An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Dravidian, South Central. Other major South Central languages are Gondi, Kui and Kuvi.

Overview. Telugu is the largest Dravidian language and one of the most important regional languages of India. Less conservative than Tamil, its sound system and lexicon have been deeply influenced by the Indo-Aryan languages of north and central India. It is agglutinative, adding suffixes to nominal and verbal stems to indicate grammatical categories such as case, number, person and tense. It has its own script and has developed an outstanding literature.

Distribution. Telugu is spoken mainly in the state of Andhra Pradesh, located in southeast India, as well as in the neighboring states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Orissa.

Speakers. Telugu is the mother tongue of 86 million people who live mostly in these six Indian states (speakers in millions): Andhra Pradesh (74.1), Tamil Nadu (4.1), Karnataka (4.3), Maharashtra (1.6), Orissa (0.8), West Bengal (0.2).

Status. It is the official language of the state of Andhra Pradesh and one of the 23 scheduled languages of India.

Varieties. Telugu has literary and colloquial varieties. Literary Telugu includes an older, heavy Sanskritized, form and a more modern one that is becoming the standard. Colloquial Telugu has four regional dialects spoken in north, south, east and central Andhra Pradesh.

Periods

600-1100. Old Telugu.

1100-1600. Middle Telugu.

1600-present. Modern Telugu.

Oldest Documents. The first Telugu inscription dates back to c. 575 CE and the first literary works appeared in the 11th century.

Phonology

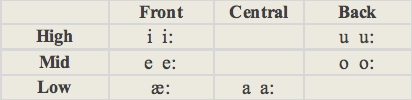

Vowels (11). Telugu has five short and six long vowels. In addition to the inherited system of five basic vowels (short and long), it has developed a long [æ].

Vowel harmony: though not typical of Dravidian languages, vowel harmony is present in Telugu. Inflectional suffixes harmonize with the vowels of the preceding syllable.

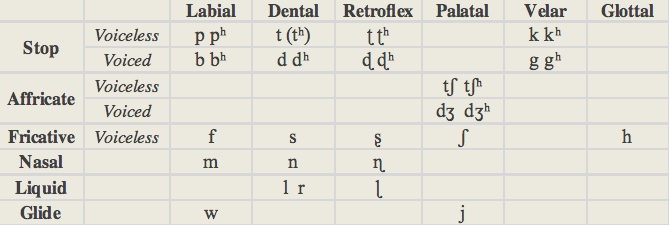

Consonants (33). Besides a Dravidian consonantal inventory, Telugu has aspirated stops and affricates as well as supplementary sibilants borrowed from Sanskrit. However, [th] is rarely found and is replaced by [dh]. In addition, it has borrowed f from Urdu which itself borrowed it from Arabic; it is used mainly in Perso-Arabic and English loanwords. w varies between [w] and [v].

Sandhi: internal and external sandhi are commonplace. They result in vowel and consonant deletion, assimilation of consonants and fusion.

Script and Orthography.

Telugu is written in an abugida script, derived from the ancient Brāhmī script, in which every consonant carries an inherent a. It is very similar to that used for Kannada. The signs for initial vowels (shown here) are different from those for internal vowels (not shown). Alphabetic order is based on phonological principles: it starts with simple vowels and diphthongs followed by 25 stops and nasals arranged in five groups according to their place of articulation, it continues with the semivowels (liquids and glides) and ends with the fricatives.

Below each Telugu sign appears the standard transliteration in the Latin alphabet, and between square brackets its equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet:

[æ:] doesn't have a specific sign and is usually represented as ā.

ṛ is a syllabic vowel found only in Sanskrit loanwords.

The velar and palatal nasals [ŋ] and [ɲ] and ] are not native Telugu sounds but are found in Sanskrit loanwords.

*[f] is found mostly in Urdu and English loanwords and doesn't have a specific sign, it is represented with ph that also serves for [pʰ].

Morphology

Telugu is agglutinative adding suffixes to a root to indicate case, person, number and tense. Other suffixes are derivatives employed to create new words or to change the syntactic category of a word.

-

Nominal. Nouns and pronouns are marked for case and number. There are very few adjectives; attributive adjectives are invariable and precede the noun. There is no definite article; the number one can be used as an indefinite article.

-

•gender: is not marked on the noun, but it is indicated on the 3rd person of the verb and on demonstrative pronouns. There are two genders which are not equivalent in the singular and in the plural. In the singular, the genders are human maleness and other than human maleness: the latter includes women and all non-humans. In the plural the gender distinction is between human (male and female) versus non-human (male and female).

-

•number: singular, plural. The latter is marked by the addition of the suffix -lu/-ḷu:

-

kukka (‘dog’)→kukkalu (‘dogs’)

-

pilli (‘cat’) → pillulu (‘cats’)

-

kannu (‘eye’) → kaḷḷu (‘eyes’)

-

•case: nominative, genitive, accusative, dative, instrumental-comitative, ablative, locative.

-

Nouns and pronouns have both direct and oblique stems. Direct stems are used in the nominative case. The oblique stem marks the genitive and is also the base for the remaining cases which are marked by adding suffixes to it: accusative (-ni/-nu), dative (-ki/-ku), instrumental-comitative (-tō), ablative (-nunci), and locative (-lō). If the noun is plural the case suffix comes after the plural marker:

-

bomma-l-a-ku (‘to the dolls’)

-

bomma: noun stem (‘doll’), l: plural marker, a: oblique stem marker, ku: dative suffix

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative.

-

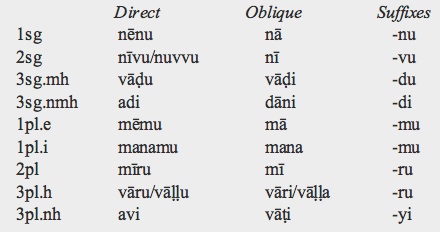

Personal pronouns distinguish person, number, and gender (in the 3rd person only). Besides, there are inclusive and exclusive 1st person plural pronouns. Independent personal pronouns have a direct stem for the nominative case and an oblique stem which is the base for the other cases. The pronominal suffixes attached to the conjugated verbs are shortened versions of the independent pronouns.

-

e = exclusive (excludes the addressee)

-

i = inclusive (includes the addressee)

-

mh = human male

-

nmh = other than human male

-

h = human

-

nh = non-human

-

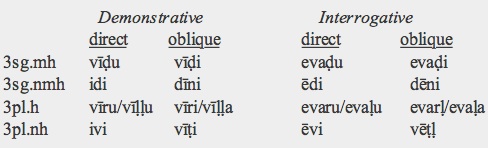

Demonstrative pronouns, which are inflected for gender and number, recognize proximate and remote locations. They have direct and oblique stems.

-

The near demonstratives (‘this’) are formed by replacing the a of 3rd person pronouns by i. The remote demonstrative pronouns (‘that’) are identical to the 3rd person pronouns.

-

Interrogative pronouns like demonstratives, distinguish gender and number, and have direct and oblique stems. They are formed by adding an initial e to a 3rd person pronoun or by replacing its initial a by e.

-

Verbal. An inflected verb is composed by stem + tense/mood suffix + personal endings. The stem can be simple (formed by one verb root), derived (from a verbal or nominal root plus a derivative suffix), or compounded (main verb + auxiliary verb).

-

•tense-mood: past, nonpast, negative tense, durative, imperative, negative imperative, hortative.

-

The colloquial language has only past and non-past tenses.

-

The marker of the past tense is -æ:- (represented as ā), and the marker of the non-past is -t(ā)-. The latter expresses an habitual or future meaning. The negative conjugation has no tense marker and, thus, it serves for both past and non-past; the negative marker is -a-. The personal endings are the same for every tense. The conjugation of tinu ('to eat') is: shown in the table.

-

black: verb stem, red: tense marker, blue: personal endings

-

-

The durative is formed with the suffix -ṭunnā plus personal endings, for example: 3s.mh tiṇṭunnādu (‘he is/was eating’).

-

The imperative is formed by the stem plus personal endings for 2nd person singular (u) or plural (aṇḍi): 2sg tinu, 2pl tinanḍi.

-

The negative imperative is formed with the suffix -ak plus personal endings: 2sg tinaku, 2pl: tinakaṇḍi.

-

The hortative is formed with the suffix -dā plus personal endings: 1pl tindām (‘let us eat!’).

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, verbal noun, past participle, non-past participle, negative participle.

-

They are formed by adding a suffix to the stem and they lack person and number marking. The past and non-past participles serve to make relative clauses.

-

infinitive: cadawa (‘to read’)

-

verbal noun: cadawaḍam (‘reading’)

-

past participle: cadiwina (‘one who read/one which was read’)

-

non-past participle: cadiwē (‘one who reads/one which is/will be read’)

-

negative participle: cadawani (‘one who does/did not read; one which is/was not read’)

Syntax

Telugu has Subject-Object-Verb word order in the sentence, indirect object preceding direct object. Syntactic functions are conveyed by case suffixes and postpositions that follow the oblique stem. It is head-final i.e., genitive, and adjectives precede the head noun, and adverbs precede the verb. It is a pro-drop language i.e., the subject can be omitted since the verb itself marks person and number.

Telugu lacks coordinating conjunctions; coordinated phrases lengthen their final vowels. To form relative clauses a relative participle is used instead of the finite verb.

Lexicon

The earliest borrowings came from Sanskrit and Prakrit, some of them were adapted to Telugu phonology. Later, loanwords from Perso-Arabic, Urdu, Portuguese and English were incorporated.

Basic Vocabulary

one: oṇḍu, okaṭi

two: reṇḍu

three: mūḍu

four: nālugu

five: aidu

six: āru

seven: ēḍu

eight: enimidi

nine: tommidi

ten: padi

hundred: nūru/vanda

father: abba

mother: amma, tāyāru, tāyi

elder brother: anna

younger brother: tammuḍu

elder sister: akka

younger sister: cellelu, celli, cellāyi

son/daughter: biḍḍa, boṭṭe

head: tala

face: mōmu

eye: kanu, kannu

hand: kay

leg/foot: kālu

heart: eda

tongue: nālika, nāluka

Key Literary Works. Forthcoming.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Telugu'. Bh. Krishnamurti. In The Dravidian Languages, 202–240. S. B. Steever (ed). Routledge (1998).

-

-A Grammar of Modern Telugu. Bh. Krishnamurti & J. P. L. Gwynn. Delhi, Oxford University Press (1985).

-

-An Introduction to Modern Telugu. P. Subrahmanyam. Annamalai University (1974).

Telugu

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania