An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Germanic, West Germanic. Other West Germanic languages are English, Dutch, Afrikaans, Frisian and Yiddish.

Overview. With 100 million speakers, German is one of the major European languages and ranks eleventh among the languages of the world. It is the most conservative of the West Germanic languages preserving a substantial inflectional morphology, considerable word order freedom and verb-final sentences. Because of the political fragmentation of Europe during a long period, German has widely varying dialects, with a low degree of mutual intelligibility, and for the same reason the standard form emerged relatively late. Along the last millennium German has developed an outstanding literature.

Distribution. The core of German speakers lives in a continuous area of northern Europe divided now between Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, eastern Belgium, Alsace-Lorraine (France), and South Tyrol (Italy). There are also many German expatriates in other European countries, in North and South America, in Kazakhstan and South Africa.

Speakers. There are more than 90 million speakers of German in Europe and more than 100 million worldwide in the following countries:

Germany

Austria

Switzerland

France

Brazil

USA

Kazakhstan

Russia

Canada

Argentina

Luxembourg

Italy

Hungary

Belgium

Czech Republic

Australia

South Africa

Romania

Chile

Paraguay

Liechtenstein

Denmark

Poland

80,000,000

8,000,000

4,500,000

1,500,000

1,500,000

1,100,000

1,000,000

600,000

550,000

400,000

380,000

270,000

250,000

170,000

100,000

75,000

75,000

50,000

35,000

30,000

30,000

26,000

20,000

Status: German is the official language of Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, and Luxembourg (called Luxembourgish) and one of the official languages of Switzerland and Belgium; it is also official in the Italian region of South Tyrol.

Varieties. There are three main groups of dialects: Low German in the north (comprising North Lower Saxon and Westphalian), Central German (comprising Middle Franconian, Rhine Franconian and Thuringian), and Upper German in the south (comprising Swabian and Alemannic). The Central and Upper dialects together constitute High German which is the standard language.

Low German was not affected by the consonant changes developed in High German known collectively as the Second Sound Shift (The First Sound Shift is common to all Germanic languages). Because of this change, inherited voiceless stops became affricates or fricatives (depending on whether they were word-initial or not), and voiced stops were devoiced.

Oldest Documents.

c. 800 CE. The Merseburger Zaubersprüche (Merseburg charms), two magic pagan spells discovered in the Merseburg library written in Old High German.

c. 800 CE. Hildebrandslied (Hildebrand's Song), a fragment of a heroic song depicting a tragic encounter in battle between a son and his unrecognized father.

Periods (High German)

Old High German (700-1050). Comparatively few texts, most of them religious in nature.

Middle High German (1o50-1350). Development of secular literature.

Early New High German (1350-1650). With the invention of the printing press began a slow process of standardization. It became the preferred medium for writing in the north, supplanting Low German for that purpose.

New High German (1650-present). It gradually became the standard written and spoken language.

Phonology

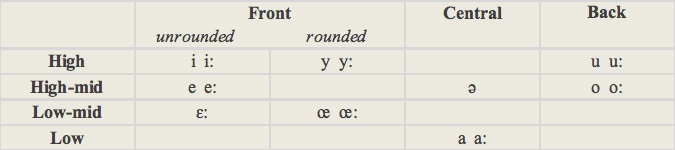

Vowels. German's vowel system is characterized by the contrast between short and long vowels as well as between front rounded and front unrounded vowels. Short vowels are pronounced in a lax way while long vowels are tense.

-

a) Monophthongs (16):

-

b) Diphthongs (3): ai, oi, au.

Consonants (21). Voiced stops and fricatives in word-final position become voiceless. Voiced [b] before consonants [t] and [s] changes to [p]. The velar and palatal fricatives have an almost complementary distribution. The velar fricative [x] occurs after central and back vowels, never in initial position; while the palatal one [ç] occurs after front vowels, the consonants n, l, r, and in word initial position. [r] has several allophones including a uvular trill or fricative [ʀ] when it is followed by a vowel.

There are several possible affricates in German, like [pf] and [ts], but their status is debated; many linguists think that their nature is bisegmental (two successive sounds instead of a single one).

Script and Orthography

German is written with a Latin-derived alphabet containing 26 letters (equivalents in the International Phonetic Alphabet are shown between brackets):

*nouns are written with an initial capital letter.

*front rounded vowels are represented with umlauts:

-

[y] by ü (Mütter); [y:] by ü (Güte) or üh (führe)

-

[œ] by ö (Hölle); [œ:] by ö (höre) or oe (Goethe)

*the remaining long vowels are represented:

-

[i:] by ie (bieten) or ih (ihre)

-

[u:] by u (Rute) or uh (Ruhm)

-

[e:] by e (beten) or eh (zehre)

-

[o:] by o (rote) or oh (Sohn)

-

[ɛ:] by ä (bäte)

-

[a:] by a (rate), ah (Bahn) or aa (Haare)

*the mute vowel [ə] is represented by e (bitte)

*the diphthongs are represented:

-

[ai] by ei (Bein)

-

[oi] by eu (Leute)

-

[au] by au (Laute)

-

•[ç] and [x] are represented both by the digraph ch (mich and loch, respectively).

-

•[ŋ] is represented by the digraph ng (rang).

-

•[ʃ] is represented by s (Stein) or the trigraph sch (Schatz).

-

•the symbol ß is often used instead of ss.

Morphology. In contrast with many modern Germanic languages, German has retained an extensive inflectional morphology.

-

Nominal. Nominal phrases are inflected for gender, number and case.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine, neuter. Noun gender can only be identified through agreement as the noun itself does not have any obvious phonological or semantic distinctive features.

-

•number: singular, plural. Plurals are marked by suffixing, by stem vowel mutation or by both.

-

Plurals end in: -e (Tag/Tage), -(e)n (Blume/Blumen, Frau/Frauen), -s (Anger/Angers) or are indicated by stem vowel mutation plus -e (Nacht/Nächte), stem vowel mutation plus -er (Mann/Männer, Buch/Bücher) or stem vowel mutation alone (Apfel/Äpfel).

-

Some nouns have identical singular and plural forms (Fenster/Fenster).

-

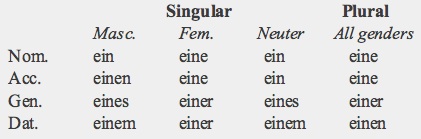

•articles: German has an indefinite and a definite article which are fully declined in four cases (see below).

-

•case: nominative, accusative, genitive, dative.

-

The marking for case is carried mainly by the adjective, the definite article and other determiners but not, generally, by the noun itself. Declensional types are not based on the stem's phonology but on the noun's gender. For example, the declension of masculine noun Mantel (cloak), feminine Nase (nose), and neuter Buch (book), accompanied with that of their definite articles, is:

-

In the plural, nominative, accusative and genitive are identical while the dative adds -(e)n,

-

or zero if the nominative plural already ends in n.

-

The indefinite article declines in a similar way to that of the definite one:

-

•adjectives: Adjectives have two types of declension: weak and strong. The weak declension occurs when an adjective is accompanied by the definite article or by a demonstrative or by some other determiner like welcher (‘which’), jeder (‘each’), alle (‘all’). The strong declension of adjectives occur when they are not preceded by any of the above; they carry more grammatical information as this is not provided by determiners. The strong and weak declensions of gute (‘good’) are:

-

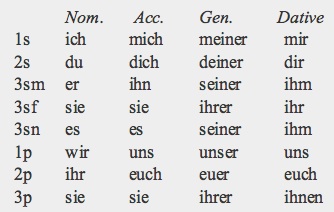

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

Personal pronouns: are inflected for case and number as well as for gender in the 3rd person singular :

-

-

The 2nd person has a polite form that is formally identical to the 3rd plural but written with an initial capital letter (Sie, Sie, Ihrer, Ihnen).

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish two deictic degrees: ‘this’ (masc. sg. dieser, fem. sg. diese, neuter sg. dieses, plural diese) and ‘that’ (masc. sg. jener, fem. sg. jene, neuter sg. jenes, plural jene).

-

The interrogative pronouns are wer (‘who?’) and was (‘what?’).

-

The main relative pronoun is: singular der/die/das, plural die (‘who, which, that’). It agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent. When the antecedent is an unspecified person, wer (‘who’) is used. When the antecedent is an indefinite neuter noun, adjective or pronoun or an entire main clause was (‘which’) is employed. A less frequent relative pronoun is welcher (fem. welche, neuter welches, plural welche) used primarily to avoid repetition.

-

•compounds: the most frequent type is that formed by two (or more) nouns, the first functioning like an adjective: Hundehütte (Hunde=dog + Hütte=hut).

-

Verbal

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p.

-

•mood: indicative, subjunctive, imperative, conditional.

-

•tense: present, past, perfect, pluperfect, future, future perfect.

-

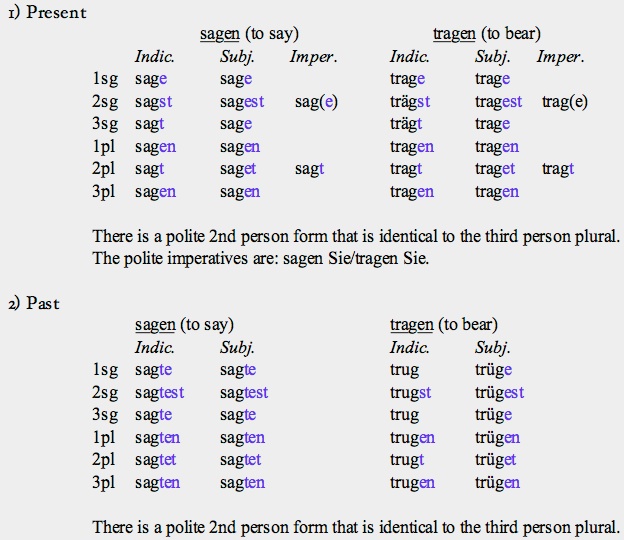

The present and past are the only tenses formed without an auxiliary verb. The conjugations of the weak verb sagen and the strong verb tragen are:

-

Compound tenses are formed with inflected auxiliaries plus a non-finite form (infinitive or past participle). The auxiliaries are haben (to have), sein (to be) and werden (to be/become). The compound tenses are: perfect, pluperfect, future, future perfect.

-

Perfect: present of haben + past participle e.g. Ich habe getragen (I have carried)

-

Pluperfect: past of haben + past participle e.g. Ich hatte getragen (I had carried)

-

Future: present of werden + infinitive e.g. Ich werde tragen (I will carry)

-

Future perfect: future of haben + past participle e.g. Ich werde getragen haben (I will have carried)

-

Conditional: past of werden + infinitive e.g. Ich würde tragen (I would carry)

-

Conditional perfect: conditional of haben + past participle e.g. Ich würde getragen haben (I would

-

have carried)

-

•voice: active, passive.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, present active participle, past passive participle.

-

The past participle is formed by the addition to the stem of the prefix ge- and of a suffix which is -t in weak verbs and -en in strong verbs. If the first syllable of the verb is not stressed ge- is not added. For example:

-

infinitive: sagen; tragen

-

present participle: sagend; tragend

-

past participle: gesagt; getragen

Syntax

The underlying word order is Subject-Object-Verb. However, the position of the verb varies. It is final in subordinate clauses but first or second in main clauses (respectively, in questions and statements). Non-finite verbs are always final even in main clauses. The positioning of other sentence-level constituents is relatively free.

1) Main clauses

-

a) finite (statement): 2nd position

-

Heinricht liebt die Frau.

-

Heinrich loves the woman

-

Heinrich loves the woman.

-

b) finite (question): 1st position

-

Liebt Heinricht die Frau?

-

loves Heinrich the woman

-

Does Heinrich love the woman?

-

c) finite + non-finite (infinitive): 2nd position + final position

-

-

Sie möchte noch einmal tanzen.

-

she liked once more to dance

-

She liked to dance once more.

-

d) finite + non-finite (past participle): 2nd position + final position

-

Mein Bruder ist nach Paris gefahren.

-

my brother has to Paris travelled

-

My brother has travelled to Paris.

2) Subordinate clauses

-

a) finite: final position

-

Ich weiss, das Heinrich die Frau liebt.

-

I know that Heinrich the woman loves

-

I know that Heinrich loves the woman.

-

b) finite + non-finite (past participle): final position (non-finite preceding finite)

-

Ich glaube, das mein Vater vor einigen Tagen nach London gefahren ist.

-

I believe that my father ago several days to London travelled has

-

I believe that my father has travelled to London several days ago.

Basic Vocabulary

one: ein/eins

two: zwei

three: drei

four: vier

five: fünf

six: sechs

seven: sieben

eight: acht

nine: neun

ten: zehn

hundred: hundert

father: Vater

mother: Mutter

brother: Bruder

sister: Schwester

son: Sohn

daughter: Tochter

head: Kopf

face: Gesicht

eye: Auge

hand: Hand

foot: Fuss

heart: Herz

tongue: Zunge

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'German'. J. A. Hawkins. In The World's Major Languages, 86-109. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-Complete German Course for First Examinations. L. J. Russon. Longman (1967).

-

-Hammer's German Grammar and Usage. M. Durrell. Hodder Education Publishers (2011).

-

-Geschichte der deutschen Sprache. A. Bach. Quelle and Meywe (1965).

German

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania