An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Afro-Asiatic, Semitic, West Semitic, Central Semitic. Arabic shares traits of both Southwest and Northwest Semitic subgroups.

Overview. Arabic is the fifth largest language of the world and, by far, the largest Semitic language. It is the liturgical language of Islam and as the Quran, the holy book of Islam, is composed in it, Arabic is of importance to all Muslims even to those for whom it is not their mother tongue. Originating in the north and centre of the Arabian peninsula, Arabic spread, along with Islam, to the entire Middle East, Central Asia and the north of Africa.

Distribution. It is spoken in a large area, covering the Arabian Peninsula (Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait) and other parts of the Middle East (Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq) as well as in North Africa (Mauritania, Western Sahara, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Chad, Sudan), and the Horn of Africa (Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, Comoros). Significant minorities exist in Iran and Turkey, in western Europe and North America.

Speakers. Arabic is spoken by about 310 million people as a first language, most of whom live in the Middle East and North Africa. Native Arabic speakers are found in the following countries:

Egypt

Algeria

Morocco

Saudi Arabia

Iraq

Yemen

Sudan

Syria

Tunisia

Jordan

Libya

Lebanon

Palestine

Mauritania

Oman

Kuwait

U.A.E.

Israel

Iran

France

Chad

USA

Qatar

Turkey

Bahrain

Western Sahara

Eritrea

78,000,000

30,000,000

27,000,000

26,000,000

25,000,000

24,000,000

23,000,000

21,000,000

10,500,000

6,300,000

6,300,000

4,100,000

3,800,000

3,300,000

2,700,000

2,500,000

2,200,000

1,550,000

1,500,000

1,100,000

1,000,000

770,000

750,000

700,000

650,000

500,000

250,000

Status. Arabic is one of the six official languages of the UN and is the official language of 26 countries. All across the Arab world there is diglossia, i.e. two forms of the language coexist, literary and colloquial, each serving a different function (see below).

Varieties

Modern Standard Arabic: is a modernized version of Classical Arabic used with little variation in all Arabic-speaking countries for written and formal oral communication.

Colloquial Arabic: includes numerous spoken dialects, some of which are mutually unintelligible. There are five major dialect groups in: 1) Arabian Peninsula, 2) Iraq, 3) Syria and Palestine, 4) Egypt, Sudan and Chad, 5) the Maghreb (North Africa to the west of Egypt). The Arabic dialects have been strongly influenced by, and in turn had influenced, the literary language.

Periods

-

•Pre-Classical Arabic is represented by a few inscriptions and, more importantly, by a considerable body of oral poetry.

-

•Classical Arabic was the universal language of the Arabic empire between the 8th and 10th centuries CE. A vehicle of a highly refined religious and scientific literature as well as of belles-lettres, it became normative in the Islamic world. So much so, that Modern Standard Arabic, based on Classical Arabic, is the literary language used in most current printed publications, is spoken in the media across North Africa and the Middle East and understood by most educated people. In spite of its name, Modern Standard Arabic belongs, with Classical Arabic, to an old stage of the language that could be called 'Old Arabic'.

-

•New Arabic is distinguished from Classical Arabic by its loss of the case endings in nouns and adjectives, the loss of the mood category in the verb, and the loss of the dual number. When and how New Arabic emerged is disputed, but it most likely happened after the Islamic conquest. Today, it is represented by the various dialects of colloquial Arabic.

Oldest Documents

Thousands of short graffiti written in Ancient North Arabic, found scattered over the Syrian and especially North Arabian desert, dated between the 6th century BCE and the 5th century CE, are the first evidence of a language similar to, but not quite yet, Arabic. The first attestation of Arabic proper is a funerary inscription found in Namara (southeastern Syria), written in the Nabatean script, dating back to 328 CE. The tomb belonged to Imru' al-Qays, second king of the Lakhmid dynasty, and the text tells about his military exploits. The first inscription in the Arabic alphabet, which derived from the Nabatean one, was written in 512 CE and found also in Syria (Zabad).

Phonology (Modern Standard Arabic)

Vowels (6): Modern Standard Arabic has, like Proto-Semitic, three short and three long vowels, plus two diphthongs. Vowel length is phonemic.

-

Front: i, i:

-

Diphthongs: aw, ay

-

Central: a, a:

-

Back: u, u:

Pronunciation of Arabic vowels is influenced by neighboring emphatic consonants (see below) and is quite variable in the colloquial languages. Many dialects have developed other vowels such as e, ə, o, etc.

Consonants (30). Arabic has, like other Semitic languages, a remarkable number of very back consonants (uvular, pharyngeal and glottal). Arabic consonants can be voiceless, voiced or emphatic. The emphatic consonants are produced with constriction of the pharynx (pharyngealized). Every consonant may be geminated (doubled). Modern Standard Arabic lacks a p-sound but some dialects have one.

ðˤ is pronounced zˤ in Egypt, Syria and other countries.

dʒ is usually replaced by g in Egypt and by ʒ in other countries.

Stress: is variable and dependent upon the rules of the colloquial languages.

Script and Orthography

The Arabic alphabet is, very likely, an offspring of the Nabatean alphabet, itself derived from an Aramaic one. Its earliest evidence dates from 512 CE. It is written from right to left and contains 28 letters, all of them consonants.

Though the Arabic script doesn't have specific letters to represent the vowels, the signs for alif, waw and yā' might be used to represent the long vowels ā, ū, and ī, respectively. The shape of the letters changes according to their position in the word (initial, medial, final); if a letter is written alone it is similar or identical to the word-final form.

The Arabic alphabet is shown here, including in the first column the name of the letters, in the second the Arabic symbols (isolated forms), in the third the symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet, in the fourth the standard transliteration in the Latin alphabet, in the fifth an alternative transliteration.

The hamza is not considered a full letter but a diacritic which is added to alif to mark a glottal stop. In transliteration it is often omitted.

Morphology (Modern Standard Arabic). A word is composed of two parts: the root formed by three consonants (less frequently by two or four), and the vowels. The root gives the basic lexical meaning of the word and the vowels give grammatical information.

-

Nominal. Nouns, adjectives and pronouns are marked for gender, number, definiteness and case.

-

•definiteness: indefiniteness is generally marked by the suffix -n (lost in Colloquial Arabic). Definiteness may be indicated by the article 'al, which is prefixed to the noun, by a pronominal suffix or by a following genitive. Thus, indefinite kitābun (a book) and definite 'alkitābu (the book).

-

•case: nominative, accusative and genitive.

-

Each case is marked by a different final vowel: u for the nominative, a for the accusative and i for the genitive (for example 'the book': 'alkitābu, 'alkitāba, 'alkitābi). The genitive and accusative are not differentiated in the dual and in some plurals as well as in certain type of nouns. The case system has entirely disappeared in Colloquial Arabic.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine. The latter is generally marked by the suffix -at, placed before the case marker, though certain feminine words are unmarked (those with feminine natural gender, paired parts of the body, natural elements and heavenly bodies).

-

•number: singular, dual, plural. The singular is unmarked, the dual is marked by the suffix -āni, and the plural can also be marked by a suffix or, more frequently, involves a complete change of the vowels of the word (broken plural).

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

Personal pronouns distinguish number (singular, dual, plural) and gender (masculine, feminine) except for the first person and the dual. They have independent and enclitic forms. Independent forms exist only in the nominative. The enclitics are used as possessive markers and object pronouns as well as after prepositions. Dual pronouns no longer exist in Colloquial Arabic.

-

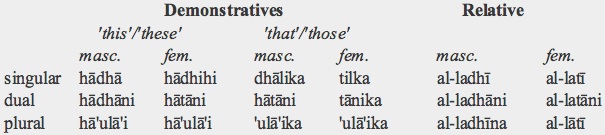

Demonstrative and relative pronouns also differentiate between masculine and feminine:

-

The interrogative pronouns are: man ('who?') and mā/mādhā ('what?'). Other interrogative words: 'ayy ('what/which?'), limādhā ('why?'), matā ('when?'), 'ayna ('where?'), kayfa ('how?'), kam ('how many?'). Yes-no questions are introduced by the interrogative particle hal placed at the beginning of the sentence.

-

Verbal. The main categories of the verb, like person, mood and tense-aspect, are marked by prefixes and suffixes.

-

•person and number: 1 s, 2 ms, 2 fs, 3 ms, 3 fs; 2 d, 3 dm, 3 df; 1 p, 2 mp, 2 fp, 3 mp, 3 fp. Conjugations distinguish, like the personal pronouns, person, gender (masculine, feminine) and number (singular, dual and plural). In the 3rd person dual there are different verb forms for masculine and feminine subjects albeit the corresponding personal pronoun is common to both genders. Dual verbal forms have disappeared in Colloquial Arabic.

-

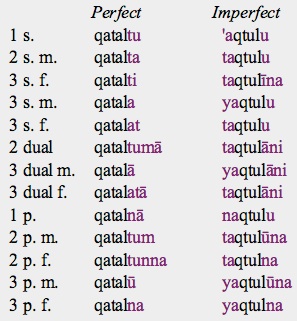

•tense: past or perfect and non-past or imperfect are the two basic tense-aspects. The perfect is formed by adding a single suffix to the perfect stem encoding person, gender and number. The imperfect is formed by adding prefixes to the imperfect stem (encoding person) and suffixes (encoding gender and number). The future tense is made by prefixing sa or sawfa to the imperfect. As an example, the conjugation of qatal ('to kill') is shown in the table.

-

root: qtl

-

perfect stem: qatal

-

imperfect stem: qtul

-

•mood: indicative, subjunctive, jussive, imperative.

-

The subjunctive is formed from the imperfect by replacing the final u with a and dropping the na/ni endings. The jussive drops the final u of the imperfect and the na/ni endings. The imperative has just five forms: 'uqtul (ms), 'uqtulī (fs), 'uqtulā (dual), 'uqtulū (m.p), 'uqtulna (f.p).

-

•voice and derivative conjugations: active, reflexive, passive, reciprocal, intensive, causative.

-

Besides the basic conjugation (Form I), there are nine derived conjugations. Form II conveys causativity or intensiveness, form III reciprocity, form IV causativity, form V is the passive of form II, form VI is the reflexive of form III, form VII is the passive or reflexive of form I, form VIII is the reflexive of form I (but in contrast to form VII can take a direct object), form IX is restricted to color or physical defects ('it turned red'), form X is the reflexive of form IV.

-

The stems of these forms are made by vowel changes in the basic stem or by adding prefixes (in form VIII an infix).

-

•non-finite forms: verbal nouns, active and passive participles. Each of the ten conjugations (forms I-X) has its own series of non finite verbals.

Syntax

The basic neutral order of Classical Arabic is Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) but Colloquial, and to some extent Modern Standard Arabic, have become SVO. The verb and the subject agree in number and gender except when the verb precedes the subject. Adjectives follow their head nouns agreeing with them in case, definiteness, gender and number (the last two with certain restrictions). Interrogatives are placed at the beginning of the sentence.

Lexicon

Early loanwords came mainly from Aramaic/Syriac and in smaller proportion from other Semitic languages like Akkadian, Hebrew and Ethiopic. Among Indo-European languages, Greek and Persian contributed many technical terms, the latter particularly in the domains of pharmacology, mineralogy and botany.

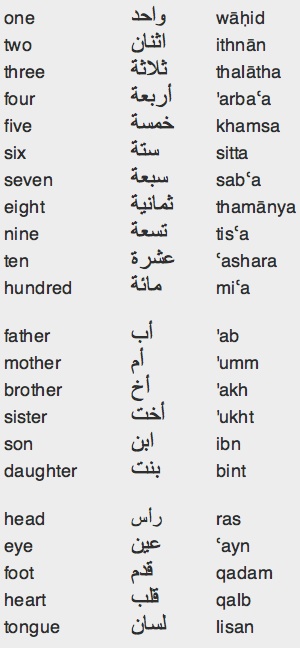

Basic Vocabulary

Key Literary Works

-

10th c. Saifiyyat. al-Mutanabbī (915-65)

-

Panegyrics celebrating the military victories of Sayf al-Dawla, ruler of northern Syria, to whose court al-Mutanabbī was attached. They are hyperbolic, baroque, powerful, imaginative, brilliant, liberating the traditional ode (qasidah) of some of its constraints and giving it a more personal voice.

-

c. 1000 Maqāmāt (Assemblies). al-Hamadhānī (969-1008)

-

Al-Hamadhānī was the creator of the maqāmah (plural maqāmāt), a literary form consisting in a sketch, a small scene, originally realistic, told mostly in rhymed prose. Of those he wrote, 52 are extant today. They are woven around two characters, the narrator and the main protagonist, a charlatan poet who seeks fortune without scruples.

-

11th c. Risālat al-ghufrān (Epistle of Forgiveness). al-Maʿarri (973-1057)

-

Written in prose, it tells about a sheikh who visits paradise and meets pre-Islamic poets who justify their graphic depictions of revelry and wine drinking. It has satiric and polemic overtones.

-

11th c. Luzūm mā lam yalzam (Unnecessary Necessity). al-Maʿarri (973-1057)

-

The title refers to some self-imposed rhyme restrictions on this poetic composition whose merits are, however, more in its freedom of thought and its rare anticonformism than in any formal achievement. These, usually short, poems reflect with skepticism on life and fate, on god and the next world, on the limitations of man…

-

c. 1100 Maqāmāt (Assemblies). al-Ḥarīrī (1054-1122)

-

Based on the work of al-Hamadhānī, these humorous stories strive for a more refined literary style than those of his precursor.

-

c. 1175 Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān (Alive, Son of Wakeful). Ibn Ṭufayl (1109-85)

-

A philosophical romance describing the development, educational and philosophical, of a man who lives his first fifty years in isolation on an uninhabited island.

8th-12th c. Alf laylah wa laylah (The Thousand and One Nights). Anonymous

-

A collection of oriental stories within a frame narrative, a patchwork of fairytales, legends, fables, romances and adventures, transmitted orally through many centuries with material added at different periods and places (India, Iran, Iraq, Egypt, Turkey).

-

11-12th c. Sīrat 'Antar ibn Shaddād (Romance of Antar). Anonymous

-

Not dissimilar to "The Thousand and One Nights" but more authentic at times, its chivalric hero undertakes many adventures in order to be able to marry his cousin Ablah, traversing the Middle East and North Africa to reach Europe where he enters in contact with kings and emperors. It shows considerable knowledge of Persian customs and Crusader's life.

-

1325-49 Riḥlah (Travels). Ibn Battuta

-

One of the greatest travelers of all times, his journey started in North Africa, and from there he went to the Middle East, Asia Minor and the Russian steppes, Iran and South Asia staying fourteen years in India where he served the Tughluq dynasty. Afterwards, he proceeded to South East Asia and, perhaps China. He was not a scholar but his entertaining accounts are a major source for the political and cultural history of some of these regions.

-

1933 Ahl al-kahf (The People of the Cave). Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm

-

Al-Ḥakīm was the founder of contemporary Egyptian drama who won fame with this play based on a Christian and Quranic legend. Several people take refuge in a cave fleeing from the Roman persecution of Christians. They sleep for three-hundred years to wake up in a very different world. They try to renew their lives but they fail and are driven back once more to the cavern.

-

1955 al-Sudd (The Dam). al-Mas‘adi

-

A symbolic and allegoric novel, written in the form of a play, centered on the conflict between a determined man and a goddess of an institutionalized religion that deprives the people from initiative and creativity. He decides to build a dam to improve life in the valley but it is in danger of being destroyed…

-

1956–57 Al-Thulāthiyyah (The Cairo Trilogy). Naguib Mahfouz

-

This trilogy, his major work, depicts the lives of three generations of a family in Cairo from the beginning up to the middle of the 20th century, providing a penetrating overview of Egyptian society.

-

1950–90 Short stories. Yusuf Idris

-

This Egyptian political activist portrays poor people with economy of words and make his characters speak in colloquial, everyday, language.

-

1987 Sahirtu minhu al-layali (Sleepless Nights). ‘Ali al-Duaji

-

A posthumous collection of short stories, by a Tunisian writer, dealing with ordinary people struggling in an unjust society. Resorting to the colloquial language in his dialogues and to a variety of registers and forms, he blends stark realism with humor.

-

2008 Taksīr Rukab (Breaking Knees). Zakaria Tamer

-

A collection of short stories, by a Syrian writer, about authority and repression, political, religious and sexual, touching many taboo subjects in the Arab world like the sexuality of women.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-A Grammar of the Arabic Language. W. Wright. Cambridge University Press (1955).

-

-L’Arabe classique: esquisse d’une structure linguistique. H. Fleisch. Imprimerie Catholique (1956).

-

-Introduction à l’Arabe Moderne. C. Pellat. Adrien-Maisonneuve (1956).

-

-The Arabic Language. K. Versteegh. Edinburgh University Press (2001).

-

-'Arabic'. A. S. Kaye. In The World's Major Languages, 560-577. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-A Linguistic History of Arabic. J. Owens. Oxford University Press (2006).

Arabic

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania