An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Germanic, North Germanic. The other languages in this branch are Norwegian, Danish, Icelandic and Faroese.

Overview. At first, the North Germanic languages were divided into two groups according to an east-west division. In one group the dialects spoken in Norway, Iceland and Faroese Islands and in the other the dialects of Sweden and Denmark. In 1526, when Sweden won independence from Denmark and the first Swedish translation of the New Testament was made, Modern Swedish was born. Swedish is reasonably mutually intelligible with mainland Scandinavian languages as it shares many phonological and morphological characteristics with Norwegian and Danish.

Distribution and Speakers. Swedish is spoken by about 9 million people in Sweden (almost 100% of the population) and by around 300,000 in Finland (in the coastal areas, including Ostrobothnia, the Åland archipelago, Finland Proper and Uusimaa).

Status: It is the national language of Sweden and one of the two official languages of Finland.

Varieties. Besides Standard Swedish, there are several regional dialects spoken in North Sweden, South Sweden, Svealand, Gotland, Götaland, and Finland.

Oldest Documents

The earliest written records in Scandinavia are runic inscriptions in a Proto-Germanic language, dating back to 200 CE and originating in the Danish peninsula of Jutland.

800-1100. Runic inscriptions in Eastern Old Norse found in Sweden (the dialect of Old Norse spoken in Denmark and Sweden).

early 13th c. Documents in Old Swedish written in the Latin alphabet, including the Västgötalagen provincial law code.

1526. A translation of the New Testament was the first text printed in Modern Swedish.

Periods

1225-1375. Early Old Swedish

1375-1525. Late Old Swedish

1525-present. Modern Swedish

Phonology

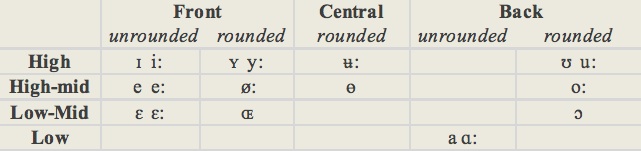

Vowels (18). Swedish has a relatively complex vowel system composed of 18 vowels. They are grouped in nine pairs. Members of a given pair differ in length (short and long vowels), but there are also associated differences in quality. Swedish has no phonemic diphthongs.

The nine short-long pairs are:

-

Front: [ɪ]-[i:], [e]-[e:], [ɛ]-[ɛ:], [ʏ]-[y:], [ɶ]-[ø:]

-

-

Central-Back: [ɵ]-[ʉ:], [ʊ]-[u:], [ɔ]-[o:], [a]-[ɑ:]

Consonants (17). Initial stops p, t, k are aspirated in stressed position, but unaspirated when preceded by s within the same morpheme. t, d, s, n, l, before [r] are pronounced as retroflex. ɕ is a voiceless palatalized postalveolar fricative.

An additional voiceless fricative occurs in some Swedish dialects but its phonemic status and exact place and manner of articulation are controversial. Some authors consider it a doubly articulated “dorsopalatal/velar fricative” ([ʃ] + [x]), usually represented with the special symbol [ɧ].

Accent. In Swedish (except in Swedish spoken in Finland) there is a tonal distinction between accent 1 (acute) and accent 2 (grave). The difference between them is one of pitch. Accent 2 only occurs in disyllabic and polysyllabic words. Some words are only differentiated by their accent e.g., anden with accent 1 is 'duck' but with accent 2 is 'spirit'. Stressed syllables must contain a long consonant or a long vowel.

Script and Orthography

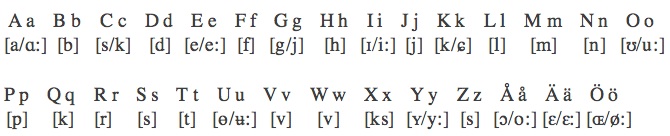

Eastern Old Norse was first written in runes carved on stone. Later, the Latin alphabet was brought by Christian missionaries. Modern Swedish uses an alphabet of 29 letters including three additional ones placed at its end to notate vowel sounds not found in Latin. Below each letter, its equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown between brackets. There are some sounds represented by more than one symbol.

-

•q, w, z are found only in proper names and in loanwords.

-

•[ŋ] is written with the digraph ng.

Morphology

-

Nominal. The nominal morphology is richer than the verbal one. Nouns are marked for number and definiteness; gender is revealed by agreement with modifiers.

-

•case: only the genitive is marked in nouns by adding an -s at its end. Pronouns have subject and object forms (see below).

-

•gender: common, neuter. Masculine and feminine genders have merged into one, called common gender or utrum. Gender is marked by accompanying articles, adjectives and pronouns. Some dialects still distinguish between masculine and feminine (besides neuter). In the plural, gender distinction is neutralized.

-

•number: singular, plural. The plural is marked with -ar, -or, -er, -n or zero originating five declension types. There may be vowel changes in the stem (umlaut). For example:

-

I)häst (horse) → hästar (horses)

-

II)flicka (girl) → flickor (girls)

-

III)son (son) → söner (sons)

-

IV)äpple (apple) → äpplen (apples)

-

V)barn (child) → barn (children)

-

•definiteness: is marked morphologically on nouns by means of suffixes. In the singular -(e)n is the marker for common gender and -(e)t for neuter. In the plural, -na is the marker for most nouns except for some neuter nouns of the fifth declension that add -en; definiteness markers are placed after the plural marker.

-

I)hästen (the horse) → hästarna (the horses)

-

II)flickan (the girl) → flickorna (the girls)

-

III)sonen (the son) → sönerna (the sons)

-

IV)äpplet (the apple) → äpplena (the apples)

-

V)barnet (the child) → barnen (the children)

-

brown: plural marker; blue: definiteness marker.

-

Definiteness can be also expressed by the use of articles.

-

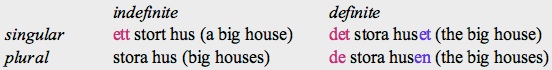

•articles: Swedish has indefinite and definite articles (indefinite singular, definite singular and definite plural). The indefinite articles are en for common gender and ett for neuter (they have no plural). Definite articles are used mainly with attributive adjectives. They are: singular common gender den, singular neuter det, and plural de. For example:

-

Common gender

-

red: article; blue: definiteness marker.

-

Neuter gender

-

red: article; blue: definiteness marker.

-

When an article is used, definite marking is double because the definite suffix attached to the noun is not dropped.

-

•adjectives: are marked for gender, definiteness and plurality agreeing with their nouns. They have usually only three forms: one for indefinite common gender singular, one for indefinite neuter singular, and another for the rest six combinations of gender, number and definiteness (see above). The comparative is made by suffixing -(a)re to the adjective, and the superlative by suffixing -(a)st.

-

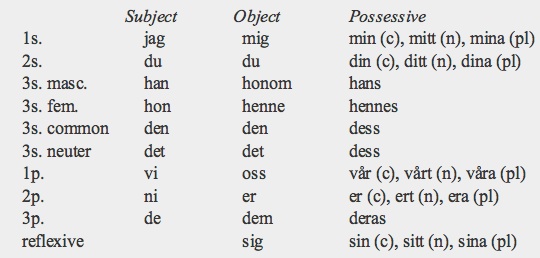

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite, relative.

-

Personal pronouns have subject and object forms; they distinguish gender in the 3rd person singular. Swedish possessive pronouns are the result of two systems, one of them includes pronouns inflected like adjectives and the other invariable forms. The personal and possessive pronouns are:

-

Swedish has two series of demonstrative pronouns. One is the same as the definite article, but stressed: den (common gender sg.), det (neuter sg.), de (plural). The other is a bit more formal or emphatic: denna (common gender sg.), detta (neuter sg.) dessa (plural). As they do not differentiate between near and far they can be further qualified by adding här (‘here’) or där (‘there’).

-

The interrogative pronouns are vem (‘who?’) and vad (‘what?’).

-

Swedish has two relative pronouns: som and vilken. Som is invariable and cannot follow a preposition, while vilken is inflected (neuter vilket, plural vilka , genitive vars).

-

Verbal

-

•person and number: are not marked in the verb.

-

•tense: present, past, perfect, pluperfect, future, future perfect, conditional present, conditional past.

-

Only the present and past tenses are formed without auxiliaries. The past, along with the past participle, is the basis of the distinction between 'weak' and 'strong' verbs. Strong verbs when conjugated in the past lack any marking suffix but a vowel change (umlaut) occurs in the stem. Their present is made, like that of weak verbs, by suffixing -(e)r to the stem. There are seven classes of strong verbs, as shown above.

-

Weak verbs form the past by adding -de to the stem and their past participle ends in -t. There are three classes of weak verbs:

-

•mood: indicative, imperative, subjunctive. The imperative is formed by eliminating the final vowel of the infinitive except in weak verb classes 1 and 3 in which is the same as the infinitive.

-

•voice: active, passive. There are two passive forms, one ends in -s, and the other is formed with the auxiliary verb bli (‘to become’) plus the past participle. The first form refers to general or objective facts while the second form refers to a specific event.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, past (or perfect) participle, present participle.

-

Most infinitives end in a and are preceded by att; many verbs have also shortened infinitive forms, e.g. ‘to give’ has two infinitives: giva and ge . Short forms also occur in the present and imperative, e.g. giver and ger are alternative present forms of ‘to give’. The present participle ends always in -nde. Both participles may be used as adjectives; the past participle is inflected, then, like an adjective; the present participle is invariable. The neuter form of the past participle, called the supine, is used to form compound tenses.

Syntax

Independent and subordinate clauses have the same Subject-Verb-Object word order as English. In questions the order of subject and verb is inverted. Adverbs that modify the whole sentence follow immediately the verb. Relative clauses are introduced by the particle som. Conditional clauses are introduced by om (‘if)’. In impersonal sentences det is the formal (dummy) subject.

In a noun phrase the order is: determiner-modifier-noun. Modifiers agree in number and definiteness with the noun they modify, but gender agreement is only observed in the indefinite singular.

Lexicon

Swedish vocabulary contains many words from Low and High German and from French and English.

Basic Vocabulary

one: en/ett

two: två

three: tre

four: fyra

five: fem

six: sex

seven: sju

eight: åtta

nine: nio

ten: tio

hundred: hundra

father: far/fader

mother: mor/moder

brother: bror/broder

sister: syster

son: son

daughter: dotter

head: huvud

face: ansikte

eye: öga

hand: hand

foot: fot

heart: hjärta

tongue: tunga

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-'Swedish'. E. Anderson. In The Germanic Languages, 271-312. E. König & J. van der Auwera (eds). Routledge (1994).

-Swedish: A Comprehensive Grammar. P. Holmes & I. Hinchliffe. Routledge (1994).

-Swedish. Essentials of Grammar. A. Viberg, K. Ballardini & S. Stjärnlof. Passport Books (1993).

Swedish

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania