An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Afro-Asiatic, Semitic, Northwest Semitic, Canaanite. Hebrew is quite closely related to other (extinct) Canaanite languages like Phoenician, Moabite, Ammonite and Edomite.

Overview. Hebrew was the language of ancient Israel and of the Jewish Bible. In medieval times it ceased to be spoken but remained alive as a liturgical, epistolary and literary medium. In the 19th century, Hebrew was revived as an oral means of communication and later became the official language of the modern state of Israel. Modern Hebrew has been deeply influenced, especially in its phonology and vocabulary, by European languages.

Distribution and Speakers. Hebrew is spoken by more than 6 million people worldwide. About 75 % of the population of Israel (5. 8 million) speaks Hebrew as a first language while many Arabs within the country speak it as a second language. In the Americas, Hebrew is spoken by 210,000 in USA and 65,000 in Canada. It is also spoken in some European countries and in Australia.

Status. Hebrew ceased to be a regularly spoken language by the 4th century CE, but survived as a liturgical and literary language. It was revived in the 1880s and now is, with Arabic, the official language of Israel.

Varieties. There are three main dialects: Ashkenazi (Eastern European), Sephardi (Southwestern European) and Mizrahi (Middle Eastern). In Israel, Standard Hebrew (Modern Israeli Hebrew) is dominant.

Periods

1000 BCE-100 CE. Biblical Hebrew. It may be subdivided into Early Biblical, Late Biblical and Dead Sea Scroll Hebrew:

-

•Early Biblical Hebrew (10th-6th c. BCE) is represented in the Pentateuch, Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings and the prophetic books.

-

•Late Biblical Hebrew (6th-4th c. BCE) is represented in Chronicles, Song of Songs, Esther, etc.

-

•Dead Sea Scroll Hebrew (3th c. BCE-1st CE) is evidenced in the ancient manuscripts discovered in desert caves and ancient ruins of Judaea of which the best-preserved are those found at Qumrān.

1st -4th CE. Mishnaic Hebrew. Represented in the Talmud.

6th-15th c. Medieval Hebrew. Hebrew ceased to be an spoken language but developed as a vehicle for a rich literature in Europe and in the Near East, perduring as the medium for Jewish ritual and religion, philosophy and letters. In the following interim period, Hebrew declined as a literary language being restricted to religious activities and documents.

19th c. CE-present. Modern Hebrew. Hebrew was revived, in a modified form, as an spoken language mainly due to the efforts of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda to satisfy the needs of Jewish immigrants arriving to Palestine from the 19th century. With the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 it was adopted as the official language of the country. Modern Hebrew exhibits some European language features incorporated onto its basic Semitic core.

Oldest Documents. Apart from the Hebrew Bible, composed in the course of many centuries during the last millenium BCE, a number of ancient inscriptions have survived:

c. 900 BCE. The Gezer Calendar, a brief inscription in limestone specifying the agricultural tasks to be performed in every month or bimester of the year.

c. 800 BCE. Votive inscriptions from Kuntilet Arjud, a small religious centre in the Sinai Desert.

8th c. BCE. Ostraca (broken pieces o pottery) from Samaria accounting for oil and wine delivered to the town.

late 8th c. BCE. The Siloam inscription, carved inside a water tunnel of Jerusalem, telling how the tunnel was excavated by two crews working from opposite directions.

late 7th c. BCE. The Arad inscriptions, most of them written in ostraca with black ink, giving a vivid impression of daily life in a small fortress of the Negev desert.

c. 590 BCE. The Lachish letters, written in ostraca with black ink, addressed to a military commander by one of his subordinates.

Phonology (Modern Hebrew).

Vowels (5): i, u, e, o, a. There is no contrast between short and long vowels. Vowels are not usually written though some of them may be represented by semivowels sings.

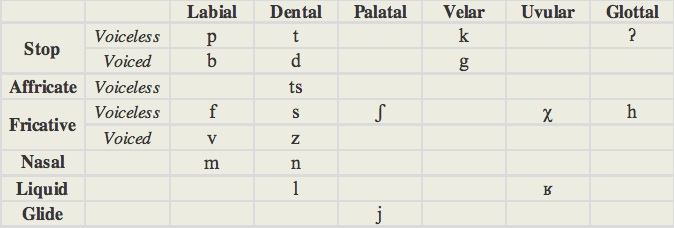

Consonants (20). The pronunciation of Modern Hebrew consonants has been influenced by Yiddish. The 'emphatic stops' and pharyngeal fricatives of North West Semitic no longer exist in Modern Hebrew. Biblical Hebrew had three 'emphatic' consonants, as the Hebrew script reveals, but nowadays they are pronounced without emphasis: ṭ is pronounced t, tṣ is pronounced ts, and q is pronounced k. The voiced pharyngeal fricative represented by the letter áyin (see script below) is no longer pronounced and the voiceless pharyngeal fricative represented by the letter ḥet became an uvular fricative. The semivowel w has merged with the fricative v.

Stress: it generally falls on the last syllable, otherwise on the penultimate.

Script and Orthography

The Hebrew alphabet is a consonantal script read from right to left, composed of 22 letters. It derives from the Phoenician alphabet which evolved into an Aramaic script and later into the Jewish ‘square’ script that is the standard printed form. Five letters have special word-final forms.

Note that vav and yod may represent either a semivowel or a vowel.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Nouns have independent or dependent forms. Dependent nouns are those that are part of a nominal compound or have a suffix attached to them; they usually experience internal vowel changes and changes at the end of the word. Nouns are marked for gender, number, definiteness and possession.

-

•case: nouns do not bear case markings except for the particle et that precedes a definite direct object.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine. The gender of animate beings reflects their sex, though gender assignment to animal species and plants is arbitrary. Gender of inanimate things is also arbitrary and unpredictable.

-

Masculine singular nouns are unmarked for gender and don't have a characteristic ending but plural ones usually end in -im. Most singular feminine nouns end in -ah or -t, and most plural ones end in -ot.

-

melekh ('king') → mlakim ('kings')

-

malkah ('queen') → mlakot ('queens')

-

Some feminine nouns lack the usual feminine ending, like: ’erets ('land'), ʿir ('city'), ’eben ('stone'), ozen ('ear').

-

Some animate nouns have completely different words for masculine and feminine:

-

’av ('father') → ’em ('mother')

-

bʿal ('husband') → ’ishah ('wife')

-

shor ('bull') → parah ('cow')

-

•number: singular, dual, plural. Many masculine nouns form the plural with the suffix -im, though some adopt endings similar to feminine plurals. Most feminine plurals are made with the suffix -ot though some adopt the masculine ending -im. Some nouns experience consonantal changes in the stem when they become plural.

-

a) masculine nouns with feminine-like plural:

-

reḥov ('street') → reḥovot ('streets')

-

’av ('father') → ’avot ('fathers')

-

shulḥan ('table') → shulḥanot ('tables')

-

b) feminine nouns with masculine-like plural:

-

ʿir ('city') → ʿarim ('cities')

-

shanah ('year') → shanim ('year')

-

milah ('word') → milim ('words')

-

c) plural with consonant change in the stem:

-

’ish ('man') →’anashim ('men')

-

’ishah ('woman') → nashim ('women')

-

The dual number is restricted to time units (weeks, months, etc), symmetrical parts of the body (eyes, hands, legs, etc), and garments and articles that come in pairs (socks, trousers, glasses, etc); it is marked by the suffix -aym for both genders. Time units have three forms, singular, dual and plural, but the other nouns of this group don't have a plural form (if required it is made by adding the word "pairs").

-

ḥodesh ('month') → ḥadashaym ('two months') → ḥadashim ('months')

-

’ozen ('ear') → ’aznaym ('a pair of ears')

-

gerev ('sock') → grevaym ('a pair of socks')

-

Three words are always dual in Hebrew: shamaym ('skies'), mitsraym ('Egypt'), maym ('waters').

-

•definiteness: Hebrew has a definite article (ha) that is prefixed to common nouns. Proper nouns are definite by nature and don't require the definite article. The attachment of a possesive pronoun suffix to a noun makes it also definite (the definite article is not then required). Excepting proper nouns, nouns without the definite article or a possessive pronominal suffix attached to them are indefinite.

-

•states: absolute state, construct state. Nouns have a construct state, called smikhut, to denote the relationship "belonging to". The qualified noun comes first and the qualifying after, sometimes they are joined by a hyphen. The first noun is frequently modified by a special ending. In modern speech, the use of the construct is sometimes interchangeable with the preposition shel, meaning "of ".

-

a) without modification of the first noun:

-

sof shabuʿa ('weekend')

-

end week

-

-

’erets israel ('land of Israel)

-

land Israel

-

b) with modification of the first noun:

-

‘aruḥah ('meal') > aruḥat-erev ('evening meal')

-

-

salim ('baskets') > salei-leḥem ('bread baskets')

-

To make a construct phrase plural only the first member changes; the other remains in the singular.

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

Personal pronouns are masculine or feminine though for the first person there is only just one, common gender, pronoun. They can refer to persons, animals, objects, events or ideas. They can be independent words or they can be prefixed or suffixed to other words. They can function as subject, direct object or indirect object. The feminine plural pronouns are rather formal and in everyday speech the masculine forms are used for both genders.

-

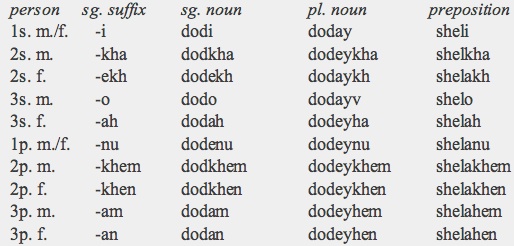

Possessive pronouns are formed by the attachment of pronoun suffixes to nouns or to the preposition shel (‘of’). In the examples the possessive suffixes are attached to dod (‘uncle’).

-

If the noun possessed is plural, -ay-/-ey- precede the possessive suffix e.g. dodi is ‘my uncle’ and doday ‘my uncles’.

-

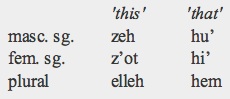

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish two deictic degrees (‘this/that’). They precede their nouns and agree with them in gender and number. The remote pronoun forms (‘that, those’) are identical to the 3rd. person pronouns.

-

The interrogative pronouns are mi (‘who?’) and mah (‘what?’).

-

Several words can function as indefinite pronouns but often they can be omitted, using instead a subjectless verb conjugated in the 3rd singular.

-

Relative clauses are obligatorily introduced by the particle she.

-

Verbal. Verbs are based on a consonantal root which is more often triconsonantal or, sometimes, biconsonantal. Hebrew roots are not actual words but just a sequence of consonants. When a vowel pattern is added to a root it becomes a stem. To the verb stem, conjugation markers (prefixes and/or suffixes) are added to indicate tense or mood, person, gender and number, often accompanied by a change in the vowel stem. The citation form of a verb (how it is listed in a dictionary) is usually the past tense, third person singular.

-

•person and number: 1 s, 2 ms, 2 fs, 3 ms, 3 fs; 1 p, 2 mp, 2 fp, 3 mp, 3 fp.

-

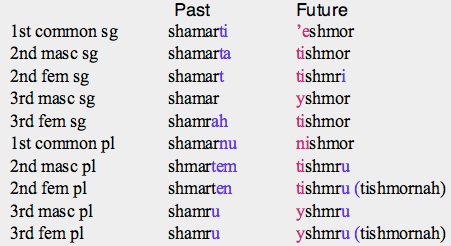

•tense: present, past, future in Modern Hebrew. The present tense is marked for gender and number but not for person. Thus, it has only four forms. The present tense marker is the vowel o. As an example, the present of shamar (‘to guard’) is shown in the table (gender and number endings in blue).

-

In contrast, the past and future are marked for person, gender and number. The tense marker for the past is zero. The tense marker for the future is a prefix (shown in red) while person and number are marked by a combination of prefix and suffix.

-

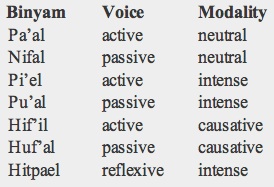

•derivative conjugations: there are seven derivational classes called binyamim (‘buildings’). From a root more than one verb can be formed in different binyanim. These different verbs are usually related in meaning, typically differing in voice, valency, intensity (repeated action), aspect or a combination of these features. In fact, in Modern Hebrew, the binyamin may express a variety of functions that not necessarily correspond with the traditional classification shown in the table.

-

The Pa’al conjugation is the one exemplified above.

-

•mood: indicative, imperative, (jussive), (cohortative).

-

Verbs in five of the binyanim have an imperative (the passive pu'al and hu'fal don't have one). In colloquial Hebrew, an affirmative imperative is expressed by the future, in more formal Hebrew by dropping the prefix from the future. The negative future is formed by using the particle al with the future tense. Finally, a very small number of expressions include verbs in the jussive mood which is an extension of the imperative into the 3rd person. The cohortative is a form of imperative with a future connotation used in Biblical and Modern formal Hebrew in the first person only.

-

•voice: active, passive, reflexive. They are represented in the binyanim as shown above.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive construct, infinitive absolute, active and passive participles.

-

Like the imperative, the passive pu'al and ho'fal binyanim don't have an infinitive. The infinitive construct is similar to the English infinitive (sometimes it can be also used as a gerund); the infinitive absolute occurs mostly in Biblical Hebrew and is used for emphasis, to give and emphatic command or as an abstract noun.

Syntax

Generally, word order is SVO (Subject-Verb-Object), but when the object is a question-word it is moved to the front of the sentence. The Bible and other religious texts are predominantly written in VSO (Verb-Subject-Object) word order. Indefinite subjects are often postponed. Indirect objects require prepositions and definite direct objects are introduced by the particle et. The verb to be is omitted in the present tense. Adjectives come after the noun and agree in gender, number and definiteness with the noun they modify. Quantity words precede their nouns (with a few exceptions) and are invariable.

Basic Vocabulary

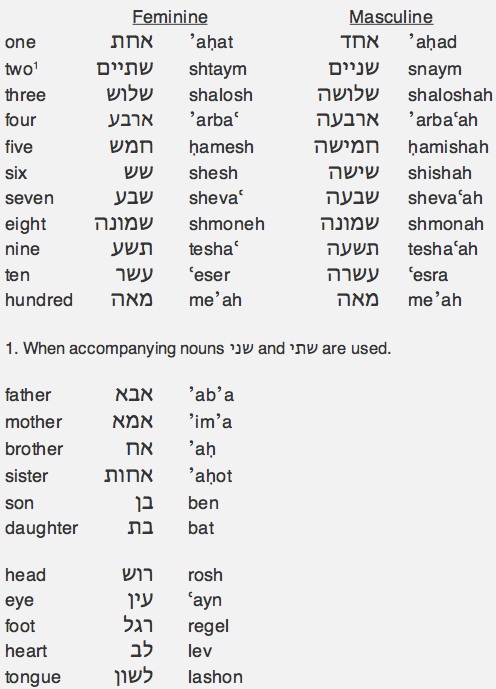

Hebrew numbers can be masculine or feminine. The basic form (that used for counting) is the feminine. If a number is followed by a noun it agrees with it in gender. Feminine numbers have, paradoxically, masculine endings and vice versa.

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

Further Reading

-

-A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew. J. Blau. Otto Harrassowitz (1976).

-

-Traité de Grammaire Hébraïque. M. Lambert. Gerstenberg (1972).

-

-A Reference Grammar of Modern Hebrew. E. A. Coffin & S. Bolozky. Cambridge University Press (2005).

-

-'Hebrew'. R. Hetzron (revised by A. S. Kaye). In The World's Major Languages, 578-593. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-A History of the Hebrew Language. E. Y. Kutscher. The Magnes Press; E.J. Brill (1982).

-

-Ancient Hebrew Research Center. J. A. Benner. Available online at: http://www.ancient-hebrew.org

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Hebrew

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania