An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Names: Quichua.

Overview and Classification. Quechua is a native South American macro-language or dialect continuum with no proven external relatives. It has some similarities with Aymaran languages which, most probably, are due to close contact. It is the largest indigenous language of South America with around eight million speakers.

The Quechua homeland was in the Andean and coastal regions of central Peru since the end of the first millennium CE. In the 15th century it was adopted as the language of administration by the rulers of the Inca empire spreading beyond the boundaries of Peru. Later, it was used by the Spanish colonizers as a sort of lingua franca among the indigenous peoples of the Andes, in detriment of local languages, spreading even further. At the end of the 18th century the Spanish rulers engaged in a long period of repression that initiated the decline of Quechua.

Like all South Amerindian languages it was not written before the Spanish conquest. It has a relatively simple sound system and an agglutinative morphology employing suffixes added to nouns and verbs to mark grammatical features.

Distribution. Quechua is spoken in the central Andean region, from southern Colombia to north-western Argentina, particularly in Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia. In Colombia, in the departments of Caquetá and Nariño; in Ecuador, in the Highlands and Eastern Lowlands; in Peru, across the entire Andean region; in Bolivia in the departments of Cochabamba and Potosí and around the city of Sucre; in Argentina in the provinces of Santiago del Estero and Jujuy (plus many emigrants in the city of Buenos Aires). The Quechua language area is interrupted by large Aymara-speaking and Spanish-speaking regions.

Speakers. Around 7-8 million people in the following countries: Peru (3,300,000), Bolivia (1,800,000), Ecuador (1,500,000), Argentina (900,000), Colombia (23,000).

Status. For a long time, Quechua has been slowly losing ground to Spanish which is the language of government and education. However, in 1975 Quechua was recognized as second national language in Peru, and in the Bolivian constitution of 2009 thirty-four indigenous languages (Quechua included), were recognized as official along with Spanish. In Ecuador Quechua is an official language for the indigenous peoples.

Varieties. Quechua has many dialects with limited degree of mutual intelligibility constituting a sort of ‘dialect chain’. They can be divided into Quechua I and Quechua II groups which separated early from the protolanguage. Quechua I or Central Peruvian Quechua is spoken in the Andes of Central and Northern Peru. Quechua II dialects are located to the north and south of Quechua I, being spoken in northern and southern Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia and Argentina.

Oldest Documents

In 1560 the first grammar of Quechua was written by Domingo de Santo Tomás. Other early texts include collections of hymns by Cristóbal de Molina (1574), texts by Guaman Poma de Ayala (1615), and a Quechua catechism by Juardo Palomino.

Phonology

Syllable structure: in non-initial syllables is CV(C) and in word-initial syllables (C)V(C). Sequences of consonants within a syllable and word finally are not allowed.

Vowels. Proto-Quechua had just three vowels: back u, central a, and front i. There was no length distinction or it was of marginal importance. The vowels i and u were lowered, respectively, to e, o when adjacent to the uvular consonant q.

In Modern Quechua dialects, due to contact with Spanish, mid vowels, e and o, have been introduced, and now the vowel inventory consists of five vowels in many dialects, except for those that do not have uvulars.

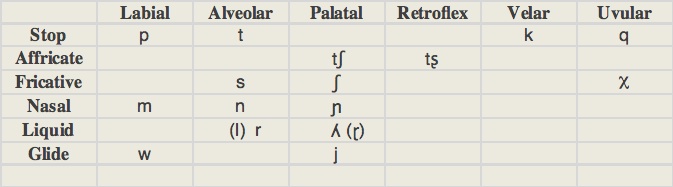

Consonants:

-

1) In Proto-Quechua all stops, affricates and fricatives were voiceless. The back fricative is interpreted as velar, uvular or glottal by different authors.

-

2)In Modern Quechua dialects, like in Proto-Quechua, stops are generally voiceless and in most of them there is a contrast between velar [k] and uvular [q] stops. However, in some Quechua II dialects [k] and [q] have merged into k, and in Quechua I [q] became a fricative or a glottal stop. The distinction between palatal and retroflex affricates is preserved in some, but not all, dialects.

-

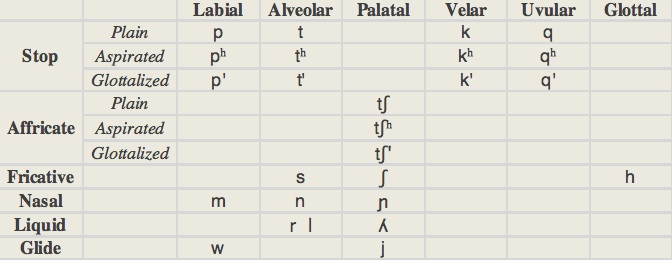

In Cuzco, Puno and Bolivian dialects (spoken near the Aymara area) there are aspirated and glottalized stops. In Ecuador dialects there are also aspirated stops.

-

Cuzco Quechua has 26 consonants:

Stress. In most dialects, it falls on the penultimate syllable.

Script and Orthography. Quechua is written with a Latin-based alphabet. The number of letters varies in different dialects. Most use letters of the Spanish alphabet to which additional characters are eventually added (equivalences in the International Phonetic Alphabetic are shown between brackets).

Morphology

Quechua is an agglutinating language with complex but regular morphology based on suffixation. Words may add several suffixes in a row. Derivational morphology is remarkably rich but compounds are very rare.

-

Nominal. Nouns are marked for number, case and possession but not for gender. Adjectives precede the noun and are invariable.

-

•number: plural may be marked on nouns with the suffix -kuna, but it is optional. It is placed after the noun and before the case marker.

-

•case: nominative, accusative, genitive, allative, ablative, locative, instrumental.

-

Quechua is a nominative-accusative language. Case relations are marked by special suffixes which are attached at the end of the noun phrase. These markers may have different roles in different contexts.

-

The nominative is unmarked, the accusative marker is usually -ta and the genitive one -pa, the allative (motion towards a goal) is marked by -man while -manta is the most common suffix to mark the ablative. The locative marker is -pi in most Quechua II dialects and that of the instrumental is -wan. The case suffix is placed after the plural marker if there is one. As an example, the declension of wasi ('house') is shown in the table.

-

•possession: is indicated by possesive markers attached to the possessed object. They distinguish, three persons, two numbers, and between inclusive and exclusive 1st person plural.

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

Personal pronouns distinguish 1st, 2nd and 3rd persons, singular and plural. The first-person plural may be inclusive or exclusive. They are declined like nouns. In the Cuzco dialect they are: ñoqa (1s), qan (2s), pay (3s), ñoqanchis (1p inclusive), ñoqayku (1p exclusive), qankuna (2p), paykuna (3pl).

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish three degrees of removal: kay is 'this', chay 'that', and chhaqay/haqay that' (yonder).

-

The interrogative pronouns are: pitaq ('who?'), and imataq ('what?'). Yes-no questions can be expressed by the enclitic interrogative particle -chu.

-

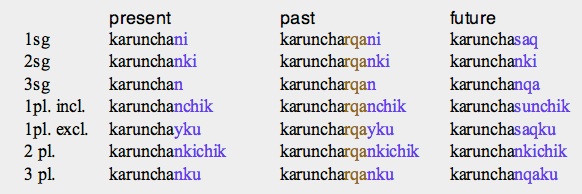

Verbal. All verbal roots end in a vowel, are regular and are conjugated in the same way. They must be followed by at least one suffix marking person and number; tense, aspect and mood markers are optional. Tense and aspect markers are placed after the root and before the personal endings; the conditional mood marker is placed at the end of the verbal complex. The object, direct or indirect, may also be indicated except in the 3rd person; it is placed immediately after the root.

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p inclusive, 1p exclusive, 2p, 3p.

-

•tense: present, past, future.

-

Only the past has a tense marker (rqa). The present and the future lack tense markers but they are differentiated because of the specific personal endings of the future. A progressive tense is expressed by the aspect marker chka. Additionally, most Quechua dialects have one or two compound tenses formed with the auxiliary verb ka (‘to be’). The conjugation of karuncha ('go away') is:

-

brown: past tense marker; blue: personal endings.

-

•mood: indicative, conditional, imperative.

-

The indicative has up to seven tenses, the conditional two and the imperative makes no tense distinctions. The conditional suffix is -man. The present conditional indicates the possibility of an event in the near future while the past conditional refers to an event that has failed to take place in the past. The latter is formed with the aid of the third-person past-tense form of the verb ‘to be’. The imperative has its own personal endings: -y (singular), -ychik (plural).

-

•derivative conjugations: causative, applicative, reflexive, reciprocal, desiderative.

-

New meanings can be added to the verbal root by derivational suffixes placed after it and before tense/aspect markers and personal endings.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, gerunds.

-

The infinitive adds -y to the stem (karunchay = to go away).

Syntax

In full sentences, verb-final order (Subject-Object-Verb) is preferred, but word order is basically free. In dependent clauses verb-final order is obligatory. Quechua is a head-final language i.e., in noun phrases all modifiers precede their heads. Syntactical relations are indicated mainly by the case system and by postpositions. Subordinate clauses precede the main one and subordinated verbs are marked to indicate if the subject of the subordinate clause is the same as that of the main clause. Interrogation, negation, inclusion, completion, emphasis, etc. are indicated by suffixes or enclitics.

Lexicon

Quechua has many loanwords from Spanish which have enriched the vocabulary rather than replaced native terms. The number of native roots in some domains of Quechua vocabulary is quite small but they can have a wide spectrum of meanings. Abstract terms are seldom used. The richness of the derivational morphology contributes to achieve precision of expression.

Basic Vocabulary

one: huk

two: iskay

three: kimsa

four: tawa

five: pichqa

six: soqta/suqta

seven: qanchis

eight: pusaq

nine: isqon/isqun

ten: chunka

hundred: pachak

father: tayta/papa

mother: mama

brother: tura (of a woman)/wawqi (of a man)

sister: ñaña (of a woman)/pana (of a man)

son: wawa (of a woman)/churi (of a man)

daughter: warmi wawa (of a woman)/ususi and warmi churi (of a man)

head: uma

eye: ñawi

foot: chaki

heart: sonqo/sunqu

tongue: qallo/qallu

Literary Works

-

1598 The Huarochirí manuscript

-

Describes the mythology, rituals and celebrations in the valley of Huarochirí. It is the longest text of the colonial period, written by local literate Indians for the parish priest Francisco de Avila who used it as a means to eradicate native cults.

-

16th c. The Death of Atahuallpa

-

An anonymous drama, transmitted orally for four centuries, telling the tragic death of the last Inca king in 1533 at the hands of the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro.

-

18th c. Ollantay

-

A theatre play treating of the love between Ollantay, an Inca general of humble origin, and the Inca princess Cusi Coyllur It is formally European but is based on an Inca legend.

-

1987 Urqukunapa yawarnin (The Blood of the Hills)

-

One of the largest anthologies of Quechua song texts compiled by Montoya et al.

-

1962-72 Quechua poems.

-

A handful of powerful poems written in Quechua by José María Arguedas who, otherwise, wrote in Spanish.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'The Quechuan Language Family'. W. F. H. Adelaar & P. C. Muysken. In The Languages of the Andes, 179-259. Cambridge University Press (2004).

-

-Ayacucho Quechua Grammar and Dictionary. G. J. Parker. Mouton (1969).

-

-El Quechua y la Historia Social Andina. A. Torero. Lima: Universidad Ricardo Palma (1974).

Quechua

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania