An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Name: isiZulu

Classification: Niger-Congo, Volta-Congo, South Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Eastern Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Bantu. Based on shared characteristics and on territorial contiguity, Guthrie grouped the Bantu languages into 15 geographical (and partly genetical) zones. In Guthrie's classification Zulu belongs to Group S40 (Nguni). Zulu is close to Xhosa, Swati and Ndebele.

Overview. Zulu is the mother tongue of the Zulu people, South's Africa largest ethnic group, who created an empire in the 19th century. It is a southern Bantu language with typical Bantu agglutinative morphology which includes a noun-class system commanding agreement at the nominal, pronominal and verbal levels. It has tones and a rich consonantal system that contains click sounds, ejectives and implosives.

Distribution. It is spoken in eastern South Africa, especially in the Zululand area of KwaZulu-Natal province as well as in Transvaal, Lesotho and Swaziland. Also in parts of Malawi, Tanzania and Mozambique.

Speakers. Native speakers of Zulu are around 12 million, and a further 20 million use it as a second language. It is spoken by 11,5 million people in South Africa, 400,000 in Lesotho, 90,000 in Malawi, and 3,500 in Mozambique.

Status. Zulu is one of South Africa's eleven official languages. It is used in the media, and in the national and provincial parliaments.

Varieties. The main Zulu dialects are: Kwabe, Lala and Niguni (in Malawi and Tanzania). Ndebele or Mtabele is a closely related language spoken by about 2 million in Zimbabwe. Xhosa could be considered a dialect of Zulu but their speakers see them as separate languages.

Oldest Documents

-

1883.Translation of the Bible into Zulu.

-

1903.Appearance of the Zulu newspaper Ilanga lase Natal (The Natal Sun), one of the first in a native African language.

-

1933.Publishing of the first Zulu novel Insila ka Chaka, written by John Dube.

Phonology

Syllable structure: Zulu syllables usually end in a vowel, and consonant clusters are not allowed except for the combination nasal-non nasal consonant. Thus the typical syllable has a (N)CV structure.

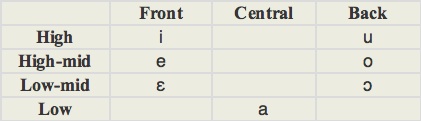

Vowels (7). Like about one-third of Bantu languages, Zulu has a 7-vowel system. Each vowel can be long or short but vowel length is distinctive only occasionally:

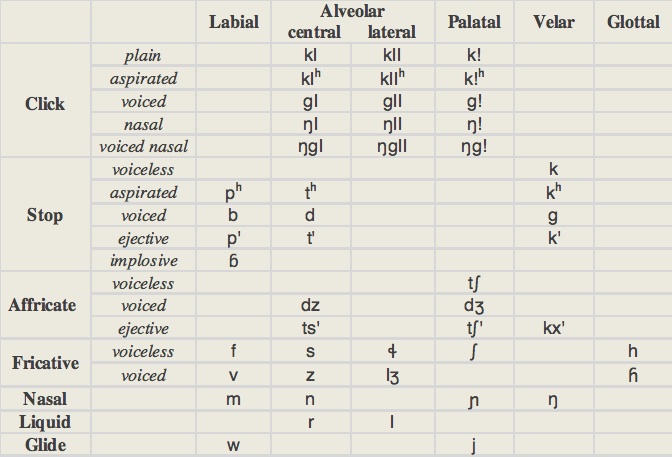

Consonants. Zulu has close to 50 consonants including clicks, ejectives and implosives. Clicks originated in Khoisan languages and then spread into some neighboring Bantu ones. In Zulu they have three places of articulation: central alveolar, lateral alveolar and palatal combined with five accompaniments (plain, aspirated, voiced, nasal, and voiced nasal).

Tones: like most Bantu languages, Zulu is a tonal one. It has just two tones, high and low.

Stress: usually falls on the penultimate syllable.

Script and Orthography.

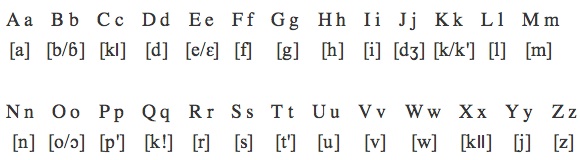

Zulu is written with a 26 letter Latin alphabet, identical to that of English. The equivalence of each letter in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown between brackets:

-

•long vowels and tones are not marked.

-

•high-mid and low-mid vowels are not distinguished.

-

•the ejectives p', t', and k' are represented by p, t and k, respectively. The last symbol serves also for plain k.

-

•the implosive [ɓ] is not differentiated from [b].

-

•many sounds are rendered by combinations of two and three letters (digraphs and trigraphs).

Clicks are represented like this:

Other sounds are represented:

Morphology

Zulu has a predominantly agglutinating morphology. Like other Bantu languages, it has a noun-class system and marks morphologically the agreement between different constituents of clauses and sentences. It has very few adjectives.

-

Nominal

-

•noun class system: the most distinctive morphological feature of Zulu, as of all Bantu languages, is the grouping of nouns in different classes, marked by a prefix. All members of a given class share the same prefix. Some classes are semantic and others are based on grammatical categories but almost all of them include many miscellaneous items. There is no gender distinction. Zulu has 15 noun classes. Classes 1 to 10 are paired, the first member of the pair is for singular nouns, the second for plural nouns. Classes 12-13 have merged with others, and classes 1-2 have subdivided.

-

Classes 1-2 for persons.

-

Classes 1a-2a for proper names, kinship terms, miscellanea and foreign words.

-

Classes 3-4 for trees, rivers and other nouns.

-

Classes 5-6 for parts of the body and other nouns.

-

Classes 7-8 are heterogeneous.

-

Classes 9-10 include animals and miscellanea.

-

Class 11 for long things. Uses plural of class 10.

-

Class 14 for abstract qualities (without plural).

-

Class 15 for infinitives (without plural).

-

•agreement system: it involves nominal, pronominal and verbal agreement.

-

Adjectives, demonstratives, possessives and relatives agree with the noun by the use of affixes. Verbs agree with subject and object by the use of subject and object markers. The shape of agreement affixes is not always identical with the noun-class prefix. While the agreement morpheme is identical to the noun class prefix in the case of adjectives, other concord markers may have a different shape. For example, the noun 'children' belongs to class 2 (human, plural) and its class prefix is aba-; the adjective 'small' has the same prefix but the possessive has a slightly different one:

-

aba-ntwana ba-khe aba-ncane

-

children his small

-

His small children

-

•numbers: singular and plural. Plural is indicated by a prefix according to the system of noun-classes:

-

classes 1-2: umfana (boy), abafana (boys)

-

classes 1-2: umngane (friend), abangane (friends)

-

classes 3-4: umuthi (tree), imithi (trees)

-

classes 3-4: umfula (river), imifula (rivers)

-

classes 5-6: ikhanda (head), amakhanda (heads)

-

classes 7-8: isihlalo (seat), izihlalo (seats)

-

classes 9-10: imfene (baboon), izimfene (baboons)

-

classes 11-10: uphondo (horn), izimpondo (horns)

-

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

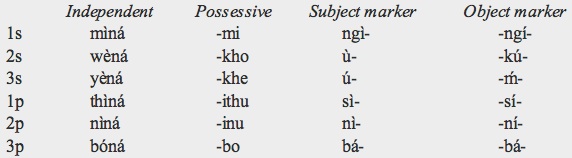

Personal pronouns may be independent, possessive, verb-subject markers and verb-object markers (though tones are not normally written we show them here for clarification; high tone is represented by an acute accent and low tone by a grave accent):

-

-

Independent pronouns are optative and used mainly for emphasis. When they are employed they don't replace the subject markers in the verb complex. Possessive pronouns are prefixed by class markers.

-

Subject and object markers shown here are those of noun-classes 1 (singular) and 2 (plural) which are for humans. Other classes have different markers for the 3rd person (they don't have 1st and 2nd person markers as they include only non-human nouns). Subject and object markers not belonging to classes 1-2 are identical within each class.

-

Demonstrative pronouns differentiate three positions; in classes 1-2, they are: proximal (sg. lo, pl. laba), intermediate (sg. lowo, pl. labo) and distal (sg. lowaya, pl. labaya). They can be used before or after the noun.

-

Verbal. The verb shows always concord with the subject (except in the imperative) and sometimes with the object as well. The minimal Zulu conjugated verb includes: subject marker-tense marker-root-mood/aspect marker. The verb complex may also include negative, relative and object markers as well as derivational affixes. The markers and verb root follow a precise order filling up to ten possible slots which are not all of them occupied at the same time:

-

1. pre-initial negative marker

-

2. relative marker

-

3. subject marker (SM)

-

4. post-initial negative marker

-

5. tense marker

-

6. object marker (OM)

-

7. root

-

8. derivational affixes

-

9. final (indicating mood/aspect/polarity)

-

10. post-final

-

•The negative marker can precede or follow the subject marker (positions 1 and 4 are mutually exclusive). The pre-initial negative marker a is the most widely used; the post-initial negative marker (nga) is used to negate the subjunctive and infinitive.

-

•The relative marker a is used to build a relative clause and agrees with the class of the subject noun/pronoun.

-

•The subject marker indicates the class, person and number of the subject and is obligatory except in the imperative.

-

•The tense markers are zero or ya for the present indicative, long a for the remote past, za for the immediate future, ya for the remote future, nga for the potential and conditional. Negative conjugations have a different set of tense markers. The tense marker is obligatory except in some forms of the present, the imperative and the subjunctive. A recent past or perfect can be formed by using an aspect marker in final position (number 9).

-

•The object marker indicates the class, person and number of the object; it is optional.

-

•The root can be extended with a number of derivational suffixes like passive w, applicative el, causative is, and reciprocal an. More than one derivational suffix is possible.

-

•The final suffix may encode mood (subjunctive), aspect (perfect), and polarity (negative actions). The default one is a but in the perfect and present subjunctive is replaced by e. In most negative conjugations the final element is i but in the negative perfect it is anga.

-

•The post-final slot may be occupied by a small number of additional affixes or clitics, including the -yo ending found in relative constructions, the -ni suffix of the plural imperative, and Wh-clitics such as -phi (where?).

-

As an example, we show the conjugation of the verb cula ('to sing') in the 3rd person singular corresponding to noun-class 1:

-

present short: ucula (SM u-cul-final a)

-

present long: uyacula (SM u-TM ya-cul-final a)

-

neg. present: akaculi (NG a-SM ka-cul-final i [neg. pres.])

-

recent past short: ucule (SM u-cul-final e [perfect])

-

recent past long: uculile (SM u-cul-final ile [perfect])

-

neg. recent past: akaculanga (NG a-SM ka-cul-final anga [neg. past.])

-

remote past: wa:cula (SM w-TM a:-cul-final a)

-

potential: angacula (SM a-TM nga-cul-final a)

-

neg. potential: angecule (SM a-TM nge-cul-final e)

-

immediate future: uzocula (SM u-TM zo-cul-final a)

-

immediate future neg.: akazucula (NG a-SM ka-TM zu-cul-final a)

-

remote future: uyocula(SM u-TM yo-cul-final a)

-

remote future neg.: akayucula (NG a-SM ka-TM yu-cul-final a)

-

present subjunctive: acule (SM a-cul-final e)

-

present subjunctive neg.: angaculi (SM a-NG nga-cul-final i)

-

past subjunctive: wacula (SM w-TM a-cul-final a)

-

past subjunctive neg.: wangacula (SM w-TM a-NG nga-cul-final a)

-

conditional: angacula (SM a-TM nga-cul-final a)

-

conditional neg.: wangacula (SM w-NG a-TM nga-cul-final a)

-

imperative singular: cula (cul-final a)

-

imperative plural: culani (cul-final a-postfinal ni)

-

infinitive: ukucula (CM15 uku-cul-final a)

-

infinitive neg.: kungaculi (CM15 uku-NG nga-cul-final i)

-

SM: subject marker, TM: negative marker, NG: negative marker, CM: class marker.

-

-The short forms are used when the verb is followed by an object, otherwise the long forms are employed. In the present tense, the long form is the one which exhibits -ya-, while the short form lacks it. The recent past tense also has a long and short alternation which has a distribution identical to that of the present tense pattern. In this tense, the short form ends in -e, while the long form ends in -ile.

-

-The subjunctive and negative forms use (k)a as a 3rd singular SM (instead of u).

-

-The remote past and the affirmative past subjunctive differ in both tone and vowel length of the prefix, but they are orthographically identical.

-

-The infinitive is formed with the prefix of noun-class 15 (uku).

Syntax

Basic word order is Subject-Verb-Object-Adjunct. Zulu is head-initial i.e. noun modifiers, like adjectives, possessive phrases and relative clauses, follow their noun. However, demonstratives may precede or follow the noun. Subject verb agreement is shown by the subject marker incorporated as a prefix in the verb complex. The subject marker not only indicates person and number but also agrees with the noun-class of the subject. There are also independent pronouns but their use is optional. For example:

-

Ngi-cul-ile izolo

-

SM 1s-sing-PERF yesterday

-

I sang yesterday.

Ngi is SM for the 1st person singular of class 1(human, singular), cul is the verb root, ile is the perfective marker which denotes a recent past. [There is another perfective marker (e) used when the verb has an object]. Izolo like other verb complements follows the verb.

An OM (object marker) may be included in the verb complex and when that occurs it agrees with the object in person, number and class. Let's see an example with the potential that is used to express possibility or ability:

-

Ngi-nge-yi-cul-e le ngoma

-

SM 1s-NG-OM 9-sing-NG POT this 9 song 9

-

I can't sing this song.

The subject is incorporated in the verb as SM, then follows the negative marker nge, the OM corresponding to class 9 yi (that of song), root cul, and the final element corresponding to the negative potential e. After the verb complex comes le, a demonstrative corresponding to class 9, and a noun of class 9 ngoma.

Lexicon

Zulu has borrowed many words from other languages, especially Afrikaans and English.

Basic Vocabulary

one: nye

two: bili

three: thatu

four: ne

five: hlanu

six: isithupa

seven: isikombisa

eight: isishiyagalombili

nine: isishiyagalolunye

ten: ishumi

hundred: ikhulu

father: ubaba

mother: umama

brother (colloquial): buti

my brother: umfowethu

his brother: umfowabo

sister (colloquial): sisi

my sister: udadewethu

his sister: udadewabo

son: indodana

daughter: indodakazi

head: ikhanda

eye: iso

foot: unyawo

heart: inhliziyo

tongue: ulimi

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

-

Further Reading

-

-Textbook of Zulu Grammar. C. M. Doke. Longman (1986).

-

-Teach Yourself Zulu. A Complete Course for Beginners. A. Wilkes & N. Nkosi. McGraw-Hill (1996).

-

-'Phonetic analysis of Afrikaans, English, Xhosa and Zulu using South African speech databases'. T, Niesler, P. Louw & J. Roux. In Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, Volume 23, 4 (2005).

Zulu

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania