An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Overview. The Semitic languages are among the oldest recorded. Some of them are associated with ancient civilizations: the powerful Assyrian and Babylonian empires, the Phoenician merchants that spread all over the Mediterranean and transmitted the alphabet to the Greeks, the Hebrews and their monotheistic religion that influenced profoundly Christianity and Islam, the Axumite empire of Ethiopia and their Ge'ez tongue, the Arabs that excelled in architecture and sciences.

Today, many Semitic languages are extinct but Arabic has become a world language, Hebrew after ceasing to be spoken was revived in modern times and is now the language of Israel, and some Ethiopic languages, like Amharic and Tigre, are thriving.

Semitic is the major branch of the Afro-Asiatic phylum. Proto-Afro-Asiatic is assumed to have originated in Africa from where the ancestors of the Semites would have migrated into the Arabian Peninsula and further into the Near East. There, Semitic languages split and later some populations migrated back to Africa crossing the Red Sea from South Arabia, originating the Ethiopic Semitic languages after suffering a considerable influence from Cushitic speakers. The spread of Arabic into North Africa is a much later phenomenon.

Distribution.

Semitic languages predominate in North Africa, the Horn of Africa and the Middle East (Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, the Syro-Palestinian region). Significant minorities of Semitic speakers exist in Iran and Turkey, in western Europe and North America.

External Classification. Semitic languages constitute one of six branches (or families) of the Afro-Asiatic phylum. Within Afro-Asiatic, they are quite close to the Berber and Ancient Egyptian branches and less so to Chadic, Cushitic and Omotic.

Internal Classification. Semitic is divided into a small East Semitic branch (now extinct) and a much larger Western Semitic branch.

-

A.East Semitic (extinct): Akkadian (Assyrian, Babylonian) and Eblaite. Akkadian was spoken in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and Eblaite in Syria. Assyrian and Babylonian were northern and southern dialects of Akkadian.

-

B. West Semitic is divided into Southern, Central and Northern groups:

-

1. South Semitic

-

-

a)Epigraphic South Arabian (extinct). Spoken, formerly, in the southern half of the Arabian peninsula.

-

b)Modern South Arabian is represented by half a dozen languages spoken by about 200,000 people in Yemen and Oman. Mehri and Soqotri are the major ones, followed by Shehri, Harsusi and Bathari which have a few hundred speakers each.

-

c)Ethiopian is divided into North and South Ethiopic, the latter further subdivided into Transversal and Outer:

-

•North Ethiopic: Ge'ez (extinct), Tigrinya (Ethiopia, Eritrea), Tigré (Eritrea, Sudan).

-

•South Ethiopic:

-

I.Transversal South Ethiopic includes two large languages, Amharic and Selti, and a few minor ones: Argobba, Harari and Zay.

-

II. Outer South Ethiopic:

-

n-group: Gafat (extinct) and Soddo (or Kistane).

-

tt-group: includes Muher and Western Gurage languages (Ezha-Gumer-Chaha-Gura cluster and the Gyeto-Ennemor-Endegen-Endar cluster) spoken by one million people in total.

-

2. Central Semitic

-

-

a)North Arabian: Old North Arabian (extinct), Arabic, Maltese.

-

b)Northwest Semitic

-

-

•Aramaic dialects: most of them extinct though some, grouped into Neo-Aramaic, are still spoken in the Middle East (Modern Syriac, Modern Mandaic, etc).

-

•Canaanite languages: Canaanite, Ugaritic, Ammonite, Amorite, Moabite, Edomite, and Phoenician, all of them extinct, plus Hebrew.

Note: Some authors divide Central Semitic differently, into two co-equal branches: Aramaic + South-Central Semitic (the latter divided into North Arabian + Canaanite).

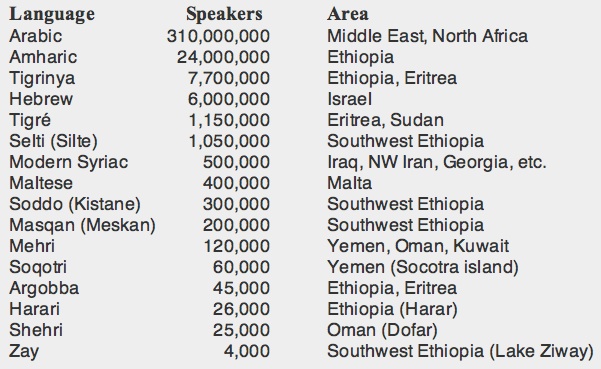

Major Languages and Speakers. There are more than 351 million native speakers of Semitic languages. The main ones are:

SHARED FEATURES

-

✦ Phonology

-

-The original Proto-Semitic vowel system consisted of a, i and u, each of them short and long. It is preserved without modification in Classical Arabic.

-

-Consonants may exhibit a three-way contrast at the same point of articulation: voiceless, voiced and 'emphatic'. The latter are pronounced pharyngealised in Arabic or glottalized (called ejectives) in Ethiopian and Modern South Arabian. In Modern Hebrew the emphatics have been lost.

-

-Arabic, Tigrinya and Tigré have preserved the two original Semitic pharyngeal fricatives (voiceless and voiced).

-

-In Aramaic, Hebrew and several Ethiopian languages, a process of spirantisation (conversion of stops into affricates or fricatives) took place, leading to alternations in different forms of the same root. For example, in Modern Hebrew [p] alternates with [f], [b] with [v] and [k] with [x] in some environments.

-

✦ Morphology

-

Nominal

-

-The older languages (Akkadian, Classical Arabic, Phoenician) have a rudimentary case system consisting of nominative, accusative and genitive; the last two only differentiated in the singular. In modern languages, cases have been largely replaced by prepositions or postpositions.

-

-Semitic distinguishes masculine and feminine genders in nouns and pronouns (except in the first person). The feminine is marked in most languages with the suffix t.

-

-Singular, dual and plural numbers are distinguished in some languages. The dual is alive in Arabic, is marginal in Akkadian and Hebrew and has been lost in Ethiopian. The formation of plurals is usually complex, involving vowel changes in the stem (‘broken plural’) and/or a suffix marker accompanied, sometimes, by reduplication.

-

-Nouns can be in an absolute or in a construct state. The construct state denotes a genitival relationship (belonging to). The qualified or possessed noun (which may have some phonetic change at its end) comes first and the qualifying after (except in modern Ethiopian).

-

-There are three basic sets of personal pronouns: independent ones for subject and predicate functions, possessive pronouns suffixed to nouns or to prepositions and object pronouns attached to verbs.

-

Verbal

-

-The verb occupies a central position in Semitic languages, and many nouns derive from them. Verbs have bi-, tri- or tetraconsonantal lexical roots to which vowels add grammatical information (‘root and pattern system’). For this reason, these languages do not write their vowels, a feature that makes linguistic comparisons and reconstructions difficult. Further grammatical information is provided by prefixes and suffixes.

-

-There are two basic conjugations. The perfective (indicating a completed action and usually a past tense) uses suffixes to indicate person, gender and number. The imperfective or non-past (incomplete action with present or future sense) employs prefixes and/or suffixes to mark person, gender and number.

-

-By means of prefixes, changes in the root vowels and reduplication, derivative verbs may be formed that express intensive (or repetitive), causative, reflexive or passive meanings.

-

✦ Syntax

-

-Proto-Semitic seems to have had a Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) syntactic order which is, more or less, preserved in the old languages (Classical Arabic, Biblical Hebrew and Ge'ez). Later, word order becomes SVO in Colloquial Arabic and Modern Hebrew, or SOV in the modern Ethiopian languages (probably under the influence of neighboring Cushitic).

-

-When adjectives are used attributively, they agree with the noun they qualify in gender, number, case and definiteness. They follow their noun except in modern Ethiopian. Demonstratives also follow the noun (except in Arabic and in some modern Ethiopian languages) but numerals most often precede it.

-

-There are usually two genitive constructions, one using the construct state, the other employing a genitive particle. Except in modern Ethiopian, the order is always possessed-possessor.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Semitic Languages'. R. Hetzron & A. S. Kaye. In The World's Major Languages, 551-559. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-The Semitic Languages. R. Hetzron (ed). Routledge (2006).

-

-Grammaire Comparée des Langues Sémitiques: Éléments de phonétique, de morphologie et de syntaxe. J.-C Haelewyck. Éditions Safran (2006).

-

-Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar. E. Lipiński. Peeters (2001).

-

-An Introduction to the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages, Phonology and Morphology. S. Moscati (ed). O. Harrassowitz (1964).

Semitic Languages

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania