An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Slavic, East Slavic. The other East Slavic languages are Ukrainian and Belarusian. Russian is very close to both of them.

Overview. With more than 160 million native speakers, Russian is the 8th largest language in the world. It belongs to the East Slavic branch of the Indo-European family which has been deeply influenced by Church Slavonic, a South Slavic language, from its earliest stratum (Old East Slavonic) to the present day. Ukrainian and Belarusian became separated from Russian when their homelands fell under Lithuanian hegemony in the mid-thirteenth century.

The most recognizable feature of Russian sounds is widespread palatalization of its consonants (which also occurs in other Slavic tongues). Its nominal morphology has preserved to a great extent the complexity of old Indo-European languages, most notably in its declension system. In contrast, the verb system is far simpler having only two basic tenses and a couple of periphrastic ones. Russian literature is one of the most outstanding in the Western world though its greatest period began only in the 19th century.

Distribution. Russian is the language of nearly all people of the Russian Federation (native or learned) and of substantial minorities in other former republics of the Soviet Union. Among them, Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, the Baltic countries (Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia), and several Central Asian countries (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan). Besides, there are many Russian emigrants in Israel and USA.

Speakers. About 164 million people speak Russian as a first language and about 100 million as a second language. Native speakers are found in the following countries:

Russian Federation

Ukraine

Kazakhstan

Uzbekistan

Kyrgyzstan

Belarus

Israel

USA

Latvia

Moldova

Estonia

Lithuania

141,000,000

11,500,000

4,000,000

1,700,000

1,500,000

1,100,000

750,000

710,000

700,000

560,000

340,000

340,000

Status. Russian is the official language of the Russian Federation; in many autonomous and/or ethnic republics alongside the local language. It is co-official in Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan and is one of the six official languages of the United Nations.

Varieties. Russian has three main dialects distinguished, above all, by their pronunciation:

-

1) Northern dialect (from St. Petersburg eastwards across Siberia).

-

2) Southern dialect (in most of Central and Southern Russia).

-

3) Central dialect (between Northern and Southern dialects).

Modern literary Russian is based on the Central dialect of Moscow.

Oldest Documents. They include religious and secular texts. The first ones were composed in Church Slavonic adapted to East Slavic. Ostromirovo evangeliye ('Ostromir Gospel'), compiled in 1057 by Deacon Grigorij for Prince Ostromir, is the earliest. Secular works, like treaties and codes of law, were written in a more vernacular Russian. Among the latter is Russkaja Pravda ('Russian Law') from mid-11th century.

Periods

Old Russian or Old East Slavic (11th-14th c. CE ). It was characterized by the coexistence between literary Church Slavonic (a South Slavic language), somewhat adapted to the native East Slavonic, and the spoken local language.

Middle Russian (14th–17th c. CE). Ukrainian and Belarusian became separated from Russian.

Modern Russian (18th c. CE-present). Church Slavonic and Russian merged to create the modern literary language.

Phonology

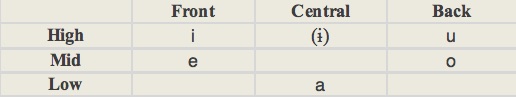

Vowels (5-6). According to some scholars, Russian has five vowels while others think it has six. The controversy is about the phonemic status of the i/ɨ alternation; as ɨ occurs only after non-palatalized consonants, and i only after palatalized ones and word-initially, they could be considered complementary sounds and not separate phonemes. The reduced i and u vowels of the ancestral Slavic language were lost in Russian.

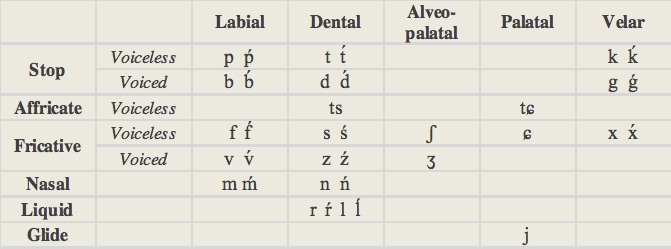

Consonants (36). The phenomenon of consonant palatalization is widespread. Only [ts], [ʃ], [ʒ] lack palatalized counterparts. Conversely, a few consonants, namely [tɕ], [ɕ], [j], are always palatalized lacking a non-palatalized counterpart. [ɕ] is a voiceless palatalized postalveolar fricative.

Palatalization is indicated by an accent over the letter.

Stress: can fall on any syllable and it may serve to differentiate lexical or morphological forms. For instance, muká (‘flour’) versus múka (‘torment’), rukí (genitive singular) versus rúki (nominative plural).

Script and Orthography

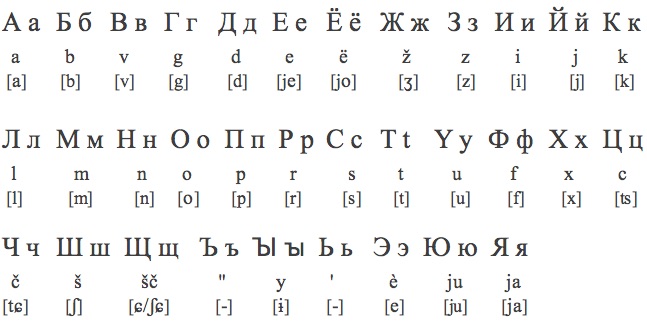

Russian is written with the Cyrillic alphabet composed of 32 letters plus an additional sign to indicate palatalization. It derives from a script created in the 9th-10th centuries based on the Greek uncial (majuscule) script. Ukrainian, Bulgarian and Serbian are written with a similar alphabet. Below each Cyrillic letter its usual transliteration and International Phonetic Alphabet equivalent (between brackets) are shown:

*Ь indicates palatalization of the previous consonant.

*Ъ is silent; it prevents palatalization of the preceding consonant.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Russian nominal morphology has retained part of the complexity of Old Church Slavonic, but it has lost the vocative case, the number of declension types has been reduced and the dual number has disappeared.

-

•gender: masculine, neuter, feminine.

-

•number: singular, plural.

-

•case: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental, locative (or prepositional).

-

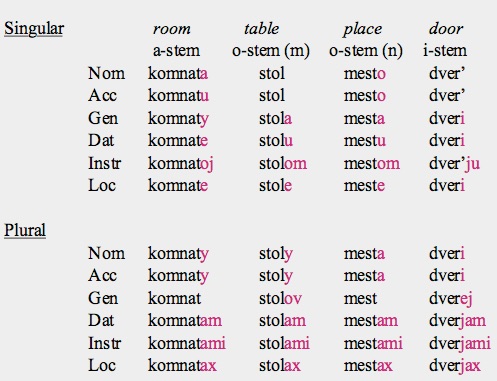

Russian has four major types of noun declension: a-stem, masculine o-stem, neuter o-stem and i-stem.

-

‣Most a-stem nouns are feminine (but those that refer to a male are masculine).

-

‣Almost all i-stems are feminine.

-

‣O-stem nouns are masculine or neuter.

-

Nominative and accusative plural are not differentiated and are the same for a-stem and masc. o-stem, the ending being in both -y. In the plural, dative, instrumental and locative are the same for all stems. In the i-stem, genitive, dative and locative singular are identical to the nominative and accusative plural.

-

In nouns of the o-masculine declension denoting animate beings (as well as their adjectives) the accusative is like the genitive rather than the form shown in the table; in the plural the same thing occurs for all declensions, regardless of gender.

-

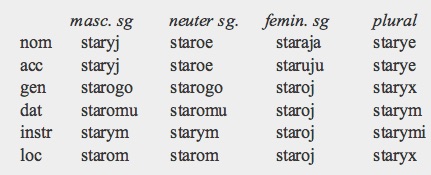

•adjectives: neuter and masculine adjectives differ only in the nominative and accusative. Feminine singular adjectives have one single form for genitive, dative, instrumental and locative. Plural forms don’t distinguish gender. The declension of staryj ('old') is shown in the table.

-

•article: Russian has no definite or indefinite articles.

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

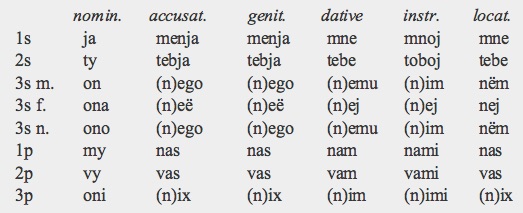

Personal pronouns are declined in the six cases and distinguish gender in the 3rd person singular. Ty is informal and is used when speaking to a friend, relative, child or animal. The 2nd plural form may be used as a polite singular.

-

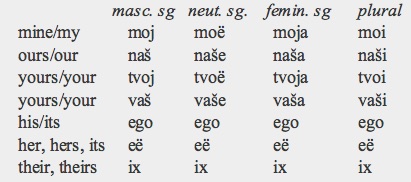

Possessive pronouns/adjectives are declined in all cases and distinguish gender in the singular with the exception of 3rd person forms that are invariable. They have the following nominative forms:

-

Tvoj is the familiar singular form while vaš is not only the plural form but also the polite singular one.

-

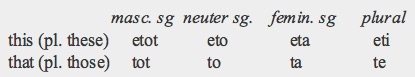

The demonstrative adjectives are:

-

The neuter singular forms are used as demonstrative pronouns.

-

The main interrogative pronouns are kto (‘who?’) and čto (‘what?’). The first one has a possessive adjective: čej (‘whose?’). Other interrogative pronouns, are: kotoryj (‘what?/which?’) and kakoj (‘what kind of?’). All of the above can also function as relative pronouns.

-

Indefinite pronouns are formed by adding the suffixes -to or -nibud' to the interrogative pronouns.

-

There is one reflexive pronoun, sebja (‘himself, herself’).

-

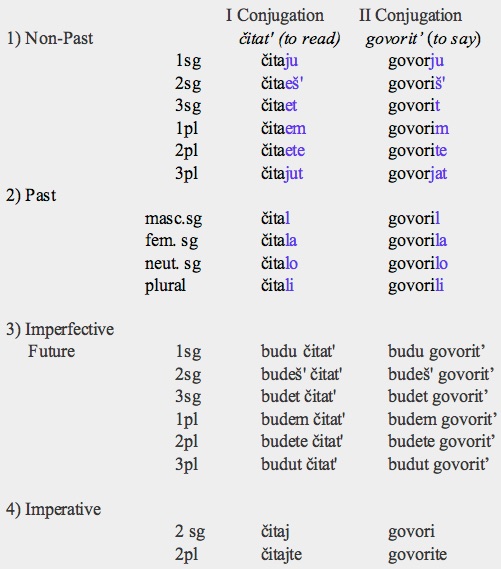

Verbal. In contrast to its nominal morphology, Russian verbal morphology is far more simple than that of Old Church Slavonic and old Indo-European languages in general. The verb has two basic, non-compound tenses (past and non-past), two aspects (perfective and imperfective), two moods (indicative and imperative) and two conjugation types. The only non-finite form widely used is the infinitive.

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p.

-

•mood: indicative, imperative.

-

•tense: past, non-past, imperfective future, conditional.

-

The past and non-past are the only tenses formed without an auxiliary. In the non-past, verbs agree with their subject in person and number; in the past, they agree in gender and number but not in person as this tense derives from a participial form.

-

The imperfective future is formed with the auxiliary budu ('will be'), a future form of the verb to be, plus the infinitive; it may be translated as 'will do' or 'will be doing'.

-

-

The conditional is formed with the past tense + the invariable particle by.

-

•aspect: imperfective, perfective.

-

The first one expresses an incomplete or ongoing action, the second a completed one. Perfective aspect is usually conveyed by adding a prefix to the imperfective form of the verb. The prefix is usually unpredictable; sometimes it doesn't change at all the meaning of the verb (examples 1-2), but often it does (example 3). Conversely, it is possible to derive an imperfective verb from a perfective one by suffixation (example 4). Most Russian verbs come, then, in imperfective-perfective pairs:

-

1) to read: čitat (imperfective), to read: pročitat (perfective)

-

2) to write: pisat (imperfective), to write: napisat (perfective)

-

3) to write: pisat (imperfective), to describe: opisat (perfective)

-

4) to describe: opisat (perfective), to describe: opisyvat (imperfective)

-

•voice: active, passive (infrequent).

-

•non-finite forms: the infinitive is the only common one. There are also participles and gerunds but they are used only in the literary language. There are five participles: present active (‘doing’), present passive (‘being done’), past active imperfective (‘were doing’), perfective (‘having done’), and past passive perfective (‘done’). Participles inflect as adjectives. There are also two gerunds or adverbial participles which are indeclinable.

Syntax

Russian basic word order is a very flexible Subject-Verb-Object. The case system is enough to indicate the function of words in the sentence. Subordinate clauses follow main ones. Adjectives precede their nouns and agree with them in gender, number and case. Russian has prepositions rather than postpositions.

There are no articles and the copula (verb to be) is omitted in the present tense. Finite verbs agree with their subjects in person and number in the non-past tense. In the past tense they agree in gender and number.

Lexicon

The bulk of the lexis is of Slavic origin. The marking influence of Church Slavonic is reflected in the number of words adopted from it, frequently coexisting with the equivalent East Slavic (native Russian) term. Russian has borrowed widely from Western European languages such as German, Dutch, French and English. French has provided, mainly, cultural vocabulary while English has contributed with technical, scientific and socio-political terms.

Basic Vocabulary

one: один (odin)

two: два (dva)

three: три (tri)

four: четыре (četyre)

five: пять (pjat')

six: шесть (šest')

seven: семь (sem')

eight: восемь (vosem')

nine: девять (devjat')

ten: десять (desjat')

hundred: сто (sto)

father: отец (otec)

mother: мать (mať)

brother: брат (brat)

sister: сестра (sestra)

son: сын (syn)

daughter: дочь (dočʼ)

head: голова (golova)

face: лицо (lico)

eye: глаз (glaz), око (oko) (archaic)

hand: рука (ruka)

foot: нога (noga)

heart: сердце (serdce)

tongue: язык (jazyk)

Key Literary Works

-

1185 Slovo o pluku Igoreve (The Song of Igor's Campaign). Anonymous

-

An epic poem in Old Russian, close to oral literature and with lyric touches, preserved in a single manuscript later destroyed, that has become a sort of national icon. It narrates the rash and unfortunate incursion of Igor, prince of Novgorod-Seversk, against the Polovtsy (Kipchak). Defeated and imprisoned he, nevertheless, managed to escape and return to his domain.

-

1560 Letters between Andrej Kurbskij and Ivan the Terrible

-

An epistolary exchange between the aristocrat Kurbskij and Ivan IV the Terrible, in which Kurbskij accuses the monarch of destroying the aristocracy and Ivan, who felt threatened by the nobles and had launched a campaign against them, defends his position as an autocrat with every right over his subjects.

-

1672-73 Zhitiye protopopa Avvakuma (The Life of the Archpriest Avvakum). A. Petrovich

-

This first Russian autobiography is the work of Avvakum Petrovich, an Old Believer intransigent priest who rejected the reform of the Russian Orthodox Church. His ideal was a return to the medieval tradition condemning mundane life and luxuries. He was imprisoned north of the Arctic Circle where he narrated his life in strong and colorful style, employing a predominantly vernacular language. He was finally burnt at the stake.

-

1809-44 Fables. Ivan Krylov

-

Written in colloquial language, they satirize the society of his time disguising basic Russian types as animals. Inspired on Aesop and La Fontaine, these fables acquired in Krylov's hand a sharp social, and sometimes political, edge.

-

1831 Boris Godunov. Aleksandr S. Pushkin

-

Written in prose and verse, this innovative historical tragedy deals with the guilt and inexorable fate of tsar Boris Godunov (1598-1605), presented as the murderer of Dmitry, the little son of Ivan the Terrible. The characters' psychology is shown against the background of the turbulent Russian politics of the Time of the Troubles.

-

1831-33 Yevgeny Onegin (Eugene Onegin). Aleksandr S. Pushkin

-

A novel in verse in which Onegin, a skeptical dandy, a product of insensitive social conventions, rejects the love of Tatyana, and later kills in a duel, unwillingly, his best friend, the young poet Lensky. Several years later, he meets Tatyana again, who has married, and falls in love for her. But now is his turn to be rejected. For Pushkin's neoclassical vision, the right timing and appropriate place of our acts, so difficult to achieve, determines the success or failure of the individual.

-

1840 Geroy nashego vremeni (A Hero of Our Time). Mikhail Lermontov

-

Lermontov, who died in a duel at 26, wove five stories around the same central character, Pechorin, a sort of Romantic hero incarnating the idea of the "superfluous man", ultimately derived from Byron. Young, cynical and bored, impulsive and easily offended, in the climatic story "Princess Mary", he kills his friend, who is a reflection of himself, in a duel.

-

1842 Short Stories. Nikolai Gogol

-

Gogol's short stories rely on the grotesque, the absurd, and the satirical. In Shinel (The Overcoat), a poor clerk buys with great effort a much needed overcoat but, the first time he wears it, it is stolen from him. Humiliated he dies, returning as a ghost who snatches overcoats from people's shoulders. In Nos (The Nose) a nose leaves its face and develops a life of its own. In Zapiski sumasshedshevo (Diary of a Madman) a low civil servant narrates in first person his descent into madness.

-

1850 Svoi lyudi sochtemsya (It's a Family Affair, We'll Settle It Ourselves). Aleksandr

-

Ostrovsky

-

This satirical comedy deals with a false bankruptcy case. The merchant Bolshov trying to save his money from creditors declares himself bankrupt and feigning a sale he passes all his possessions to the commissioner Podchaliusin. In the end Bolshov is imprisoned and the commissioner seizes his properties. Ostrovsky's many other plays have also the emerging merchant class as main subject bringing a sense of realism to the Russian stage.

-

1859 Oblomov. Ivan Goncharov

-

Oblomov is a provincial landlord, an indolent young nobleman, a dreamer, very sensitive, who for some time seems to have found his salvation in Olga, the woman he loves. But he loses her to a half-German friend, pragmatic and full of energy, who incarnates the businesslike efficiency of the new capitalist class emerging in Europe, in contrast with the decadent Russian aristocracy.

-

1862 Otcy i deti (Fathers and Sons). Ivan Turgenev

-

The novel is set in a period of great social change, in the aftermath of Russia's defeat in the Crimean War leading to the emancipation of the serfs. Bazarov, the protagonist, after studying medicine, returns to his provincial home. His new materialistic ideas and independent, critical, views (he calls himself a nihilist) clash with those of the older conservative generation. He falls in love with a woman who eludes him and dies young after having caught an infectious disease from a patient.

-

1866 Prestupleniye i nakazaniye (Crime and Punishment). Fyodor Dostoyevsky

-

Raskolnikov, a poor student from Saint Petersburg, kills an unsavory pawnbroker for her money. He rationalizes his motifs in various ways: she is an oppressor, her cash could be used to help unfortunates like him, good and evil is just a religious idea without substance, extraordinary people (like Napoleon and himself) have the right to extraordinary acts... After the murder, he is haunted by guilt and by an implacable detective until, persuaded by a pure prostitute, he confesses and is sent to Siberia accompanied by her.

-

1868-69 Idiot (The Idiot). Fyodor Dostoyevsky

-

Prince Myshkin is a truly good man, incapable of selfishness, that understands people at the first contact. Subject to fits of epilepsy (like the author), he is a fragile Christ-like figure who because of his innocence is considered an idiot by a morally bankrupt society. The novel ends with the tragic death of the heroine, Nastasya Filippovna, whom he wished to save, and the madness of the prince.

-

1865-69 Voyna i mir (War and Peace). Leo Tolstoy

-

An ambitious work composed of three strands: fictional narrative, historical narrative (the Napoleonic wars), and essays about the meaning and process of history. Great men and intellectuals are contrasted with ordinary people, the real heroes, whose daily prosaic acts shape not only their lives but also war and history.

-

1875-77 Anna Karenina. Leo Tolstoy

-

Anna, a young woman married to an unromantic government minister, falls in love with a young officer. After trying to resist his passion, she abandons her husband and son to follow him but later falls into despair. In this long novel, the stories of the three main characters, Anna Karenina, Aleksei Karenin (the husband) and Aleksei Vronsky (the lover), are interwoven with those of three families of the aristocratic world, the Oblonskys, the Karenins, and the Levins.

-

1876 Gospoda Golovlyovy (The Golovlyov Family). Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin

-

A great satirist, Saltykov switches to a sombre realism in this famous short novel depicting the progressive collapse of a family of landed proprietors, dominated by a matriarch driven solely by greed and whose sons are afflicted by all sorts of vices.

1888-1904 Short Stories. Anton Chekhov

-

Chekhov wrote about fifty short stories and equally masterful dramas in which trivial, everyday situations, hide a deeper unsaid meaning. Feelings are more important than plot, the subtext is more important than the text.

1896-1904 Dramas. Anton Chekhov

-

Chekhov's more mature dramas are: Chayka (Sea-Gull) about art vocation and art related to life, Dyadya Vanya (Uncle Vanya) dealing with wasted lives in a rural estate, Tri sestry (Three Sisters) the portrait of three young nostalgic women with a vague hope in a far distant future, and Vishnyovy sad (The Cherry-Orchard) which blends humor and tragedy to depict the decline of a land owning family who has to sell their property with its symbolic orchard.

-

1910 Derevnya (The Village). Ivan Bunin

-

The clash between two very different brothers, one a cruel drunk and the other a dreamer, living in a peasant world viewed with pessimism, in contrast with the customary idealization of the muzhik. Carefully controlled language and plot, a feeling for nature and accurate psychology are the ingredients of this short masterpiece.

-

1913-23 Autobiographical Trilogy. Maxim Gorki

-

Composed of Detstvo (My Childhood), Vlyudyakh (In the World), and Moi universitety (My Universities). A return to his childhood and adolescence days, a sincere evocation, indignant at the painful moments he lived. 'My Universities', the title of the last volume, is life, the only university he had been to.

-

1926-31 Short Stories. Isaak Babel

-

This Jewish author, executed by Stalin, left two great collections of, mainly autobiographical, stories: Konarmiya (Red Cavalry) and Odesskiye rasskazy (Odessa Tales). The first one, based on his own experiences as a commissar in a Cossack regiment during the Polish war, display the morally complex attitude of an intellectual to absurd cruelty and violence. The second one is located in Moldanka, the ghetto of Odessa where Babel was born, and his "heroes" are a group of Jewish gangsters, led by their legendary "king", as well as other colorful characters of the lower classes.

-

1928-40 Tikhy Don (The Silent Don). Mikhail Sholokov

-

A famous but controversial realist novel in four volumes, depicting objectively the sufferings of the Cossacks from southern Russia (Whites) and their struggle against the Bolsheviks (Reds), during WWI and the civil war in the aftermath of the Revolution. Their speech is recorded faithfully, many folk-songs are included and nature description plays a major role. As other works of Sholokov, a faithful Communist supported by Stalin, are very inferior, many scholars and writers think he plagiarized it from Fyodor Kryukov, a Cossack author.

-

1957 Doktor Zivago (Dr. Zhivago). Boris Pasternak

-

The first revolutionary decades of the 20th century are the background of a poignant personal love story in a harsh world. A multi-layered structure, enhanced by the addition of poetry, intertwines the social and the individual dramas. The primacy of the latter was one of the reasons why this novel was forbidden in Soviet Russia.

-

1973-75 Arkhipelag Gulag (The Gulag Archipelago). Aleksandr Solzenitsyn

-

An authentic description of life in the prisons and labour camps during Stalin's rule based in his own experiences as an inmate and of those of his companions.

-

1940-96 Poems. Iosip A. Brodsky

-

He emigrated to the United States and wrote poems in Russian and English. His poetry is lyric and couched in striking images and powerful rhythm, the exterior landscape of nature reflecting, often, the interior landscape of his feelings. A sense of loss and solitude, the preciousness of the unrepeatable moment, the fragility of human achievements and attachments pervade his work.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Russian'. B. Comrie. In The World's Major Languages, 274-288. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-Russian: A Linguistic Introduction. P. Cubberley. Cambridge University Press (2002).

-

-A Reference Grammar of Russian. A. Timberlake. Cambridge University Press (2004).

-

-The Russian Language in the Twentieth Century. B. Comrie, G, Stone & M. Polinsky. Clarendon Press (1996).

Russian

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania