite and perfect tenses of the indicative, subjunctive and optative.

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p. The dual of Old Iranian no longer exits in Pahlavi.

-

•tense: present, preterite, pluperfect, present perfect, past perfect.

-

The three past tenses of Old Iranian (imperfect, aorist and perfect) disappeared altogether being replaced by periphrastic constructions combining the past stem with an auxiliary verb: either būdan ('to be') or estādan ('to stand').

-

The present of the indicative is formed with the present stem + present endings; it is used to express present and future actions.

-

The preterite is formed with the past stem + present of 'to be'.

-

The pluperfect with the past stem + preterite of 'to be'.

-

The present perfect with the past stem + present of 'to stand'.

-

The past perfect with the past stem + preterite of 'to stand'.

-

-

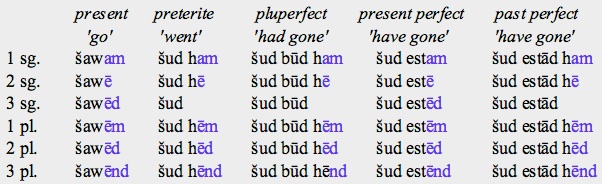

We show below the conjugation of the verb šudan ('to go'):

-

The preterite is the general past tense.

-

The pluperfect is used to indicate that an action was completed before another. The present perfect and past perfect express a state resulting from a previous event.

-

•mood: indicative, imperative, subjunctive, optative.

-

The last two were sparingly used and only with certain persons. The imperative has zero ending in the 2nd singular, and is identical with the present indicative in the 1st and 2nd plural.

-

•voice: active, passive.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, present participle, past participle, gerundive.

-

Infinitives have two forms: a short one identical to the past participle and a long one formed by adding -an to the past stem e.g kerdan ('to do'), griftan ('to take'), madan ('to come'), estādan ('to stand').

Syntax

Due to the loss of the Old Iranian case system, word order became less free. The normal, unemphatic, order is Subject-Indirect Object-Direct Object-Verb. Agreement between adjectives and nouns became less strict, paralleling the collapse of the case system. Syntactical relations are determined by word order and a by variety of adpositions (prepositions, postpositions or circumpositions). Ergative constructions are attested.

Lexicon

Pahlavi has a few loanwords from Sanskrit, Greek and Aramaic.

Basic Vocabulary

one: ēk

two: dō

three: sē

four: čahār

five: panǰ

six: šaš

seven: haft

eight: hašt

nine: nō

ten: dah

hundred: sad

father: pid, pidar

mother: mād, mādar

brother: brād, brādar

sister: xwah, xwahar

son: pus, pusar

daughter: duxt, duxtar

head: sar

face: čihr, rōy

eye: čašm

hand: dast

foot: pay, pāy

heart: dil

tongue: uzwān

Literature.

-

300-600 Ayadgar i Zareran (Memorial of Zarer)

-

One of the few surviving secular works, it is a Sassanian epic poem based on an older Parthian version. It describes the battle between Wištasp, converted to the Zoroastrian faith, and his challenger Arjasp. Zarer, the brother of Wištasp is treacherously killed and his son laments his death.

-

500-600 Zand-i Wahman Yast

-

An eschatological and apocalyptical work in which Ahura Mazda (the supreme god) gives Zarathustra a prophetic account of the fate of the Zoroastrians and their religion.

-

500-700 Bundahisn (Primal Creation)

-

A cosmology and cosmogony based on the Zoroastrian scriptures. It exists in two recensions: a larger Iranian version and a smaller, more corrupt, Indian one.

-

600-650 Madayani Hazar Dadestan (Book of a Thousand Judgements)

-

In stark contrast to other Pahlavi works, this one has no religious content at all, being concerned exclusively with legal matters. It is the only one of its kind that has survived from pre-Islamic Iran.

-

600-650 Kārnāmak-i Ardeshi-i Pāpakān (Book of Deeds of Ardashir)

-

An epic tale in prose narrating the legendary adventures of the founder of the Sassanian dynasty.

-

800-900 Dadestan-i Denig (Religious Decisions)

-

Written by the high priest Manuschir, it contains 92 questions posed to Manuschir and his answers. Their subjects are varied ranging from the religious to the legal, from the ethical to the social.

-

c. 881 Epistles of Manuschir

-

This second work by the priest Manuschir is concerned with ritualistic matters. It consists of epistles addressed to the community of Sirjan, to his brother Zadspram, and to the Zoroastrian faithful at large.

-

800-900 Wizidagiha i Zadspram (Selections of Zadspram)

-

A work by the scholar and theologian Zadspram, brother of Manuschir, containing an account of the creation of the world, legends about Zarathustra's life, his personal views on the nature of the human person and, finally, an eschatology.

-

800-900 Skand Gumanig Wizar (Final Dispelling of Doubts)

-

Written by Mandarfarrox, it expounds the basic tenets of Zoroastrianism while polemicizing against the four monotheistic religions: Manicheism, Christianity, Judaism and Islam.

-

800-900 Arda Wiraz Namag (The Book of Wiraz the Just)

-

Describes Wiraz's soul voyage to heaven and hell, and the pleasures and pains awaiting the virtuous and the wicked.

900-1000 Denkard (Acts of the Religion)

-

Part encyclopedia, part compilation, part justification of the Zoroastrian faith vis-à-vis Islam.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Pahlavi'. M. Hale. In Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas, 123-135. R. D. Woodward (ed). Cambridge University Press (2008).

-

-'Middle West Iranian'. P. O. Skjærvø. In The Iranian Languages, 196-278. G. Windfuhr (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-Pahlavi Primer. P. O. Skjærvø (2007). Available online at:

-

-A Manual of Pahlavi (2 vols). H. Nyberg. Otto Harrassowitz (1964).

-

-Die Mittelpersische Sprache und Literatur der Zarathustrier. J. Tavadia. Otto Harrassowitz (1956).

-

-'Middle Persian Literature'. M. Boyce. In Handbuch der Orientalistik 4.2.1. Iranistik Literatur, 32-65. B. Spuler (ed). Brill (1968).

Pahlavi

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania