An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Italic. Latin shares several features with Faliscan spoken to the north of Latium, and is generally agreed that both languages form a sub-group. Some scholars think that Latin and Sabellian languages have enough similarities to be grouped with Faliscan into the Italic branch.

Overview. Latin was the language of small Indo-European populations living in Latium, a region of the central Italic Peninsula, which by an accident of history became the founders of the largest empire the Ancient World ever saw. The spread of their tongue accompanied their territorial expansion.

With the fall of the Roman Empire, Latin ceased, eventually, to be spoken but was the seed of the Romance languages, of which Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French and Romanian came to be the national languages of five central and south European countries. Throughout the Middle Ages, and until recently, Latin remained the language of literature and scholarship in the West, as well as the liturgical language of the Roman Catholic Church.

Distribution. Originally spoken along the lower Tiber River, in the region of Latium, Latin spread throughout Italy and most of western and southern Europe as well as into the central and western Mediterranean coastal regions of Africa.

Status. Extinct. Latin is documented from the 7th century BCE onwards. Even if it is no longer spoken, the prestige of the language assured the survival of written Latin until today. It is one of the official languages of the Vatican.

Varieties. All forms of Latin that depart from the classical norm are known as Vulgar Latin, a term specially applied to informal and/or spoken Latin.

Periods

Early Latin (600-200 BCE). Known mainly by inscriptions.

Classical Latin (200 BCE-200 CE). Attested by abundant literature and a wealth of inscriptions.

Post-Classical Latin (200-400 CE). The more artificial literary language of post-classical authors.

Late Latin (400-600 CE). It was the administrative and literary language of Late Antiquity in the Roman Empire and its successor states in Western Europe.

Medieval Latin (600-1300 CE). Latin ceased to be a spoken language but it was employed for literature, science and administration as well as by the Roman Catholic Church for its liturgy.

Renaissance Latin and Neo-Latin (1300 till now). During the Renaissance, the Humanist movement purged Medieval Latin of some phonological, orthographical and lexical changes. A similar version of this reformulated language continued to be used after the Renaissance for scientific and literary purposes (usually called Neo-Latin).

Oldest Documents

7th c. BCE. The Praeneste fibula, a golden cloak pin carrying a four-word inscription. Its authenticity has been doubted.

7th c. BCE. The Duenos inscription, engraved in a triad of small vessels, found in the Quirinal Hill in Rome. Its translation and interpretation are uncertain.

570-550 BCE. A fragmentary inscription on a stone block found in a shrine (Lapis Niger) of the Roman Forum. It seems to be some kind of ritual admonition.

Phonology

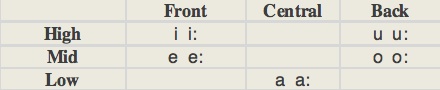

Vowels (10). Latin had five short and five long vowels. Vowel length was phonemic.

In Classical Latin there were nasalized vowels but only at the end of a word or before a sequence of nasal + continuant (fricative or liquid).

Latin had a number of diphthongs. In Early Latin: ei, ai, oi, au, ou, eu. In Classical Latin: au, ae (from ai), oe (from oi) and eu; the remaining diphthongs of Early Latin were monophthongized.

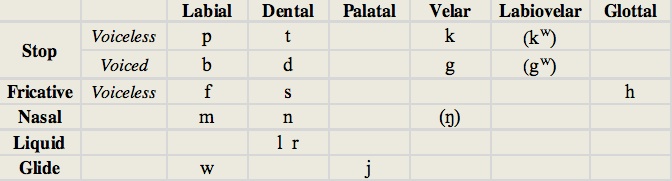

Consonants. Latin stops were articulated at four different places (labial, dental, velar and labiovelar), having contrasting voiceless and voiced sounds. The phonological status of labiovelars is debatable as well as that of the nasal velar. Latin had two other nasals and three voiceless fricatives, besides four liquids and glides.

Stress. In Early Latin, stress fell on the first syllable of every word. In Classical and Post-Classical Latin, stress fell on the penultimate syllable if it was long, but if it was short on the antepenultimate.

Script and Orthography

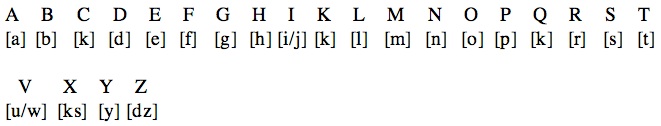

The Latin alphabet derives from a variety of the Greek alphabet introduced into Italy by Euboean colonists. The Classical Latin alphabet had 23 letters (there were no "lower case" letters):

-

•vowel length was not distinguished in writing, thus a may represent [a] or [a:], i can be [i] or [i:], etc.

-

•Y and Z were used to write Greek loanwords.

-

•C and K both represented the sound [k], but the latter was rarely used in the Classical Age.

-

•X represented the consonant group [ks].

-

•the labiovelars [kʷ] and [gʷ] were written with the digraphs QU and GU.

-

•the nasal velar [ŋ] was represented by N before velars and G before nasal consonants.

-

•in the Middle Ages a few more letters were added to the Latin alphabet in order to get rid of ambiguities: as I was used for both [i] and [j] sounds, J was introduced to represent [j]; as V was used for [w] and [u], U was introduced to represent [u]. Another later addition was W, originally a duplication of V.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Nouns are inflected for gender, number and case.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine, neuter.

-

•number: singular, plural.

-

•case: nominative, vocative, accusative, genitive, dative, ablative.

-

Th ablative also served as the instrumental and, in part, as the locative. The locative is replaced for most nouns by a combination of preposition and ablative, but the locative is retained for some geographical proper names and a few nouns denoting place.

-

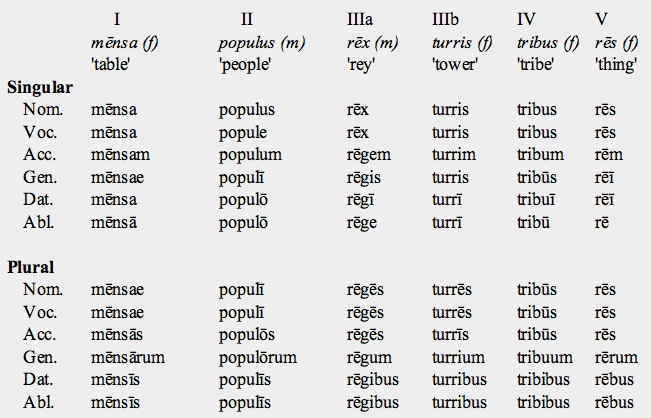

Latin has five declension types, one of which has two subtypes. They are a continuation of Proto-Indo-European types except type V which is an innovation. Most nouns in declensions I and V are feminine while most in declensions II and IV are masculine. Class III is the largest and includes nouns of all three genders. Neuter nouns, which occur in types II, III and IV, have specific forms only in the nominative-vocative-accusative: e.g. class II iugum (‘yoke’) has the single form iugum for nominative, vocative and accusative)

-

•pronouns: personal, reflexive, demonstrative, relative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

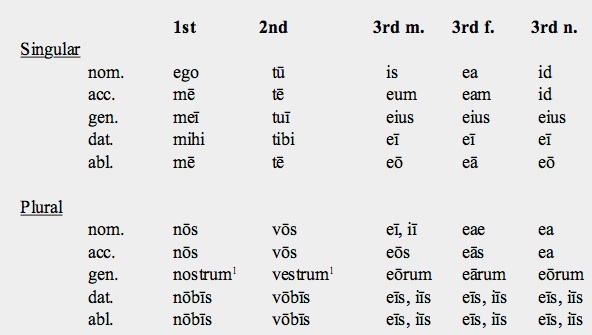

Latin pronouns are inflected, like nouns, for number, gender and case. However, personal pronouns are genderless and have forms only for the first and second persons; for the third person, anaphoric and reflexive pronouns are used. Personal pronouns in the nominative are usually omitted because the verb carries all the necessary information about person and number.

-

1. nostrī and vestrī are alternative forms.

-

The reflexive pronoun has only oblique forms which don't distinguish gender and number: accusative and ablative sē, genitive suī, dative sibi.

-

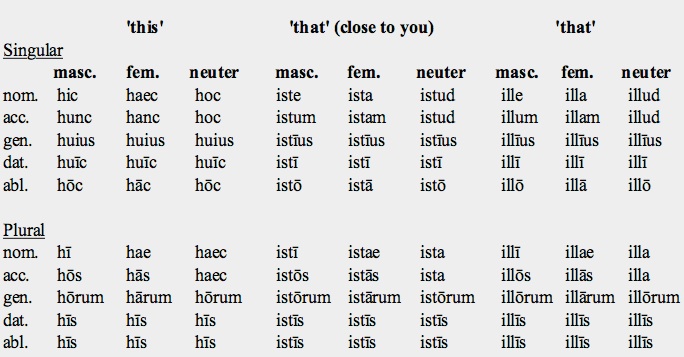

Demonstrative pronouns recognize a three-way contrast: close to the speaker, close to the hearer, distant from both speaker and hearer:

-

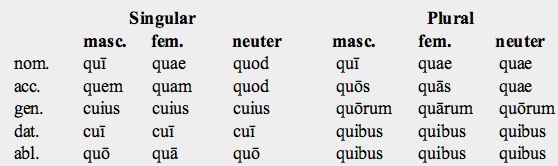

Relative and interrogative pronouns are the same except in a) the nominative singular, masculine and feminine, b) nominative-accusative singular neuter. The declension of the relative pronoun is:

-

The interrogative pronoun differs from the relative in the following forms: quis (nominative singular m/f.), quid (nominative-accusative neuter).

-

Most indefinite pronouns derive from the interrogative and relative ones: quis (‘any one, some one’), quispiam (‘some one’) quīdam (‘a certain one’), etc.

-

•compounds: nominal compounds were an original feature of Latin but their use increased substantially by Greek influence. One type includes a numeral or a negative particle as first element (e.g. in) and a noun as second element. Other compounds have a noun as first element and an agent as a second, and others combine a noun + adjective, noun + dependent genitive or dependent genitive + noun.

-

Verbal

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p

-

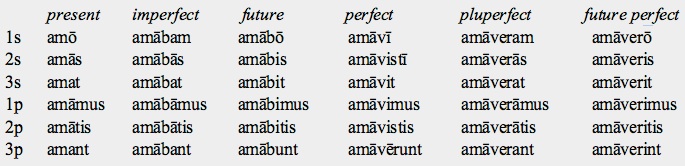

•tense: Latin has six tenses built from two separate stems. The present, imperfect and future belong to the present stem. The perfect, pluperfect and future perfect belong to the perfect stem. The imperfect tense describes ongoing events in the past, and the perfect tense completed actions.

-

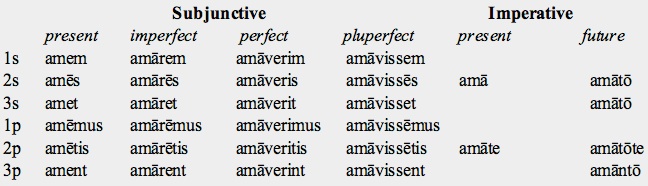

There are four conjugations classified according to the form of the present infinitive: the first conjugation has infinitives in -āre, the second in -ēre, the third in -ere and the fourth in īre. We show here the complete conjugation of amāre (‘to love’), a verb of the first conjugation.

-

•aspect: imperfective, perfective.

-

•mood: indicative (all six tenses), subjunctive (present, imperfect, perfect, pluperfect) and imperative (present, future).

-

•voice: active, passive.

-

•non-finite forms: they include participles, infinitives and verbal nouns.

-

‣participles: present active, future active, perfect passive, future passive.

-

The last one is a specialized participle, called also gerundive, denoting necessity or obligation.

-

present active: amāns ('loving)

-

future active: amātūrus ('about to love')

-

perfect passive: amātus ('loved')

-

future passive: amandus ('to be loved')

-

‣infinitives: Latin has six infinitives, two of which are formed with an auxiliary verb plus a participle (future active, perfect passive). A third infinitive (future passive) is formed by a combination of the supine (a verbal noun) + the passive infinitive of the verb to go. The other three infinitives (present active, perfect active, present passive) are independent formations.

-

present active: amāre ('to love')

-

perfect active: amāvisse ('to have loved')

-

future active: amātūrus esse ('to be about to love')

-

present passive: amārī ('to be loved')

-

perfect passive: amātus esse ('to have been loved')

-

future passive: amātum īrī ('to be about to be loved')

-

‣verbal nouns: gerund and supine. The supine is used only in the accusative and ablative cases, especially to denote purpose.

-

gerund: amāndum

-

supine: amātum

Syntax

Neutral word order in Latin tends to be Subject-Object-Verb (SOV), though it is frequently altered for emphasis and style. Unlike typical SOV languages, Latin is mostly head-initial: adjectives and relative clauses follow the head-noun, and it uses prepositions instead of postpositions. These features suggest that Latin was in a transitional phase towards an SVO order, a trend that culminated in the Romance languages which are all of the SVO type.

Adjectives agree in number, gender, and case with the noun they qualify, and verbs agree in number and person with their subjects.

Lexicon

Latin was rather conservative, preserving a number of Indo-European lexical roots that had been lost in other languages of the family. Nevertheless, it was open to outside influence. First, from other neighboring Italic languages and Etruscan, and later from Greek. The latter contributed many words about professions and trades, technical terms in the fields of grammar, philosophy and medicine, as well as Christian terminology.

Basic Vocabulary

one: unus

two: duo

three: tres

four: quattuor

five: quinque

six: sex

seven: septem

eight: octo

nine: novem

ten: decem

hundred: centum

father: pater

mother: mater

brother: frater

sister: soror

son: filius

daughter: filia

head: caput

eye: oculus

foot: pes/pedis

heart: cor

tongue: lingua

Key Literary Works

Annales (Annals). Ennius (239-169 BCE)

An epic poem telling the history of Rome, the first to adopt the dactylic hexameter from Greek epic into Latin poetry. The Annals became a text for Roman schoolchildren, eventually supplanted by Virgil's Aeneid. About 600 lines survive.

Comedies. Plautus (254-184 BCE)

These comedies of intrigue, written in verse, were sung accompanied by reed pipes. Only twenty-one of Plautus' comedies have survived. Though free adaptations of Greek plays, Italian towns and Roman laws and institutions are mentioned in them. With him a true Roman drama in Latin was established.

Comedies. Terence (195-159 BCE)

Terence wrote six verse comedies: Andria (The Andrian Girl), Hecyra (The Mother-in-Law), Heauton Timoroumenos (The Self-Tormentor), Eunuchus (The Eunuch), Phormio, Adelphoe (The Brothers). In his plays Terence eliminated the explanatory prologues and the actor's direct address to the spectators achieving a more realistic atmosphere.

Epistulae (Letters). Cicero (106-43 BCE)

Cicero wrote philosophical and political treatises, books of rhetoric, discourses and letters. 835 letters addressed by him to friends and relatives survive. Besides their literary value, they are also important from a historical point of view.

De Bello Gallico (On the Gallic War). Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE)

A narrative of the campaigns that allowed the author to conquest Gaul, on behalf of Rome, it culminates with the victory over the Gallic army led by Vercingetorix in 52 BCE. Written shortly after this event, De Bello Gallico is our only direct source about Celtic Gaul. Sober and elegant in style, it is also a unique example in Antiquity of a great general telling about his own military operations.

De Bello Civile (The Civil War). Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE)

Intended by Caesar to be a justification of his decision to take arms against Roman authorities, it is an account of the long conflict that opposed Caesar to Pompeius, describing its battles and the psychology of many of its protagonists.

De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things). Lucretius (95-52 BCE)

A long poem on a scientific subject which is didactic and at the same time moralizing. It was written for Memmius, the poet's patron, and in it Lucretius try to explain the principal doctrines of Epicurean physics. The poem is divided into three parts with two books each. Books 1 and 2 deal with the microcosm of the atom; 3 and 4 describe the Epicurean doctrine of the soul, the senses, the mind and the will; 5 and 6 deal with the macrocosm of the Universe.

Aeneidos (Aeneid). Virgil (70-19 BCE)

This famous epic poem tells the legendary story of the founding of Rome by Aeneas, a Trojan prince who after the Trojan War settles in Latium. Inspired by both the Illiad and Odyssey, it acquired the status of a national work by its heroic character and by its exaltation of the Augustan age.

Carmina (Odes). Horace (65-8 BCE)

Less than a hundred short lyric poems, inspired by Greek models, encapsulating the poet's personal world.

Epistularum Libri (Epistles). Horace (65-8 BCE)

They are letters, in verse, sent by Horace to his friends and acquaintances containing reflexions about life (his own and those of others), friendship, philosophy and art.

Ab Urbe Condita Libri (History of Rome). Livy (59 BCE-17 CE)

Written along forty years of his life, in 120 books, the history of Livy was of great scope and ambition. It starts with the foundation of Rome and ends describing contemporary events, coinciding with the close of the Republic and the establishment of the Empire. Not interested in investigating his sources, he was more keen to produce a literary and readable work than to present an accurate, scientific, history while stressing the importance of character and morality.

Metamorphoses. Ovid (43 BCE-17 CE)

A collection of mythological and legendary stories, written in hexameter verse, presented in chronological order, starting with the creation of the universe and ending with the deification of Julius Caesar. In them, the protagonists are transformed into animals or vegetables, according to their behavior but more than these 'metamorphoses' the underlying subject is that of love and passion.

Tragedies. Seneca the Younger (4 BCE-65 CE)

Works destined to the stage or to be recited in solitude, Seneca's tragedies (eight survive) have baffled many critics and readers. Disregarding tradition and innovative in style, each of them recreates a Greek mythical episode. Rhetorical and declamatory, and laying stress on horror and the supernatural, they are permeated by an omnipresent sense of evil.

Annales (Annals). Tacitus (56-120 CE)

A major historical work covering the period from 14 CE (death of Augustus and accession of Tiberius) to 68 (end of Nero's reign). Most of it has survived (40 years out of 54). It is a powerful narrative, written in a fine prose, centered on the lives of the first Roman emperors and the intrigues of the imperial court.

Saturae (Satires). Juvenal (60-138 CE)

Juvenal's sixteen satiric poems deal with life in Imperial Rome under Nerva and Trajan, and retrospectively with the horrors of Domitian's reign. In his Satires, Juvenal denounces, with fierce irony, a corrupted society and man's cruelty.

Epistulae (Letters). Pliny the Younger (61-114 CE)

More essays than real letters, most of them may have never been actually sent. Each treats a single subject developed in orderly fashion in a restrained style. Some are about public affairs and personalities, others about business or literature, others give advice…

Satyricon. Petronius (died 66 CE)

A picaresque novel, narrating the wanderings of three adventurers, which gives a portrait of some strata of Roman society in the 1st century CE. Only a portion of it has been preserved. Its most complete and famous episode is the dinner party offered by a vulgar parvenu to his friends.

Metamorphoses (The Golden Ass). Apuleus (124-170 CE)

Called by his author 'Metamorphoses', but better known to posterity as 'The Golden Ass', it is the only Latin novel that has survived entire. It tells the adventures of a young man changed into an ass, while attempting to experiment with magic, who in the end is restored to human shape by the goddess Isis. Exuberant, ludicrous, sexually explicit at times, revealing of the condition of the lower classes, and containing autobiographical elements, it also provides a glimpse of ancient religious mysteries.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Latin'. J. P. T. Clackson. In The Ancient Languages of Europe, 73-95. R. D. Woodard (ed). Cambridge University Press (2008).

-

-'Latin and the Italic Languages'. R. G. Coleman. In The World’s Major Languages, 145-170. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-'Latin'. E. Vineis. In The Indo-European Languages, 261-321. A. Ramat & P. Ramat (eds). Routledge (1998).

-

-Histoire de la Langue Latine. J. Dangel. Presses Universitaires de France (1995).

-

-Lateinische Grammatik (2 vols). M. Leumann, J. B. Hoffmann & A. Szantyr. C. H. Beck (1963-72).

Latin

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania