An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Altaic?, Turkic, Norththwestern (Kipchak) branch, Northern group. Tatar is a member of the Turkic family. The external classification of Turkic is disputed. Many consider it one of the three divisions of the Altaic phylum but for others its relationship with Tungusic and Mongolic is not proven. Tatar belongs to the northern group of the Kipchak branch along with Bashkir.

Overview. Tatar is the product of complex linguistic and historical processes. Turkic-speaking peoples arrived in the middle Volga River region from the 5th century CE and in the 9th century the Volga Bulgar state was founded. It was destroyed by the Mongols of the Golden Horde who created a Khanate in 1237. Tatar has a strong Volga Bulgar element tinged with Golden Horde and local influences. It is different from Crimean Tatar with which should not be confused. It is a typical Turkic language, very similar to Bashkir, with agglutinative morphology based on suffixes, verb-final syntax and vowel harmony.

Distribution. Tatar is spread over a vast area within the Russian Federation with most speakers living in the autonomous Republic of Tatarstan. The Republic is located in the centre of the European portion of the country, in the middle Volga river basin, and its capital is Kazan. Tatars are also present in western Siberia and in Central Asia, especially in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

Speakers. There are about 5.4 million speakers of Tatar in the following countries:

Russia

Uzbekistan

Kazakhstan

Tajikistan

Kyrgyzstan

Turkmenistan

Azerbaijan

4,300,000

470,000

330,000

80,000

70,000

40,000

32,000

Status. Tatar is, with Russian, the official language of the Republic of Tatarstan. It is spoken by about 85 % of the Tatars of the Russian Federation.

Varieties. Kazan Tatar is the literary language spoken in Tatarstan, Mishar Tatar (also known as Western Tatar) is spoken in the Volga region outside the Republic, and Eastern dialects are spoken in western Siberia.

Oldest Document. Kitāb-i Yūsuf (The Book of Joseph). An adaptation of the Quranic story of Joseph, composed between 1200-1230.

Phonology

Vowels (9): Tatar has front and back vowels, rounded and unrounded. The mid-vowels are shorter than the fully articulated high and low vowels.

The symbols are those current in then Tatar Latin alphabet; those of the International Phonetic Alphabet are indicated between brackets. The diacritical marks placed above the mid vowels indicate that they are extra short.

Vowel harmony. It governs the distribution of vowels within a word opposing front versus back vowels. In the first syllable of a word all vowels can occur. If it is a front vowel all the subsequent vowels must be also of the front type. If it is a back vowel all the other vowels must be also of the back type. Thus, all the vowels of a word belong to the same class (back or front) and the vowels of suffixes vary according to the class of vowels in the primary stem. The harmony based on roundness, typical of most Turkic languages, is not prominent in Tatar.

Consonants (26): When the velar voiceless stop is accompanied by back vowels it is realized as [q], when it is accompanied by front vowels it is realized as [k]. When the velar voiced stop is accompanied by back vowels it is realized as [G], when it is accompanied by front vowels it is realized as [g].

-

c, v, ʒ and h are found only in loanwords.

Stress: falls usually on the last syllable of the word.

Script and Orthography

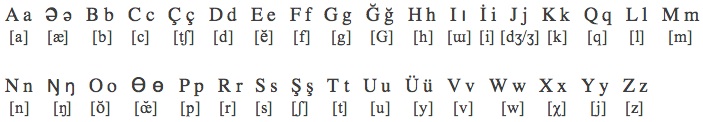

Until 1927 Tatar was written with the Arabic script when it was replaced by the Latin alphabet. In 1939, a modified Cyrillic script was adopted. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union a new version of the Latin alphabet was created although it is not still of universal use. In 2002 the Russian Parliament mandated the use of Cyrillic scripts for all official languages in the Russian Federation creating a conflict with the Republic of Tatarstan. The Tatar Latin-based alphabet has 34 letters of which 9 are vowels and 25 consonants (below each letter, its equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown):

Suffixes variants. Due to sound harmony all vowels and some consonants of suffixes change according to the preceding sounds. This is indicated with capital letters as follows:

-

A indicates a low vowel that is realized as ə [æ] after a front vowel, or as a [a] after a back vowel.

-

E indicates a high vowel that is realized as e [ĕ] after a front vowel, or as ı [ɯ] after a back vowel.

-

D may be realized as d, t or n.

-

K may be realized as k or q, and G may be realized as g or ğ.

Morphology. Tatar is an agglutinative language adding different suffixes to a primary stem to mark a number of grammatical functions. Each morpheme expresses only one of them and is clearly identifiable.

-

Nominal. Suffixes are added to nominal stems to indicate number, possession and case (in that order).

-

•gender: there is no grammatical gender.

-

•number: singular and plural. The singular is unmarked and the plural is marked with the suffix lar/lər. Unmarked forms can have also a generic/collective meaning. Nouns following a numeral are usually left in the singular.

-

•possession: there are six possessive markers, one for each person and number, which are attached to the noun.

-

1s-(E)m

-

2s -(I)ŋ

-

3s-(s)E

-

1p -(E)bEz

-

2p-(E)GEz

-

3p-(s)E

-

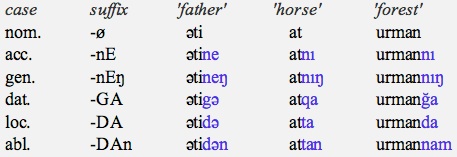

•case: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, locative, ablative.

-

The nominative is unmarked. The other cases are marked with the suffixes shown in the table.

-

The nominative is employed for subjects, the accusative for the direct object, the genitive forms for possessive attributes, the locative is for complements of place and time, the dative is used to mark a goal, aim or direction, and the ablative a source.

-

•comparatives and superlatives: superlatives are formed by adding the particle iŋ before the adjective, comparatives are expressed by adding the suffix rak/rək to the adjective e.g. ozonraq ('longer'). Intensive adjectives are formed by partial or total reduplication.

-

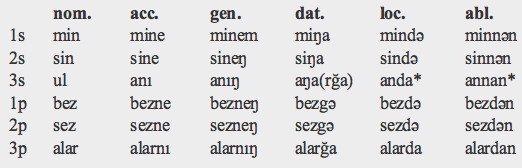

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, reflexive, interrogative, indefinite.

-

Personal pronouns are declined in all cases:

-

* 3s has also aŋarda for locative an aŋardan for ablative.

-

There are five demonstrative pronouns expressing three deictic categories:

-

this : bu (plural bolar)

-

this here: şuşı (plural şuşılar)

-

that: şul, tege, ul (plurals şular, tegelər, alar)

-

The reflexive pronoun üz takes possessive suffixes (for each person and number) and declines like a noun in the six cases: üzem ('myself'), üzeŋ ('yourself'), üze ('himself'), üzebez ('ourselves'), üzegez ('yourselves'), üzləre ('themselves').

-

The interrogative pronouns are kem ('who?'), nərsə, ni, qay/qaysı ('what?'), niçe ('how many?').

-

Indefinite pronouns are based on the interrogative ones: hərkem ('everybody'), hərnərsə ('everything'), hiçkem ('nobody'), hiçnərsə ('nothing').

-

Verbal

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p.

-

•tense-aspect: present, simple past, perfect (gan past), pluperfect, imperfect, habitual past, aorist, prospective.

-

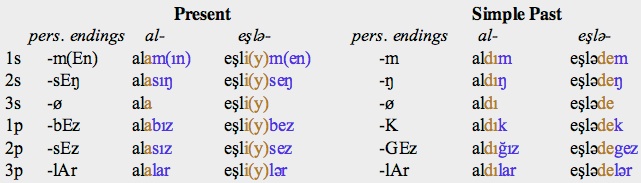

Tense and aspect (progressive, habitual, perfective) are intimately connected. The present and simple past are marked by specific suffixes added after the stem and before the personal endings. The present uses -A- after a consonant and -I(y)- after a vowel (which it replaces). The past is marked by -DE-. Most of the personal endings of the past tense are different from those of the present. The conjugations of al- ('take') and eşlə- ('work') are:

-

The other tenses are made with participles or converbs which may be combined with the copula (verb 'to be'):

-

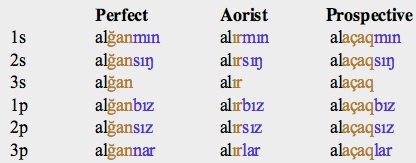

The perfect is formed with the -GAn participle followed by present personal endings (though the 3rd plural ends in -nAr instead of -lAr).

-

The pluperfect is formed with this same participle + the past tense of i ('be'). The imperfect is formed with a converb + the past tense of i. The habitual past is formed like the imperfect but with the addition of torğan.

-

The aorist, which expresses predicted events, is formed with the aorist participle -(Vowel)r plus the same personal markers as the present.

-

The prospective has a future sense, and is formed with a different participle, -(y)AçAK, but with the same personal markers. For example, we have these forms for the verb al- ('take').

-

•mood: indicative, optative-imperative, conditional.

-

The conditional is formed with the suffix -sA plus past personal markers, while the optative-imperative has no marker but is identified by its distinctive personal endings.

-

•voice: active, reflexive, passive, cooperative-reciprocal.

-

•non-finite forms: verbal nouns, participles, converbs.

-

The most common verbal noun is formed with the suffix -(Vowel)w e.g. aluw ('taking'); less frequently it is formed by suffixing -mAK e.g. almaq.

-

The converb formed by adding -A /-I(y) to the stem indicates events simultaneous with that of the main verb e.g. ala. The -(E)p converb expresses an action beginning before that of the main verb e.g. alıp. The -GAç converb expresses an action which precedes that of the main verb.

-

Participles are present, past, necessitative, future, aorist and adjectival:

-

‣The present participle is formed with the -A converb plus the -GAn past of the auxiliary verb tor (torğan) e.g. ala torğan ('taking')

-

‣The past participle is formed with -GAn as a suffix e.g. alğan ('taken').

-

‣The necessitative participle is formed with the suffix -AsE/ysE e.g. alası ('bound to take').

-

‣The prospective or future participle has the suffix -(y)AçAK.

-

‣The aorist participle is formed with the suffix -(Vowel)r.

-

‣The participle that functions as an adjective has the suffix -(E)wçE.

-

Syntax

Tatar, like all Turkic languages, has a basic Subject-Object-Verb word order which, nevertheless, can be changed to highlight a certain topic. It is head final, modifiers preceding their head. In a nominal phrase the order is demonstrative pronoun, numeral, adjective, noun. In comparative constructions, adjectives occur after nominals marked with ablative case.

In general, nominal phrases do not present morphology agreement. Subject and verb must agree in person but, most often than not, there is no agreement in number (plural subjects often have a predicate in singular). Pronominal subjects may be dropped. Constructions combining converbs with auxiliary verbs are frequent. Negation is expressed by using special negative forms of the verb. Yes/no questions can be posed by rising intonation or with the particle -mE. Information-seeking questions require interrogative pronouns or adverbs. Coordinated clauses may be linked by conjunctions or juxtaposition.

Lexicon

The core vocabulary is Turkic. Loanwords are of Middle Mongolian, Arabic, Persian, Russian and Uralic origin.

Basic Vocabulary

one: ber

two: ike

three: ɵç

four: dürt

five: biş

six: altı

seven: jide

eight: sigez

nine: tuğız

ten: un

hundred: yɵz

father: ata, əti

mother: ana, əni

elder brother: aha

younger brother: ini

sister: seŋel

son: oğul

daughter: qiz

head: baş

eye: küz

foot: ayak

heart: yɵrək

tongue: til, tel

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Tatar and Bashkir'. Á. Berta. In The Turkic Languages, 283-300. L. Johanson & É. Á. Csató (eds). Routledge (1998).

-

-Tatar Manual: descriptive grammar and texts with a Tatar-English glossary. N. Poppe. Indiana University Publications, Uralic and Altaic Series 25 (1963).

-

-Historical anthology of Kazan Tatar verse: voices of eternity. D. J. Matthews & R. Bukharaev. Curzon Press (2000).

Tatar

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania