An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Bodish.

Overview. Tibetan is the language of the Tibetan people who inhabit the Tibetan Plateau and neighboring Himalayan regions. The Tibetans emerge into history in the 7th century CE coinciding with their adoption of an alphabetic writing system, modeled on an Indian one, and the introduction to Tibet of Mahayana Buddhism. The Classical Tibetan language was the vehicle for the spread of Tibetan Buddhism in the north of the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia and Mongolia. In the meantime it evolved into many dialects which due to physical and political barriers became quite divergent and in some cases not mutually intelligible. Classical Tibetan didn't have tones but several modern dialects have developed a tone-system. Tibetan stems are monosyllabic but they combine easily with prefixes and suffixes, or with other stems to form compound words.

Distribution. Tibetan is spoken in the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China and the Chinese provinces of Yunnan, Sichuan, Gansu, and Qinghai, in Bhutan, northern India (Ladakh, parts of Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim), Pakistan (Baltistan), Nepal (Mugu, Dolpo, Mustang, Solu Khumbu).

Varieties. Tibetan comprises a standardized written language (Classical Tibetan) and many regional dialects, often mutually unintelligible, which may be grouped in the following way:

-

•Central or U-Tsang:

-

Lhasa: in the capital of Tibet and as a lingua franca in all of Tibet

-

Shigatse: southern Tibet

-

Sherpa: Nepal and northeastern India (West Bengal, Sikkim, Arunachal Pradesh)

-

Kagate: eastern Nepal (Janakpur)

-

•Western Archaic

-

Ladakhi: Ladakh region in northwestern India

-

Purik: Ladakh

-

Balti: Baltistan region in north Pakistan

-

•Western Innovative

-

Lahul: Himachal Pradesh in northern India

-

Spiti: Himachal Pradesh in northern India

-

•Southern

-

Sikkimese: Sikkim region in northeastern India

-

Dzonghkha: in Bhutan

-

•Khams: eastern Tibet; west Sichuan, northwest Yunnan and southwest Qinghai Chinese provinces.

-

•Amdo: northeastern Tibet, and Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu

Speakers. It is difficult to estimate accurately their number. We think there are at least 5 million Tibetan speakers (including all dialects), in the following countries: China (4,200,000), India (400,000), Pakistan (300,000), Bhutan (200,000), Nepal (100,000).

The approximate number of speakers for each Tibetan dialect is:

Khams

Lhasa1

Amdo

Balti

Ladakhi

Dzongkha

Sherpa

Sikkimese

Purik

Spiti

Lahul

Kagate

1,800,000

1,200,000

1,000,000

320,000

180,000

175,000

85,000

75,000

38,000

10,000

2,500

1,300

1. Includes also other dialects of central Tibet.

Status. Almost all writings are in Classical Tibetan. The spoken dialects are seldom written and there is a wide gap between spoken and written forms of the language. For political reasons some of them, like Dzongkha and Ladakhi, tend to be considered separate languages though they are close to Lhasa Tibetan. Lhasa Tibetan serves as a lingua franca in the Tibetan Autonomous Region and among the members of the exile communities. Dzongkha plays a similar role in Bhutan, and the same can be said of Leh Ladakhi in Ladakh and Amdo in Qinghai and Gansu.

Oldest Documents

760 CE. An inscription on a stone pillar in Lhasa.

8th- 9th c. CE. Several documents and inscriptions including a number of texts discovered in the caves at Dunhuang.

Phonology

Syllable structure: all syllables have a Consonant-Vowel nucleus (CV). Initial consonant clusters are frequent but are limited in final position. Thus, the syllable structure is (C)(C)(C)CV(C). In Lhasa Tibetan all consonants can occur as onsets but only p, m, k, ŋ as codas.

Vowels: Proto-Tibeto-Burman had i, u, e, a, o which are preserved without change in Classical Tibetan. Lhasa Tibetan has these same five basic vowels plus three or four additional ones:

In Lhasa Tibetan, vowels may be short or long but vowel length is rarely phonemic. Vowels may be nasalized, and nasalization is contrastive. It exhibits vowel harmony: when a word contains a high vowel the other vowels in the word are raised.

Consonants: Classical Tibetan has 30 consonantal sounds. Stops and affricates come in three series: voiceless unaspirated, voiceless aspirated, and voiced. The contrast between the voiceless aspirated and unaspirated series is of minor importance since both series are in complementary distribution in the verb, and voiceless unaspirated consonants are rare initially in lexical stems.

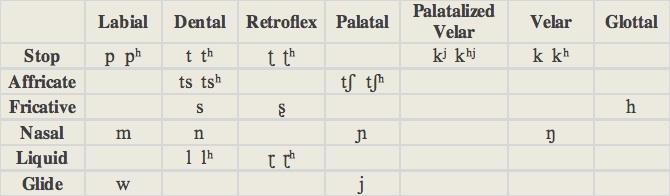

Lhasa Tibetan has 27 consonants. The voiced series of Classical Tibetan stops, affricates and fricatives have entirely disappeared. It has acquired retroflex and palatalized velar sounds:

Tones: There is no evidence of tones in Classical Tibetan but modern central, southern and Khams dialects have a well-developed tone lexical system that might have arisen to compensate for the loss of many initial consonant clusters. For example, Lhasa Tibetan has a low tone and a high tone affecting the first (or only) syllable. In contrast, the western dialects Ladakhi and Balti as well as Amdo lack tones.

Script and Orthography

If there is a consonant cluster, one consonant is taken as the root initial. Consonants which precede it are written above or before it; consonants which follow are written beneath it. Syllable and phrase boundaries are marked but there is no marking of word boundaries.

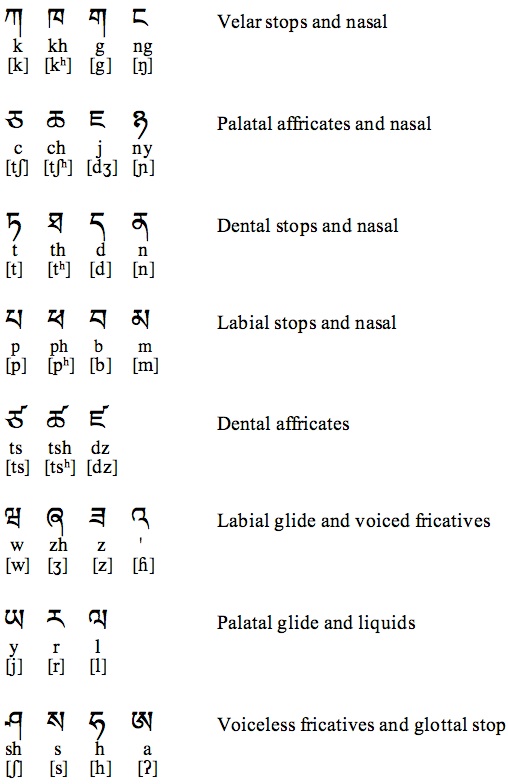

The arrangement of the alphabet reflects that of its Indian model and the sound system of Classical Tibetan (its 30 consonants have a one-to-one correspondence with the 30 basic sounds).

It is shown below with the Wylie transliteration system underneath, and its phonetic equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet between square brackets (the inherent a is not represented).

Morphology (Lhasa Tibetan).

Some Tibetan nouns are monosyllabic but the majority are disyllabic, combining a monosyllabic lexical stem with a noun suffix (like pa, po and mo) or, alternatively, two noun stems to form a compound.

-

Nominal. Nouns are marked for case by postpositional particles and, sometimes, for gender and number.

-

•case: postpositions following noun phrases mark case relations. They are attached to the last word of a noun phrase, whether or not it is the head noun. The cases of Lhasa Tibetan are: nominative/absolutive (unmarked), genitive, ergative/instrumental, locative, ablative. Tibetan is ergative, i.e. the subject of a transitive verb is marked in the ergative case (identical to the instrumental) contrasting with the zero marking of intransitive subjects (absolutive).

-

•gender: Tibetan has no grammatical gender. Certain particles may mark natural gender, like po (masculine) and mo (feminine). For example: rgyal-po ('king'), rgyal-mo ('queen'). The nominal suffix pa is indeterminate regarding gender. For example: lag.pa ('hand').

-

•number: plural is not obligatory marked, but several particles can be used to specify plurality. The commonest are tsho, rnams, and cag.

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative.

-

Personal pronouns have honorific forms for the second and third person. Besides, third person pronouns distinguish gender. The plural is made by adding the suffix tsho.

-

The demonstratives are di ‘this’ and de ‘that’. Their plural is formed with the suffix tsho. Distal de also functions as a definite article, contrasting with the indefinite article cig (an unstressed form of gcig ‘one’).

-

The interrogative pronouns are su ('who?') and ga.re ('what?').

-

•compounds: are commonplace in Tibetan.

-

‣Some combine two synonyms like in nam.kha ('heaven') formed by gnam ('heaven') + mkha ('heaven') or in sgra.skad ('sound') formed by sgra ('sound') + ska ('sound').

-

‣Others combine two antonyms like in che.chung ('size') made of che ('big') + chung ('small').

-

‣Other compounds are determinative which may be head-final or head-initial. For example ngam.gru ('aircraft') is a head-final compound formed by ngam ('sky') + gru ('boat') while glang.chen ('elephant') is a head-initial one made of glang ('ox') + chen ('great').

-

‣Other compounds are copulative (joined by an imaginary 'and') like pha.ma ('parents') formed by pha ('father') and ma ('mother') or rkang.lag ('limbs') combining rkang ('foot') + lag ('hand').

-

Verbal.

-

In Classical Tibetan, verbs have from one to four temporal stems distinguished by a vowel and/or consonantal change. For example, the verb 'to cut' has the following stems: gcod (present), bcad (past), gcad (future), chod (imperative). Modern spoken dialects show a reduction in the number of verb stems; in Lhasa dialect there is no future stem and many verbs have been reduced to a single stem: the equivalent of either the present or past of the classical language. In compensation for this reduction, modern dialects use a great variety of particles and auxiliaries to express tense, aspect, mood, and evidentiality.

-

Past, present and future tenses are established by a combination of verb stem and auxiliary. Perfective, progressive, and prospective aspects are conveyed by suffixes. Other suffixes indicate evidentiality, like direct evidence, indirect evidence, etc. A reduplicated verb stem in conjunction with perfective conjugation may express regular or repeated action.

Syntax

The neutral word order is Subject-Object-Verb but any preverbal element can be fronted. The order of elements in the noun phrase is: (1) genitive modifier, (2) head noun (3) adjective, (4) demonstrative, (5) quantifier, (6) case marker. Sometimes numerals occupy the position of adjectives, preceding the demonstratives.

The main clause is the last in the sentence. Non-final verb clauses are usually marked by special subordinating particles. Several clauses may be chained sharing a common verb, though two-clause chains are the commonest.

Lexicon

Indian culture was a great civilizing force that lent Mahayana Buddhism and Tantrism to Tibet while at the same time provided its language with many Sanskrit loanwords and a writing system. As thousands of Sanskrit texts were translated into Tibetan it was necessary to develop a specialized religious and philosophical vocabulary. Very often, instead of just borrowing the term from Sanskrit, Tibetan translators created Tibetan neologisms calqued on Sanskrit.

Basic Vocabulary

one: gcig

two: gnyis

three: gsum

four: bzhi

five: lnga

six: drug

seven: bdun

eight: brgyad

nine: dgu

ten: bcu

hundred: brgya

father: pa.pha

mother: a.ma

elder brother: co.cog

younger brother: 'og.ma

elder sister: a.cag

younger sister: 'og.ma

son: sras

daughter: bu.mo

head: mgo

eye: mig

foot: rkang.pa

heart: snying

tongue: lce

Literature

Until recently, Tibetan literature has been almost exclusively Buddhistic, consisting in translations of Sanskrit works and original philosophical and religious compositions virtually unknown outside Tibet. Only since the late 20th century, other genres, like novels, short stories and modern poetry have appeared. Excepting these later developments, the single secular work is the epic Rgyal-po Ge-sar dgra-'dul gyi rtogs-pa brjod-pa (The Great Deeds of King Gesar, Destroyer of Enemies) in which the hero Gesar Khan defeats various enemies, including several demons, and descends into hell before returning to heaven.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-Tibetan. P. Denwood. John Benjamins (1999).

-

-The Classical Tibetan Language. S. Beyer. University of New York Press (1992).

-

-Modern Literary Tibetan. M. C. Goldstein. University of Illinois Press (1973).

-

-'Classical Tibetan'. S. DeLancey. In The Sino-Tibetan Languages, 255-269. G. Thurgood & R. J. LaPolla (eds). Routledge (2003).

-

-'Lhasa Tibetan'. S. DeLancey. In The Sino-Tibetan Languages, 270-288. G. Thurgood & R. J. LaPolla (eds). Routledge (2003).

Tibetan

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania