An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Names: Sinhala, Singhala, Singhalese, Cingalese.

Name Origin: from Sanskrit siṃhala, name of the island of Sri Lanka, and ultimately from siṃha ('lion'), perhaps so called as once abounding in lions.

Classification: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Modern Indo-Aryan. Due to its long geographic isolation, Sinhalese has not obvious relation to any individual Indo-Aryan language of the South Asian mainland. Its only close relative is Dhivehi spoken in the Maldive Islands.

Overview. Sinhalese was introduced in the island of Sri Lanka in the last centuries BCE, where, separated geographically from the South Asian mainland, and from other Indo-Aryan languages by the Dravidian languages of southern India, it developed unique features. Exceptionally among Modern Indo-Aryan languages, Sinhalese has an uninterrupted written record of more than two-thousand years.

Distribution: Sinhalese is the language of three-quarters of the people of Sri Lanka (the rest speaks Tamil). It predominates in every part of the country except the northeast. It is spoken by about 16.3 million.

Status. It is one of the two official languages of Sri Lanka; the other is Tamil.

Varieties. There is little regional variation but there is diglossia involving Spoken Sinhalese and Literary Sinhalese. Both varieties have important morphological, syntactical and lexical differences.

Oldest Documents

Inscriptions in Sinhala Prakrit dating back to the 3rd-2nd centuries BCE.

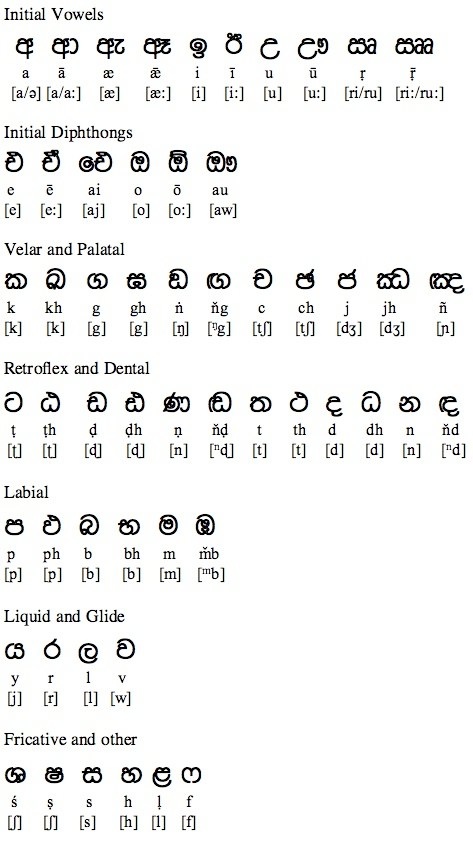

Phonology

Vowels (13). Sinhalese has seven short and six long vowels.

Consonants (25). Sinhalese (along with Dhivehi) is distinguished from other Indo-Aryan languages for its lack of aspirated stops and for the occurrence of prenasalized stops. Sinhalese has 25 consonants in total including 10 stops/affricates, 4 nasals, 4 prenasalized stops, 3 fricatives and 4 liquids and glides. Every series of stops/affricates includes voiceless and voiced consonants, all of them unaspirated. [f] is not a native sound found only in loanwords.

Script and Orthography

The Sinhalese script derives, like all South Asian scripts, ultimately from Brāhmī. Brāhmī evolved into a South Indian version called Grantha which is the precursor of Sinhalese as well as of the different Dravidian scripts. Every consonant has an inherent vowel [a] (not shown here). The Sinhalese alphabet is ordered according to phonetics (below each letter, the standard transliteration is shown followed by the International Phonetic Alphabet notation). Many signs are redundant because they represent sounds existent in Old Indo-Aryan which don’t occur anymore in Sinhalese.

Morphology

-

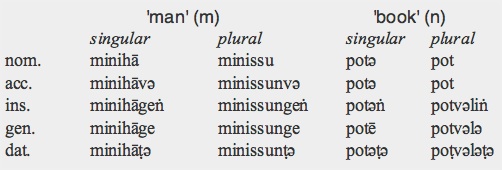

Nominal. Nouns inflect for case, animacy, number and definiteness. Adjectives precede nouns and are indeclinable.

-

•gender: animate masculine, animate feminine, inanimate neuter. The masculine-feminine distinction is only observed in Literary Sinhalese and in some Spoken dialects. Masculine nouns end in -a or -ā, feminine nouns end in -ə or i, neuter nouns end in -ə or -ē.

-

•number: singular and plural. Masculine nouns ending in -a/-ā make their plurals in -o or -u with possible gemination of the final consonant. Most singular feminine nouns end in ə and their plurals in -o or -u. Singular neuter nouns end in ə or ē and their plurals in -val, a nasal or experience apocope. The suffix -lā marks the plural of kinship nouns, pronouns and proper nouns.

-

a)Masculine

-

daruva (child) → daruo (children)

-

horā (thief) → horu (thieves)

-

ætā (elephant) → ættu(elephants)

-

b)Feminine

-

niliə (actress) → nilio (actresses)

-

denə (cow) → dennu (cows)

-

c)Neuter

-

pārə (way) → pārəval (ways)

-

puṭuə (chair) → puṭu (chairs)

-

gasə (tree) → gas (trees)

-

kandə (trunk) → kandaṅ (trunks)

-

d)Kinship nouns, and pronouns

-

ammə (mother) → amməlā (mothers)

-

tāttə (father) → tāttəlā (fathers)

-

oyā (that) → oyālā (those)

-

•case: nominative, accusative, instrumental-ablative, genitive, dative.

-

•definiteness: Sinhalese has an indefinite suffix used only in the singular (-ak/ek), its absence marks definiteness. Masculine nouns usually take -ek while feminine and inanimate ones take -ak. These suffixes come before the case markers.

-

minihā ('the man') minihek ('a man')

-

puṭuvə ('the chair') puṭuvak ('a chair')

-

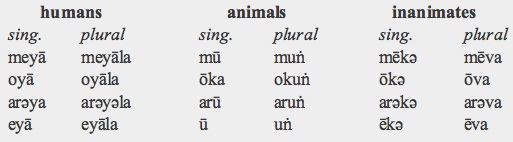

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative.

-

Personal pronouns are used mostly for the first person (singular mama; plural api). There is also a second person familiar form (chē). For polite address, pronouns are avoided, and titles or kinship terms are preferred, like mahattayā ('sir'), nōnā ('madam'), eyā ('he'), ē gollo ('they').

-

Demonstrative adjectives make a four-way distinction: this close to me (mē), that close to you (oya), that close to a visible third person (ara), that close to an invisible third person (ē). They are not inflected for definiteness or number. There are three sets of demonstrative pronouns corresponding to these adjectives:

-

There are two interrogative adverbs, koi ('which?') and mona ('what?'), as well as sets of human, animal and inanimate interrogative pronouns:

-

They are used with the interrogative marker də placed after them.

-

Verbal. In Literary Sinhalese the verb agrees in person, gender and number with the subject. In Spoken Sinhalese there is no agreement at all. There are many compound verbs (noun-verb, verb-verb).

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p in Literary Sinhalese. In Spoken Sinhalese there is no distinction of person and number.

-

•aspect: imperfective (including habitual and continuous actions) and perfective (completed activities).

-

•tense: present, past, and future are the three basic tenses. Combinations of them with participles produce the compound tenses: present continuous, past continuous, past habitual, present perfect, past perfect.

-

The simple present may also have a future or a progressive sense. In Colloquial Sinhalese it is the same as the infinitive, e.g. enavā ('come[s]/ coming/ will come').

-

The simple past is marked by a change in the verbal base, e.g. āvā ('came'). The stem of the verb 'to come' changes from e to āv to æv in different tenses.

-

The future is marked by the suffix -nnam. It is only used in the first person, e.g. ennam ('I/we will come').

-

The continuous and habitual tenses are formed by a repetition of the conjunctive participle plus an auxiliary. The present continuous requires the auxiliary innavā, e.g. katā kara kara innavā ('am/is/are talking'). The past continuous requires the auxiliaries hiṭiyā or unnā, e.g. katā kara kara unnā ('was/were talking').

-

The past habitual uses hiṭiyā as auxiliary and adds the aspect marker -t- to the conjunctive participle, e.g. ævi ævit hiṭiyā ('used to come').

-

The perfect tenses are formed with the conjunctive participle marked by the suffix -lā plus an auxiliary. The present perfect uses the auxiliary tiyenavā (emphatic form tiyenne), e.g. ævillā tiyenavā ('has/have come'). There is also an unspecified perfect without tense marker that has a similar sense, e.g. ævillā ('has/have come'). The past perfect uses the auxiliary ti(b)unā, e.g. ævillā tibunā ('had come').

-

•mood: indicative, presumptive, subjunctive, conditional, imperative.

-

The subjunctive is marked by the suffix -vi; it occurs only in the 3rd person, e.g. ēvi ('he/she/it/they might come').

-

The presumptive requires the auxiliary æti. It has imperfective and perfective tenses. The presumptive imperfective is marked by the affix -n-, e.g. enavā æti ('probably come(s) or am/is/are coming or will come'). The presumptive perfective is marked with the suffix -nna(ṭa), e.g. enna(ṭa) æti ('must have come/been coming').

-

The conditional has also imperfective and perfective tenses; it is marked by the suffix -ot. The conditional imperfective places the aspect marker -t- between the verbal root and the conditional marker, e.g. etot ('if I/he, we, etc come[s]'). The conditional perfective is marked by a change in the verbal base, e.g. āvot ('if I/he/we, etc. came/happened to come').

-

•voice: active and passive.

-

•derivative conjugations: causative. The characteristic ending is -va, with the agent taking the dative case.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, conjunctive participle, present participle, past participle.

-

The infinitive is the citation form and ends in -navā; in Colloquial Sinhalese it serves as the present-future e.g. kanavā.

-

The conjunctive, formed with the suffix -la, expresses an action that takes place before another one.

Syntax

The basic, but not inflexible, word order is Subject-Object-Verb. Sinhalese is a head-final language: noun and verb modifiers precede their heads (but numerals follow the head noun). It has postpositions. Nominal sentences are common. Sinhalese is remarkable for having subjects in case forms other than nominative. Relative clauses end in a verb and as the clause boundary is clearly marked they do not require a relative pronoun.

Lexicon

Sinhalese has loanwords from Sanskrit, Dravidian, English, Dutch and Portuguese. In spite of the prevalence of Buddhism in the island, it has few borrowings from Pali.

Basic Vocabulary

one: eka

two: deka

three: tuna

four: hatara

five: paha

six: haya

seven: hata

eight: aṭa

nine: namaya

ten: dahaya

hundred: sīya

father: piyā

mother: mava

brother: bāyā

sister: akka

son: puta

daughter: duva

head: sira, oluva

eye: æsa

foot: kakula, aḍiya

heart: hadavata

tongue: diva

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Sinhala'. J. W. Gair. In The Indo-Aryan Languages, 847-904. G. Cardona & D. Jain (eds). Routledge (2007).

-

-A Grammar of the Sinhalese Language. W. Geiger. Royal Asiatic Society (1938).

-

-Colloquial Sinhalese. G. H. Fairbanks, J. W. Gair & M. W. S. De Silva. Cornell University (1968).

-

-Literary Sinhala. J. W. Gair & W. S. Karunatilaka. Cornell University (1974).

-

-An introduction to Spoken Sinhala. W. S. Karunatillake. Gunasena (1992).

Sinhalese

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania