An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification. Ancient Egyptian on its own constitutes one of the six branches in which the Afro-Asiatic languages are divided. It is quite closely related to Semitic and Berber branches and more distantly to Cushitic and Chadic.

Overview. Egyptian is one of the oldest documented languages and the one which has the longest record, spanning more than four millennia. It was spoken by the ancient Egyptians who created a unique and long-lasting civilization, immediately recognizable for its architecture, art, religion and literature. They contributed to the invention of writing devising, shortly after the Sumerians (or perhaps simultaneously), a hieroglyphic system of great originality and beauty.

Distribution. Formerly, in the Nile valley in Egypt.

Status. Extinct. Documented between 3000 BCE and 1300 CE.

Periods.

3000-2000 BCE. Old Egyptian: the first continuous texts appear, preceded by brief inscriptions. It is found in the inscriptions of the Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period (royal Pyramid Texts and private autobiographies in tombs).

2000-1300 BCE. Middle Egyptian: the language of the Middle Kingdom and of the New Kingdom up to the end of the 18th dynasty. Structurally similar to Old Egyptian, it is considered the classical stage of the language, serving as a vehicle for literary (instructions, tales) and religious (hymns, Coffin Texts) compositions.

1300-700 BCE. Late Egyptian: the language of the New Kingdom, from the 19th dynasty, and Third Intermediate Period. It is grammatically quite different from Old and Middle Egyptian. The most important Late Egyptian documents are the secular ones of the Ramesside bureaucracy but there are also wisdom and narrative texts.

700 BCE-400 CE. Demotic: the language of the Late Period, quite similar to Late Egyptian but written in the cursive Demotic script.

400-1300 CE. Coptic: the final stage of the Egyptian language, prevalent during the Christian period. It was written in the Coptic script which, in contrast to the previous ones, represented the vowels. It had two dialects: Sahidic was a literary dialect of Thebes or Memphis and Bohairic was the dialect of the West Delta. Coptic is still in use in the ritual of the Egyptian Christian Church.

Oldest Documents. The earliest Egyptian documents appeared in the Early Dynastic Period which comprises the three first dynasties. They include artifacts, specially vessels, carrying the name of the king accompanied sometimes by a short inscription, seal impressions found in royal tombs listing the first kings, year labels recording the most important events of the year, lists of offerings and rock-cut inscriptions in the desertic regions.

Phonology

Vowels. The knowledge of Egyptian vowels is very incomplete though they can be deduced to some extent from Coptic. Other sources are ancient Greek, Assyrian and Babylonian texts in which there are fully vocalized transcriptions of Egyptian words.

For the earlier periods of Egyptian, a simple system of three vowels, inherited from Proto-Afro-Asiatic, can be posited. Each vowel had short and long varieties but in most cases the contrast between them was not phonemic:

-

front: i, i:

-

central: a, a:

-

back: u, u:

-

In Later Egyptian, the vowels e, ə (schwa) and o were added.

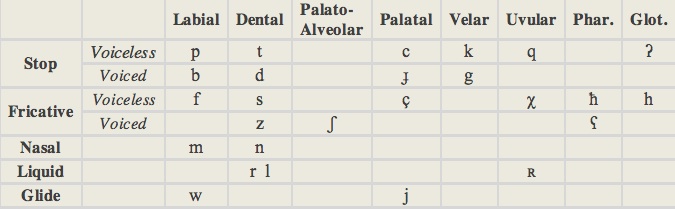

Consonants (26). Egyptian consonants included several articulated at the back, namely uvular and glotal stops, uvular, pharyngeal and glottal fricatives and a liquid uvular.

Stress. It falls either on the last syllable or on the penultimate one.

Scripts

-

a)Hieroglyphic

-

Used in religious and monumental inscriptions, it is a mixed system formed by:

-

•logograms (conveying meaning) +

-

•phonograms (conveying sound) +

-

•determinatives (which indicate the exact meaning of the word).

-

The writing was from right to left (only in certain cases from left to right), in columns (from top to bottom) or in horizontal lines. Hieroglyphs were carved on stone or wood and inscribed into imaginary squares or rectangles.

-

b)Hieratic

-

Hieratic ('priestly', from Greek hieratikos) is an adaptation of Hieroglyphic with its signs simplified for handwriting. It was written on sheets of papyrus and ostraca, in black ink applied with a brush. The writing was from right to left and in columns or horizontal lines.

-

It was used in administrative, literary, religious and scientific documents (the oldest are state records of the 4th Dynasty). Demotic replaced it for most purposes, in c. 600 BCE, and from that time on Hieratic was used for religious documents only (the latest are papyri from the 3rd c. CE).

-

c)Demotic

-

Demotic ('popular', from Greek demotika) was also a cursive script. Written in horizontal lines from right to left on papyri and ostraca, it was used in legal, administrative and commercial documents. From the Ptolomean Period there are also scientific, literary and religious texts (an example is the Rosetta Stone). The latest inscription was found in the Temple of Philae (450 CE).

-

d)Coptic

-

Coptic ('Egyptian', from Greek aiguptius and Arabic gubti) is an alphabetic script, in which vowels are notated, consisting of 24 letters of the Greek alphabet plus 6 characters from Demotic. It was written from left to right in horizontal lines with no gaps between words and almost no punctuation. Ink and reed pen on papyri and ostraca, wooden tablets, parchment and paper were used for writing. The earliest documents are magical texts dating back to the end of the 1st c. CE. Later, it became the language of Christian Egypt.

Morphology (Middle Egyptian)

Ancient Egyptian words are based on lexical roots formed by one to four consonants (most are biconsonantal and triconsonantal). The consonantal root is combined with vowels or semivowels to form the stem which determines the functional category of the word. Finally, affixes are added to the stem to convey grammatical functions such as gender, number, tense, aspect and voice transforming it into an actual word.

-

Nominal. Adjectives agree in gender and number with the noun. There are no articles.

-

•case: Ancient Egyptian, in contrast to most Afro-Asiatic languages has no case endings.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine. The masculine is unmarked, the feminine is marked by -t preceded by a vowel.

-

•number: singular, dual, plural. Plurality is usually marked by adding the suffix -w/-aw combined with a change in the vowel pattern of the stem. The latter process, called 'broken plural', is common in Afro-Asiatic languages. Many feminine words do not have a plural form, though some feminine plurals are marked with the suffix -wt.

-

The dual number was limited to parts of the human body occurring in pairs and related words; it was marked with the semivocalic suffix -y added to the plural of masculine nouns or to the singular of feminine nouns.

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

Egyptian has three sets of personal pronouns: suffix, enclitic and independent. Suffix pronouns are attached to nouns to indicate possession, to prepositions as a complement and to verbal forms to indicate the subject. Enclitic (or dependent) pronouns are employed to mark the object of transitive verbs and the subject of adjectival sentences; they only have singular forms. Independent pronouns function as subject of nominal sentences.

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish two deictic degrees (‘this/that’) but not gender and number in early Egyptian; adjective demonstratives were different from pronouns and distinguished gender and number. In later stages of the language adjectives and demonstrative pronouns have three forms (masculine singular, feminine singular and plural).

-

Verbal. Most verbal roots have two consonants, in contrast with Semitic ones that usually have three. A conjugated verb is composed of the verbal stem, derived from the lexical root, followed by a tense/aspect marker and a suffix pronoun. Verbal forms combine tense and aspect which depend on the syntactic context; in the initial position of a phrase the verb usually indicates tense but in non-initial position (once a time frame has been established) it indicates aspect. Mood also depends on context.

-

•person and number: 1 s, 2 ms, 2 fs, 3 ms, 3 fs; 1 dual, 2 dual 3 dual; 1 p, 2 p, 3 p. The Egyptian verb distinguishes gender in the second and third persons of the singular.

-

•tense: past, non-past. Apart from these narrative tenses, Ancient Egyptian had an stative tense to express the result of a verbal action. The simple past is marked by adding the suffix -n after the stem followed by a pronominal suffix or a nominal subject. The present is unmarked.

-

•aspect: imperfective, perfective.

-

•mood: indicative, imperative, subjunctive, prospective.

-

Apart from the indicative (a neutral mood), moods usually apply to future events. The prospective is the mood of wish and expectation (the equivalent of the Indo-European optative). The subjunctive expresses command and refers to the future. In Middle Egyptian the subjunctive and prospective merge but they are still distinguished by syntactical context.

-

•voice: active, passive (rare).

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, perfective participle (active and passive), imperfective participle (active and passive).

Syntax

Word order is quite strict and of the Verb-Subject-Object type. There is no distinction between main and subordinate clauses. Adjectives follow their nouns. Like many Semitic languages, Ancient Egyptian has a construct state where a direct genitive relationship is expressed by the apposition of two nouns.

Basic Vocabulary

one: wc (wuʕʕuw)

two: snwj (s'inuwway)

three: ḫmtw (χamtaw)

four: jfdw (yifdaw)

five: djw ('di:jaw)

six: sjsw ('saʔsaw)

seven: sfḫw ('safχaw)

eight: ḫmnw (χa'ma:naw)

nine: psḏw (pi'si:ɟaw)

ten: mḏw (mu:ɟaw)

hundred: št (ʃit)

man: zj

woman: zjt

mother: mwt

brother: sn

sister: snt

son: za

head: tp

face: ḫr

hair: šnj

ear: msḏr

eye: irt

foot: rd

heart: lb

house: pr

tree: xt

Literature

a) Old Kingdom

-

Pyramid Texts

-

Engraved inside the royal pyramids of the 5th and 6th dynasties in Saqqara, they consist of incantations to promote the resurrection of the deceased king and his ascent to the sky to be in the company of the immortal gods.

-

The Autobiography of Harkhuf

-

Harkhuf was a distinguished official who served two kings and became governor of Upper Egypt. His autobiography, carved in his tomb, contains an account of his four expeditions to Nubia (a valuable source for the relations between Egypt and Nubia in this early period), a standard catalogue of his virtues, and prayers for offerings. It also includes the text of a letter received from the young king Pepi II.

-

Instructions of Ptahhotep

-

It belongs to the Wisdom literature genre and consists of the instructions transmitted by the vizier Ptahhotep expounded in thirty seven maxims framed by a prologue and an epilogue. The ideal man has to be kind, generous just and truthful.

b) First Intermediate Period

-

Instructions addressed to King Merikare

-

These are the instructions of an old king (whose name has been lost) to his son Merikare, a testament which is also a sort of treatise on kingship.

-

c)Middle Kingdom

-

The Prophecies of Neferti

-

This work is an attempt to glorify the king Amenemhet I of the Middle Kingdom by the fictional device of transposing the sage Neferti to the court of the king Snefru of the Old Kingdom where he "prophesies" a period of civil war which will end with the coronation of Amenemenhet.

-

The Instruction of King Amenemhet I for his son Sesostris I

-

Written after the assassination of Amenemhet, the deceased king transmits his instructions to his son. His violent death is alluded in a veiled manner and the tone is bitter, the father advising his son not to trust men.

-

The Dispute between a Man and his Ba

-

A man disappointed with life yearns for death. Tired of his complaints, his ba or soul threatens to abandon him making his resurrection in the otherworld impossible. It tells him about the sadness of the tomb and entreaties him to enjoy life.

-

The Song from the tomb of King Intef

-

The songs to the dead were called "Harper's Songs" because they were accompanied by the harp and sung at funerary banquets. The words of this famous song show skepticism about the existence of the afterlife.

-

The Story of Sinuhe

-

Considered the most accomplished literary work of the Middle Kingdom, it takes the form of an autobiography composed to be inscribed in a tomb. It is a plausible story, though not necessarily true, relating the flight of the official Sinuhe into Canaan after hearing about the death of Amenemhet, his life in exile and his eventual return to Egypt years later.

-

d)New Kingdom

-

The Book of the Dead

-

A compilation of spells used by the ancient Egyptians for the resurrection of the deceased persons and to help them attain bliss in the afterlife. This collection of magical texts (accompanied with illustrations) was written on sheets of papyrus and buried with its owner. Its final form was achieved in the Late Period (26th Dynasty).

-

Great Hymn to the Aten

-

Composed during the reign of Akhenaton, who altered radically, though briefly, the nature of Egyptian religion, this hymn celebrates the supreme and sole god Aten, the creator of the universe and everything it contains.

-

The Instruction of Amenemope

-

If in the Instructions of Ptahhotep the ideal man was peaceful, wealthy and generous, in this Instruction man has to be modest and self-controlled to be virtuous. Contemplation and endurance are more important than worldly success.

-

The Report of Wenamun

-

Written at the end of the 20th Dynasty, it is an account of a mission to Lebanon (actual or fictional) to get precious cedar timber for a ship which reveals the political decline of the Egyptian kingdom and the contempt of its neighbors.

e) Late Period

-

The Victory Stela of King Piye

-

This long inscription by the Nubian king Piye, the founder of the 26th dynasty, is the foremost historical one of the Late Period. In a very factual and vivid style he recounts his reconquest of Upper Egypt and conquest of Lower Egypt inspired and protected by the god Amun. He is portrayed as courageous, clever and forgiving.

-

Two Hymns to Khnum

-

Inscribed in the temple of Esna, they are a short morning hymn to awaken the god Khnum and a longer hymn to glorify Khnum as a creator who fashions men and women in his potter's wheel. Other creator gods are seen as manifestations of him.

-

The Stories of Setne Khamwas

-

These two fantastic stories, written in Demotic, are preserved in different papyri but their protagonist is in both Prince Khamwas, the fourth son of King Ramses II, who was known as a very learned sage and antiquarian. The first is about his search of a book of magic. The second tells his visit to the netherworld in which the good have a blessed existence and the sinners suffer many tortures.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-Ancient Egyptian. A Linguistic Introduction. A. Loprieno. Cambridge University Press (1995).

-

-Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. J. P. Allen. Cambridge University Press (2010).

-

-Reading the Past. Egyptian Hieroglyphs. W. V. Davies. British Museum Press (1992).

-

-'Egyptian'. In Ancient Scripts.com: a compendium of world-wide writing systems from prehistory to today. Lawrence Lo. Available online at: http://www.ancientscripts.com/egyptian.html

-

-Ancient Egyptian Literature. Vol. I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. M. Lichtheim. University of California Press (1973).

-

-Ancient Egyptian Literature. Vol. II: The New Kingdom. M. Lichtheim. University of California Press (1976).

-

-Ancient Egyptian Literature. Vol. III: The Late Period. M. Lichtheim. University of California Press (1980).

-

-Ancient Egyptian Language (Discussion List). Available online at: http://www.rostau.org.uk

Ancient Egyptian

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania