An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Name: Nederlands, Hollands. The variety of Dutch spoken in Belgium is frequently called Flemish (Vlaams).

Classification: Indo-European, Germanic, West Germanic. Dutch is closely related to Afrikaans (spoken in South Africa). It is also related to German, English and Frisian.

Overview. Dutch is a typical Germanic language. It derives from the Low Franconian dialects of the Western Franks, an ancient Germanic tribe who colonized the southern Netherlands around the fourth century CE, after the fall of the Roman Empire. Modern Dutch is in many basic aspects closer to German than to English but, like English, it has lost most of the Germanic noun morphology.

Distribution. Dutch is spoken in the Netherlands and northern Belgium (the dividing line with the French-speaking south passes just south of Brussels which is itself bilingual). There are also some Dutch speakers in neighboring France, and in former colonies, particularly in Suriname (in the north of South America) and Dutch Antilles (Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten). North America (Canada, USA) also harbors a substantial number of Dutch speakers.

Speakers. Around 23 million in the following countries:

Netherlands

Belgium

Suriname

Canada

USA

France

Australia

17,000,000

5,000,000

300,000

153,000

151,000

80,000

36,200

Status: Dutch is the official language of the Netherlands and one of the official languages of Belgium. It is also the official language of administration in Suriname and in the Dutch Antilles.

Varieties. Modern Standard Dutch is based on the dialect of Amsterdam.

Oldest Documents

8th c. CE. Annotations (known as Malberg Glosses) in a Latin text, the Lex Salica or Salic Law of the Franks.

9th c. CE. Wachtendonck Psalm Fragments are what has survived of a translation into Old Dutch of an Old High German psalm.

c. 1100 CE. Leiden Willeram, an adaptation made by a Dutch scribe of a High German paraphrase of the Song of Solomon.

12th c. CE. Poems composed by Heinrich von Veldeke are the first literary works in Dutch.

Periods

700-1100 CE. Old Dutch (Old Low Franconian). Attested by a few texts, mainly fragmentary psalms.

1100-1500 CE. Middle Dutch. Many texts preserved, most of them written in the dialects of Flanders and Brabant. The case system gradually vanished but a three-gender system remained.

1500 CE -present. Modern Dutch. A period characterized by the loss of most of its inflectional morphology and the standardization of the language.

Phonology

Vowels. Dutch has thirteen simple vowels and three diphthongs.

-

a) Monophthongs (13): Dutch has a contrast between short and long vowels which implies a change in quality. Thus, several pairs can be identified: [ɪ] [i:], [ʏ] [y:], [ɛ] [e:], [ɑ] [a:], [ɔ] [o:].

-

Besides, front high vowels show a contrast between roundedness and unroudedness. The low-mid rounded vowel [œ] appears only in diphthongs.

-

b) Diphthongs (3): ɛɪ, œy, ɑu.

Consonants (19):

Script and Orthography

Dutch is written with a Latin-derived alphabet composed of 26 letters:

-

•Pronunciation of vowels varies according to their place in the syllable. When the vowels represented by the letters a, e, i, o, u are the final ones of a syllable (open syllable) they are usually pronounced long: respectively [a:], [e:], [i:], [o:], [y:]. If they are followed by a consonant in the same syllable (closed syllable), they are usually pronounced short: [ɑ], [ɛ/ə], [ɪ], [ɔ], [ʏ]. If, however, there is a long vowel in a closed syllable, it is represented by a digraph:

-

‣[a:] is written aa

-

‣[e:] is written ee

-

‣[i:] is written ie

-

‣[o:] is written oo

-

‣[y:] is written uu

-

•the two remaining long vowels are also represented by digraphs: [ø:] is written eu, [u:] is written oe.

-

•the diphthong [œy] is written ui.

-

•b and d are pronounced [p] and [t] in final position.

-

•[x] is written with g or the digraph ch.

-

•[ŋ] is written with the digraph ng.

-

•q, x and y occurred mostly in borrowed words.

Morphology

-

Nominal

-

•case: most case endings of Dutch have been lost, being in this respect closer to English than to German. They have been preserved to some extent in pronouns and articles.

-

•gender: common gender, neuter. Common gender nouns take the definite article de and neuter nouns take the definite article het.

-

•number: singular, plural. The plural is made by adding en (most frequently) or s to the singular.

-

•articles: Dutch has an indefinite article (een) and definite articles (de/het). The indefinite article is used only with singular nouns. The definite article de is used with singular and plural common gender nouns as well as with plural neuter nouns. Het is used only with singular neuter nouns.

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, reflexive, relative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

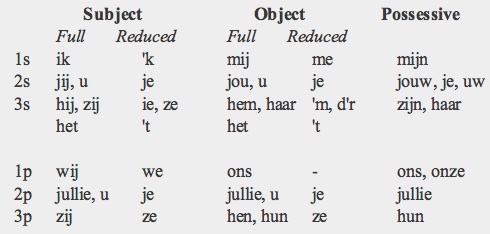

Personal pronouns have subject and object forms, full forms and reduced (non-emphatic) forms. Many non-emphatic pronouns are not usually written.

-

There is also a variety of possessive pronouns.

-

The pronoun u is the polite form for the second person.

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish two deictic degrees (proximal and distal), two genders (common and neuter) and two numbers (singular and plural):

-

The interrogative pronouns are wie (‘who?’), wiens (‘whose?’), wat (‘what?’), and welk(e) (‘which?’). When ‘what?’ combines with a preposition, waar + preposition is used (instead of wat).

-

The relative pronoun is die (common gender) and dat (neuter). With prepositions the form wie is used for persons and waar- for things; wie is placed after the preposition and waar- is prefixed to it e.g. waarop (‘on which’).

-

•compounds: the use of compounds (from Indo-European origin) is preserved in Dutch. These compounds are of the following types: noun-noun, adjective-noun, noun-verb, adjective-verb, particle-verb.

-

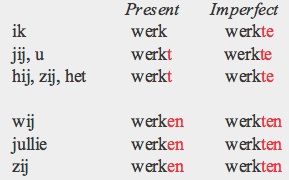

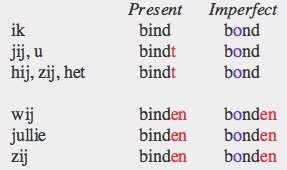

Verbal. In weak (regular) verbs the past tense is formed by adding a dental suffix to the stem. Strong verbs have a vowel change in the past and past participle. The basic distinction in verbal paradigms is between singular and plural. Tense opposition is between past and non-past.

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p. They are conveyed in part by personal pronouns and in part by personal endings.

-

•tense: present and imperfect (simple past) are the only tenses formed without an auxiliary verb. Other, compound, tenses require the auxiliaries hebben (to have), zijn (to be), and zullen (to be/become). They include: perfect, pluperfect, future, future perfect, conditional, conditional perfect.

-

-

As an example we show the conjugation of the weak verb werk (‘to work)’ in the present and imperfect of the indicative:

-

Strong verbs have vowel changes in the stem when forming the imperfect, like in binden (to bind):

-

The perfect tense is formed with the present of the auxiliary verbs hebben or zijn + past participle of the main verb (ik heb gewerkt).

-

The pluperfect is formed with the imperfect of the auxiliary verbs hebben or zijn + past participle of the main verb (ik had gewerkt).

-

The future is formed with the auxiliary zullen + the infinitive (ik zal werken). The future perfect is formed with the present of the auxiliary zullen + past participle + infinitive of hebben/zijn (ik zal gewerkt hebben).

-

The conditional is formed with the past of zullen + the infinitive of the main verb (ik zou werken). The conditional perfect is the past of the future perfect (ik zou gewerkt hebben).

-

•mood: indicative, subjunctive (rare) and imperative. The imperative has only second person, its singular form is the stem (werk) and its plural is identical to the infinitive (werken). Actually, the bare stem can be used for all imperative forms, singular and plural, familiar and polite. The subjunctive is not used anymore, except in some expressions and in older literature.

-

•voice: active, passive.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, present active participle and past passive participle.

-

The infinitive always ends in en. The present participle is formed by adding d(e) to the infinitive. The past participle of weak verbs is formed by adding the prefix ge- to the stem and the suffix -t or -d (gewerkt); if the stem ends in t or d no suffix is added. Verbs beginning with the prefixes be, er, ge, ont, ver, do not add ge. The past participle of strong verbs is formed by prefixing ge- to the stem, which experiences a vowel change, and the suffixing of -en (buigen → gebogen).

Syntax

Grammatical relations are expressed by the use of prepositions. Subjects agree with verbs in person and number. In declarative sentences, subjects precede the verb, in questions they come after the verb. In clauses with a finite auxiliary verb the main verb is placed at the end of the clause. In independent clauses the finite verb is in second position (Subject-Verb-Object); in dependent clauses the finite verb is placed at the end of the clause (Subject-Object-Verb). Except for the positions of the finite and the main verb, other constituents of the clause have considerable word order freedom.

Lexicon

Dutch has borrowed in the past many words from German and French. Some German loans have been adapted to Dutch usage to the point that their origin is indiscernible to most Dutch people. French loans sometimes coexist with Dutch words of the same meaning but the newest word is often preferred. Now, loanwords of all sorts come mostly from English.

Basic Vocabulary

one: een

two: twee

three: drie

four: vier

five: vijf

six: zes

seven: zeven

eight: acht

nine. negen

ten: tien

hundred: honderd

father: vader

mother: moeder

brother: broer

sister: zuster

son: zoon

daughter: dochter

head: kop

face: gezicht

eye: oog

hand: hand

foot: voet

heart: hart

tongue: tong

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Dutch'. J. G. Kooij. In The World's Major Languages, 110-124. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-Dutch Comprehensive Grammar. B. C. Donaldson. Routledge (1997).

-

-Dutch. An Essential Grammar. W. Z. Shetter & I. Van der Cruysse-Van Antwerpen. Routledge 2002.

-

-The Phonology of Dutch. G. Booij. Oxford University Press (1999).

-

-The Morphology of Dutch. G. Booij. Oxford University Press (2002).

-

-A Linguistic History of Holland and Belgium. B. C. Donaldson. Springer (1983).

-

-History of the Dutch Language. Freie Universität Berlin. Available online at:

-

http://neon.niederlandistik.fu-berlin.de/en/nedling/taalgeschiedenis

Dutch

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania