An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Italic, Romance.

Overview. After the fall of the Roman Empire, spoken Latin gave birth to many regional Romance languages in the Italic peninsula. During the Renaissance, an archaic form of Tuscan was chosen as the standard but remained more a literary language than an oral one. Only after the unification of Italy in 1861, Tuscan spread (rather slowly) to all regions and social classes, though the old regional languages, considered now as dialects of Italian, remained strong. Due to its prolonged literary character, Italian changed very little across the centuries, being one of the most conservative Romance languages.

Distribution. The vast majority of Italian speakers live in the Italic peninsula, namely in Italy but also in San Marino and in the Vatican. Italian is also spoken in parts of France (Alps, Côte d'Azur, Corsica), Switzerland and Malta, as well as in small communities in Croatia and Slovenia. Several waves of migrants carried the language outside Europe, mainly to North America (Canada, USA) and South America (Argentina, Brazil) but also to Australia and Africa (Ethiopia, Somalia and Libya).

Speakers. More than 63 million people speak Italian as a first language:

Italy

Argentina

France

USA

Switzerland

Canada

Brazil

Australia

Malta

59,000,000

1,000,000

1,000,000

700,000

470,000

450,000

400,000

270,000

120,000

Status. Italian is the official language of Italy, San Marino, and (together with Latin) of the Vatican City. Italian is also the official language of Switzerland's Ticino canton and is widely spoken in the island of Malta.

Varieties. Italian has many dialects that can be grouped geographically into northern, central and southern:

-

Northern dialects divided into Gallo-Italian (Piedmontese, Ligurian, Lombard, Emilian-Romagnol), and Venetan (Venetian, Veronese, Trevisan, Paduan).

-

Central dialects: Tuscan; dialects of the Marche (Marchigiano), Umbria, and northern Lazio.

-

Southern dialects: Abruzzian, Neapolitan, Pugliese, Calabrian and Sicilian.

Northern dialects are separated from the others by the so-called La Spezia-Rimini line which also separates Western Romance languages (French, Spanish, Portuguese) from Eastern Romance ones (Italian, Romanian). Thus, they are closer to French than to Central and Southern dialects in some aspects of their phonology and grammar.

Oldest Documents

960 CE. The Placito Capuano is the first in a number of acts (Placiti Cassinesi), recording a court case related to the ownership of land.

late 11th c. Inscription in the church of San Clemente, in Rome, in the form of a dialogue between a pagan and a Christian saint.

late 11th c. Confessione di Norcia, written in a manuscript found in the abbey of San Eutizio, is a formula for the Christian rite of confession.

end of 12th c. Ritmo Laurenziano (‘Laurentian Rhythm’), the first poem in Italian, soon followed by many others.

Phonology

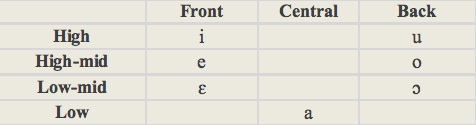

Vowels (7). Italian has a seven-member, symmetrical, vowel system. Most Italian words end in a vowel.

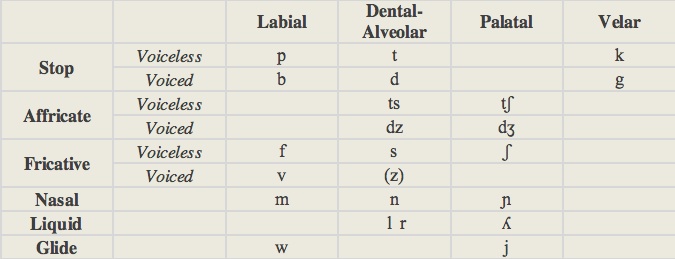

Consonants (23): There are two series of stops and affricates, voiceless and voiced, articulated at four points. Most Italian speakers do not contrast [s] and [z]. When s in initial position is followed by a vowel it is pronounced [s]. Between vowels, northern speakers pronounce it [z] and southern speakers [s] with a few exceptions.

Script and Orthography

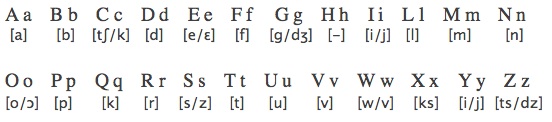

Italian is written with a Latin-based alphabet of 23 letters (equivalents in the International Phonetic Alphabet are shown between brackets):

-

•[e] and [ɛ] are not distinguished orthographically though in stressed final position they are indicated with different accents: [e] as é, [ɛ] as è.

-

•[o] and [ɔ] are not distinguished orthographically.

-

•c is pronounced [k] before a, o, u, but as [tʃ] before i, e.

-

•The digraph ch is pronounced as [k] before i, e, while the digraph ci is pronounced [tʃ] before a, o, u.

-

•g is pronounced [g] before a, o, u, but as [dʒ] before i, e.

-

•The digraph gh is pronounced as [g] before i, e, while the digraph gi is pronounced [dʒ] before a, o, u.

-

•s is pronounced [z] in intervocalic position in some dialects.

-

•[ʃ] is written with the digraph sc before i, e.

-

•[ɲ] is written with the digraph gn.

-

•[ʎ] is written with the digraph gl.

Morphology

-

Nominal

-

•case: the case system of Latin has completely collapsed, except for some remaining cases in the personal pronouns.

-

•gender: masculine and feminine. Most nouns ending in o are masculine, those ending in a are mostly feminine (with the exception of Greek loanwords that are generally feminine), those ending in e or i can be either masculine or feminine.

-

•number: singular and plural. In contrast to Western Romance languages such as French, Spanish and Portuguese, the plural is made by vowel alternation instead of adding the suffix s: olivo (m.s, ‘olive tree’) → olivi (m.p) , oliva (f.s, ‘olive fruit’) → olive (f.p). Nouns (masculine or feminine) ending in e make their plurals in i e.g. padre (‘father’) → padri, madre (‘mother’) → madri. Nouns ending in i, stressed vowels or consonants are unchanged in the plural e.g. crisi (‘crisis, crises’), città (‘city, cities’), sport (‘sport, sports’). Some plurals are irregular e.g. uomo (‘man’) → uomini (‘men’), dio (‘god’) → dei (‘gods’).

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite, relative.

-

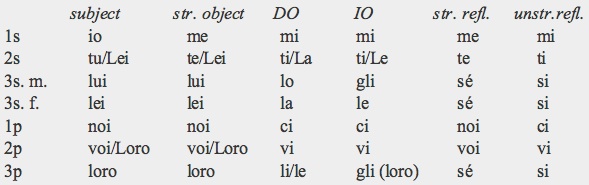

Personal pronouns are genderless except for the 3rd person singular. There are several types: subject, stressed object (direct and indirect), unstressed direct object, unstressed indirect object, stressed reflexive and unstressed reflexive.

-

Subject pronouns are not essential because the verb has all necessary information about person and number; they are stressed and used for emphasis (Lei and Loro are formal). The stressed object pronouns are formally identical to the subject ones except in 1st and 2nd singular; they are also emphatic and may be used as direct or indirect object (the latter with a preposition). The unstressed object pronouns are preferred in most situations and are always used without a preposition; they are placed before the verb (e. g. me lo darà [‘he will give it to me’]) except after an imperative or a non-finite verb (infinitive, gerund, participle) when they are attached to the end of the verb (e. g. deve darmelo [‘he must give it to me’]). Reflexive pronouns have also stressed emphatic forms and unstressed unemphatic ones.

-

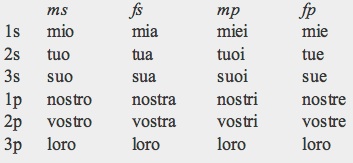

Possessive pronouns are always preceded by an article and distinguish gender and number:

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish near and remote locations as well as gender and number:

-

-

Italian has two invariable interrogative pronouns: chi (‘who?, whom?’), che (‘what?’). Besides, it has interrogative adjectives that can also be used as pronouns: quanto (‘how much?’) inflected for gender and number, and quale (‘which?’) inflected only for number.

-

There are several indefinite pronouns like: uno/a (‘one, somebody’), qualcuno/a ('someone, somebody’), qualcosa (‘something’), ognuno (‘each one’), chiunque (‘anyone’). Negative indefinites are niente and nulla, both meaning ‘nothing’.

-

Among the relative pronouns, the invariable che (‘who, whom, that’) is the most frequently employed; it can function as subject and direct object. Cui (‘which, to whom, whose’) and chi (‘who’) are also invariable and commonplace. The first one is preceded by a preposition and is used for the indirect object and complements, the second one refers to persons only and is always used with a singular verb. Another relative pronoun indicates person and number and is used in conjunction with the definite article: il quale (ms), la quale (fs), i quali (ms), le quali (mp).

-

•articles: Italian has indefinite and definite articles which distinguish gender and number. Indefinite: un/uno (m.s.), un'/una (f.s.); it has no plural. Definite: il/lo/l' (m.s.), la/l' (f.s.), i/gli (m.p.), le (f.p.).

-

Verbal

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p

-

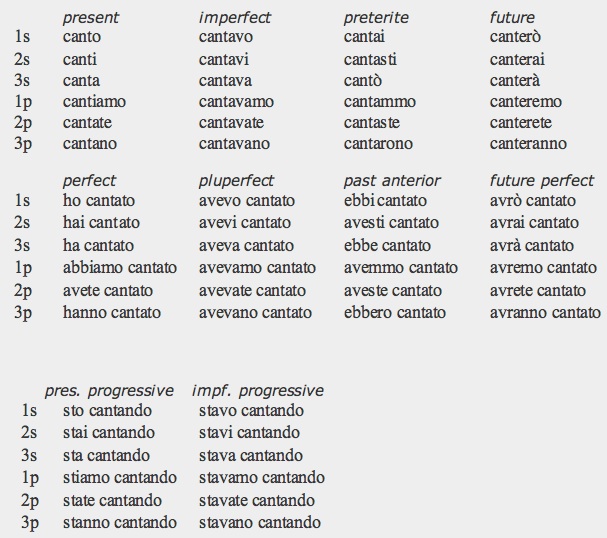

•tense: present, imperfect, preterite and future are the basic tenses.

-

The compound ones include perfect and progressive forms derived from the simple tenses. The perfect tenses are: perfect, pluperfect, past anterior, future perfect. The progressive tenses are: present progressive, imperfect progressive. The perfect tenses of transitive verbs are formed with the auxiliary avere (‘to have’) + past participle, and the progressive tenses with the auxiliary stare (‘to be’) + gerund. Intransitive verbs normally use essere as an auxiliary except for camminare, dormire, giocare, passeggiare, piangere, riposare, viaggiare. The conjugation of the verb cantare (‘sing’) in the indicative mood is:

-

The perfect uses the present of avere, the pluperfect its imperfect, the past anterior its preterite, the future perfect its future.

-

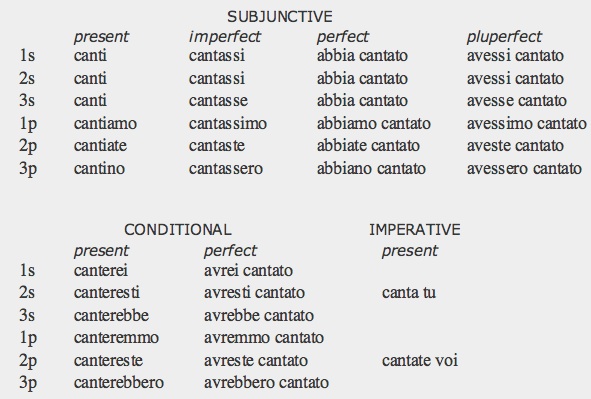

•mood: indicative (all tenses), subjunctive (present, imperfect, perfect, pluperfect), conditional (present, perfect), imperative (present).

-

The present and imperfect subjunctive are simple tenses, the perfect and pluperfect require an auxiliary. The subjunctive perfect is formed with the present subjunctive of the auxiliary avere + the past participle of the lexical verb, the subjunctive pluperfect with the imperfect of the same auxiliary + the past participle. The conditional perfect is formed with the present conditional of avere + the past participle.

-

•voice: active, passive.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive (present and past), gerund (present and past), present participle, past participle.

-

present infinitive: cantare

-

past infinitive: avere cantato

-

present gerund: cantando

-

past gerund: avendo cantato

-

present participle: cantante

-

past participle: cantato

-

The infinitive is used with modal verbs without a preposition or to express purpose, cause or consequence accompanied with the preposition per (‘for’). The gerund is always dependent on another verb and it expresses an action simultaneous to that of the main verb; the compound gerund indicates that an action happened before that of the main verb. The past participle has a passive sense and it behaves both as adjective and verb.

Syntax

The neutral word order in sentences with transitive verbs, as well as with some intransitive ones, is Subject-Verb-Object, but it can be reversed to give emphasis to the object. With intransitive verbs, that take essere as an auxiliary the order may be predicate-subject (e.g. è arrivato il treno).

The noun is usually accompanied by determiners (articles, demonstratives, possessives, quantifiers) and, sometimes, by adjectives. Determiners precede the noun, and possessives must be preceded by an article or a demonstrative, except in the case of kinship terms. Adjectives may come before or after the noun depending on its function; if it is descriptive or emphatic the adjective precedes the noun, if it is used to distinguish the noun from another one the adjective follows it. Syntactic relations are indicated mainly by prepositions.

For example, in the following sentence (modified from Gli occhiali d'oro by the writer G. Bassani):

Una bella mattina, (mentre passavo sotto il portico del caffè della Borsa), in corso Roma, un uomo

a beautiful morning (while passing under the porch of the café of the Borsa), in street Roma, a man

vecchio gridò improvvisamente il mio nome.

-

old shouted suddenly the my name.

-

brown: subject, red: direct object, underlined: verbs

A beautiful morning, while I was passing under the porch of Borsa’s café, in Roma street, an old man shouted suddenly my name.

This is a complex sentence with a main clause and a temporal subordinate clause (enclosed between brackets) introduced by mentre. Subordinate clauses frequently follow the main one, but they can also precede it (as in the example). The order of the main clause is: Complements-Subject-Verb-Object.

Articles, indefinite (un) and definite (l', la, il), as well as the possessive pronoun (mio), being all determiners, precede their nouns. The adjective vecchio, that serves to distinguish one man from another (e.g. a younger one) follows the noun; in contrast, bella is a descriptive adjective and, thus, precedes the noun. Prepositions (sotto, in) help to clarify syntactical functions.

Yes-no questions have the same form as statements but are differentiated by raising the pitch of the voice. Information-seeking questions are posed by placing an interrogative pronoun or adjective at the beginning of a phrase. Negative statements or questions are formed by placing non immediately before the verb. When answering negatively to a question no is used.

Basic Vocabulary

one: uno

two: due

three: tre

four: quatro

five: cinque

six: sei

seven: sette

eight: otto

nine: nove

ten: dieci

hundred: cento

father: padre

mother: madre

brother: fratello

sister: sorella

son: figlio

daughter: figlia

head: testa

face: faccia

hand: mano

eye: occhio

foot: piede

heart: cuore

tongue: lingua

Key Literary Works

1275-1300 Poems. Guido Cavalcanti

-

Guido was a Florentine poet who left about 50 poems in the dolce stil nuovo ("sweet new style"), influenced by Provençal poetry, which had as main subject love for an idealized woman. They include, sonnets, ballads, and two canzoni, one of which, Donna mi prega ["A Lady Asks Me"], is a deep analysis of love.

-

1308-21 Divina Commedia (Divine Comedy). Dante Alighieri

-

A long narrative poem, a journey undertook by the poet through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Guided by the poet Virgil in the beginning, he is then led through Paradise, to his salvation, by his beloved Beatrice, and at the end of his journey, from darkness to light, he has a vision of God.

-

1330-74 Canzoniere (Song Book). Francesco Petrarca

-

The Canzoniere is made up by 366 poems of which most are sonnets, the vast majority of them addressed to his beloved Laura. In them he explores his thoughts and emotions arising from by his deep love for her, expressing at times uncertainty and anguish. In the end he achieves a more peaceful state by superseding human love by the spiritual incarnated in the Virgin.

-

1348–53 Decameron (Ten Days' Work). Giovanni Boccaccio

-

A collection of 100 stories recounted by ten narrators in ten days, seven women and three men, who, to escape the Black Death striking Florence in 1348, retreat to the nearby hills. Their tone alternates between the gloomy, the comic, and the licentious constituting a Human Comedy where men and women are masters of their own destiny instead of depending on the divine. Subject and style (a masterful prose) are harbingers of the Renaissance.

-

1513 Il Principe (The Prince). Niccolò Machiavelli

-

Basing his short and readable work on earlier books of advice to rulers, Machiavelli makes, however, a radical break with tradition recommending that the prince should behave not according to some moral ideal but in the best way to acquire and preserve power, make war and obtain glory.

-

1513-18 Il libro del Cortegiano (The Book of the Courtier). Baldesar Castiglione

-

Purporting to recount conversations taken place at the court of Urbino, during four days, about the ideal qualities and behavior of a courtier, it was in fact composed and rewritten over several years. The participants, men and women, discuss lively about their subject giving, often, opposing views and, as several of them were dead when the book was written, they represent a nostalgic evocation of a small but cultured Italian court.

-

1516-32 Orlando furioso (Mad Orlando). Ludovico Ariosto

-

A narrative poem that reached 46 cantos in the 3rd and final edition, a continuation and reshaping of Boiardo's Orlando Innamorato. It is a collection of episodes derived from the romances and heroic poetry of the Middle Ages which follow three main strands: the wars between Charlemagne and the Saracens, the unrequited love of Orlando for Angelica that makes him mad and the troubles of the Saracen warrior Ruggiero in his path to become a Christian ruler.

-

1575 Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Liberated). Torquato Tasso

-

A historical epic poem about the capture of Jerusalem during the First Crusade, intertwined with invented romantic episodes, in which the author expresses his sensual and lyrical vein.

-

1764 Plays. Carlo Goldoni

-

In his numerous plays the Venetian playwright changed radically the Italian comedy by getting rid of the customary masks and by creating more realistic characters, based often on the bourgeois world, who speak in everyday language (frequently in Venetian dialect). The absurd and repetitive plots of the traditional commedia dell'arte are replaced by new and ingenious ones.

-

1820 Dei sepolcri (Of the Sepulchres). Ugo Foscolo

-

A patriotic poem, in blank verse, that stimulated the national revival of the Risorgimento, composed as a response to Napoleon's edict forbidding burials outside cemeteries and tomb inscriptions for heroes and virtuous men of the past. The central theme of Foscolo's cogitations, which don't follow a logical order, is that the dead exist only in the memory of the living, and the recollection of their thoughts and actions may be a source of inspiration to them.

-

1877-93 Odi barbare (The Barbarian Odes). Giosuè Carducci

-

Carducci try to transpose classical meters in modern Italian verse which might have sound strange ("barbarian") to the ancients. Some of his most memorable lyrics contrast, like in "Before the Baths of Caracalla" and "The Square of San Petronio", the grandeur of the irrecoverable past with the disenchantment of the present. In "At the Station on an Autumn Morning" the urban landscape underlines his feelings of loss at the parting of his beloved; in "Snowfall" a winter storm portends death.

-

1881 I malavoglia (The Malavoglia Family). Giovanni Verga

-

Translated in English as "The House by the Medlar Tree", this novel tells the tragic story of the Sicilian Toscano family struggling to survive as fishermen amid the pressures generated by the unification of Italy and the expansion of capitalist enterprise. It ends with the dissolution of the family.

-

1904 Il fu Mattia Pascal (The Late Mattia Pascal). Luigi Pirandello

-

A philosophical novel inquiring about the nature of a person's identity. By a stroke of luck Mattia Pascal is presumed dead and has the opportunity to abandon his dreadful life and start a different one. But without his past he feels empty, without being reflected in the persons he knew he seems to lack a persona. So he tries to go back to his previous life but people have adjusted to his "death" and nobody recognizes him anymore.

-

1921 Sei personaggi in cerca d'autore (Six Characters in Search of an Author). Luigi Pirandello

-

A ground-breaking play in which six imaginary characters rejected by their creator search for an author to give them direction and meaning, but not finding one must act in the stage and in the process define who they are. They, like us, have no ultimate essence, they are what they do.

-

1923 Coscienza di Zeno (Confessions of Zeno). Italo Svevo

-

A first-person narrative composed by the memoirs written down in his old age by the businessman Zeno Cosini as a prelude to his psychotherapy. In them, Zeno discloses his inner thoughts and feelings, his ways of deception, his contradictions…and the conclusion that life is an illness without cure.

-

1940 Il deserto dei Tartari (The Tartar Steppe). Dino Buzzati

-

Narrates with irony the story of an army lieutenant posted to a frontier military post at the edge of a desert, waiting for years an enemy who never comes. His friends in the city live fruitful lives while his is suspended in expectation. When the Tartars finally arrive he fells ill and is dismissed.

-

1947 Cronache di poveri amanti (A Tale of Poor Lovers). Vasco Pratolino

-

A depiction of working-class people social and political relations in Florence during the 1920s at the beginning of Fascism.

-

1947 Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man). Primo Levi

-

An autobiographic work recounting his own experiences at the Nazi concentration camp of Auschwitz, and a profound, insightful, meditation about the human condition when man is trapped in a atrocious situation.

-

1958 Il gattopardo (The Leopard). Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

-

His only completed novel, rejected by the editors and published posthumously, opens in 1860 when Garibaldi lands in Sicily and the unification of Italy is about to take place. The main protagonist, the aristocratic prince Don Fabrizio, is a conservative who regards with detachment an emerging new social order, thinking that everything has to be changed in order to change nothing. In contrast, the ascending liberal bourgeoisie accommodates to the new political circumstances seeking personal profit.

-

1959 Una vita violenta (A Violent Life). Pier Paolo Pasolini

-

The novel traces the political and moral evolution of Tommasino Puzzilli belonging to the subproletariat of a Rome impoverished by World War II. In the spirit of Neorealism, the characters speak in the Roman dialect employed by the low classes in the 1950s, and social conditions and violence are depicted with sordid authenticity.

-

1962 Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini (The Garden of the Finzi-Contini). Giorgio Bassani

-

This nostalgic, partially autobiographical, work evokes the life of the Jewish community of Ferrara during the years before WW II when discriminatory racial laws progressively restrict their world and change their social relations. As a consequence, the author who belonged to a middle-class family is able to interact with the aristocratic Finzi Continis who up to then had been inaccessible to him. He is attracted to Micòl, their enigmatic and unpredictable daughter, though she offers him only friendship. In the end we learn that the entire Finzi Contini family was annihilated by the Nazis.

-

1974 Morte accidentale di un anarchico (Accidental Death of an Anarchist). Dario Fo

-

A farcical play based on a true event: the "accidental" death of an anarchist worker fallen from a window of a Milan police station. An investigation, conducted by a madman, posing as a judge, reveals the contradictions of the police account.

-

1980 Il nome della rosa (The Name of the Rose). Umberto Eco

-

At the same time, a detective story set in medieval Italy, a reflexion about the interpretation of signs and symbols (reflecting his studies in semiotics) and a philosophical investigation about truth and the existence of order in the Universe.

-

1994 Sostiene Pereira (Pereira Maintains). Antonio Tabucchi

-

A less than famous journalist, an apolitical lover of literature and good food, is confronted to a moral dilemma in 1938 Portugal, under the oppressive Salazar's dictatorship, when a leftist young collaborator is killed by the police.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Italian'. N. Vincent. In The World's Major Languages, 233-252. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-Modern Italian Grammar. A. Proudfoot & F. Cardo. Routledge (2005).

-

-The Italian Language Today. A. L. Lepschy & G. C. Lepschy. Hutchinson (1977).

-

-The Italian Language. B. Migliorini & T. G. Griffith. Faber and Faber (1984).

Italian

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania