An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Overview. Japanese is spoken almost exclusively in the Japanese archipelago and has been, thus, physically cut off from other tongues for a very long time. In terms of size, it ranks ninth among the world's languages. It is agglutinative, employing suffixes to convey grammatical information. Though structurally very different from Chinese, it has been deeply influenced by it at the lexical level and in its writing system which is partly logographic and partly syllabic. Japanese literature is one of the most outstanding ever produced and, even if much less older than that of Chinese, can still boast of thirteen centuries of evolution.

Classification. Japanese is a language isolate, i.e., it has not been clearly linked to any language family. One hypothesis considers it to be an Altaic language with an Austronesian substratum. Its connection to Korean has been proposed though the number of cognate words is scant.

Distribution and Speakers. Almost the entire population of Japan, which is around 127 million, speaks Japanese. Some 1.5 million Japanese have migrated abroad, mainly to Hawaii and other parts of the US (nearly half a million), Brazil (380,000) and Peru (80,000).

Status. Japanese is the official language of Japan. As the population is decreasing at a rate of 0.1 % annually, the number of Japanese speakers tends to diminish slightly with time.

Varieties. Due to the mountainous terrain of the country and the consequent difficulty of communications, Japanese is very rich in dialects that are often mutually unintelligible. The dialect of the Ryukyu Islands is the most divergent and until recently was considered a separate language. Besides this, there are three main groups of dialects: Eastern, Western, and Kyushu.

The standard speech is based on the Tokyo dialect, promoted in the mass media in detriment of the regional varieties. As a result of this, of modern mobility, and of the existence of a standardized written language, a considerable degree of linguistic unification has been achieved.

Periods.

Old Japanese (up to 8th century CE)

Late Old Japanese (9th-11th c.)

Middle Japanese (12th-16th c.)

Early Modern Japanese (17th-18th c.)

Modern Japanese (19th c.-present)

Oldest Document. It is the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters), dating back to 712 CE, written partly in Chinese and partly with Chinese characters to represent Japanese words.

Phonology

Most Japanese syllables have a simple consonant-vowel structure. There are also syllables consisting in just one vowel and sequences of vowels may occur. Nasal consonants can close a syllable as well as non-nasal consonants when they are followed in the next syllable by a consonant articulated at the same place (homorganic).

Vowels (10): Standard Japanese has just five vowels which can be short or long. The difference in vowel length is phonemic. Long vowels are transliterated with a macron i.e. [a:] = ā, [o:] = ō, etc. Some dialects have additional vowels and others less than these five, their vowel systems ranging from three to eight members.

Consonants (15): The consonantal system is straightforward, having fifteen sounds. Dental consonants are often affricated or palatalized.

Accent: Japanese has a word-pitch accentual pattern based on the mora. A mora is a unit of duration which may coincide or not with a syllable. A Japanese mora may consist of: a single vowel, semivowel + vowel, consonant + vowel, consonant + semivowel + vowel, a nasal alone, the first consonant of a geminated cluster. Long vowels count as two morae. For example, mizu (‘water’) has two syllables and two morae (mi-zu), hōryūji (‘Hōryūji’) has three syllables but five morae (ho-o-ryu-u-ji), onīsan (‘older brother’) has three syllables but five morae (o-ni-i-sa-n), kitte (‘postage stamp’) has two syllables and three morae (ki-t-te).

In contrast with Chinese, in which each syllable has a specific tone, in Japanese the tone pattern is specified for the entire word. Each Japanese word has one accent or no accent at all. Thus, it is similar to English accent but while in English it is conveyed by stress (increased loudness) in Japanese it is conveyed by a change of pitch (which depends on the frequency of vibrations of the sound i.e. the degree of its highness or lowness.).

A mora may have a high (H) or a low (L) tone. Accent results from the contrast between a high-pitched and low-pitched mora. For example, accented words may have patterns H-L, HL-L, LH-L, LHH-L, LHHHL-L, etc. Thus, all accented words end in a low mora and when there is more than a H mora all the H morae are clustered together (i.e. there is only one accentual locus). Unaccented or atonic words end always in a H mora: L-H, LH-H, LHH-H, etc.

Script. The Japanese script is made up of four different writing systems:

-

1) Chinese characters or kanji.

-

2) Two kinds of syllabary or kana: hiragana (rounded) and katakana (angular).

-

3) Roman alphabet or rōmaji, introduced in the late 16th century by Portuguese and Spanish missionaries.

Kanji are used for content words, hiragana mainly for particles and inflectional endings, katakana to write foreign loanwords and some onomatopoeic expressions, rōmaji in writing foreign acronyms and in advertising. The number of Chinese characters recommended for daily use is restricted to about 2,000. Most of them have two different readings: kun (‘meaning’) and on (‘sound’). The kun reading is that of a native Japanese word while the on reading reflects the Chinese pronunciation of the character at the time of borrowing. As character borrowing began more than a millennium ago and continued through time, the current on pronunciations are usually different from the current ones in China. For example:

The on reading is generally used when two or more kanji form a compound word, often a scientific or formal term. The kun reading is usually reserved for everyday words which can stand alone, and also for verbal and adjectival roots, when they combine with hiragana. However, there are many exceptions and compounds consisting of two characters with kun readings are not infrequent as well as mixed kun-on and on-kun compounds.

Japanese is traditionally written in vertical lines from right to left but nowadays horizontal writing from left to right is also practiced.

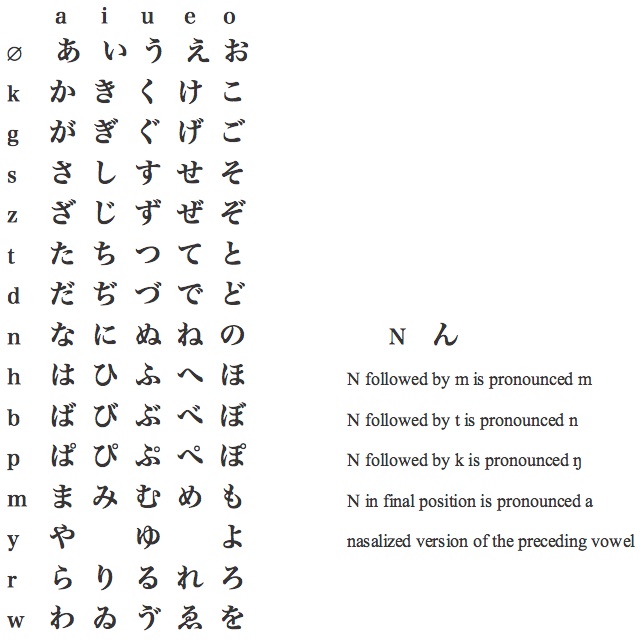

The hiragana syllabary is shown below:

Morphology

Japanese is an agglutinative language with primarily suffixing morphology. Both, verbs and adjectives inflect for tense, but they are distinguished by different tense suffixes.

Nominal. Nouns are invariable, they are not marked for person, gender or number, and case is indicated by separate particles (similar to postpositions) that indicate the relationship between a preceding nominal phrase and the rest of the sentence:

-

nominative: ga

-

accusative: o

-

dative/locative/allative: ni

-

genitive: no

-

instrumental: de

-

comitative: to

With some verbs the subject takes the dative case. With certain predicates, both the subject and the object take the nominative. Though plural marking is not obligatory, it may be expressed by reduplication, by suffixes (-domo, -gata, -tachi, -ra) or by using words like takusan ('many').

Personal pronouns are different for male and female speakers and have formal and familiar forms. They tend to be avoided in the 2nd person, being replaced by the addressee's name followed by san.

Demonstrative pronouns mark three deictic degrees: kore (this), sore (that), are (beyond that) Besides, there are demonstrative adjectives which are different from the pronouns (kono, sono, and ano, respectively). The main interrogative pronouns are: dare (who?), nani (what?), itsu (when?), dōshite (why?).

When counting, a numeral must be always suffixed by a noun classifier appropriate to the noun counted. There are some thirty classifiers of common usage, each defining a broad conceptual category: humans, big animals, small animals, birds, machines, long cylindrical objects, thin flat objects, etc.

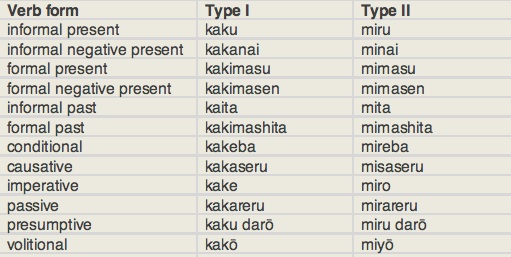

Verbal. In the Japanese verb, person, gender and number are not indicated, voice and tense are marked by suffixes placed after the verbal stem. Tense suffixes may combine with various auxiliary suffixes, often resulting in a fairly long verbal complex. Verbs are of two types (type I and type II) plus a small number of irregulars. All verbs end in u; those ending in eru or iru are (with some exceptions) of type II, the others are of type I or irregulars. The main irregular verbs are kuru ('to come') and suru ('to do'). Type I verb stems end in a consonant and type II stems end in a vowel. For example, the conjugation of kaku ('to write') and miru ('to see') is as follows:

Syntax

A typical Japanese sentence has a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) structure. For emphasis a non-subject element may be moved to the first position but the verb is always final. Topicalisation is indicated by the particle wa which may replace the nominative and accusative particles. The indirect object precedes the direct object and modifiers the modified, so that demonstratives, numerals plus classifiers, and attributive adjectives precede the noun (in that order). Subordinate clauses precede main ones, adverbs come before verbs, and auxiliary verbs follow the main ones. Postpositional particles are used instead of prepositions. Predicates show no agreement for person, number, and gender. Yes/no questions may be posed by the addition of the sentence-final particle ka in the formal language or by no in informal conversations, or simply by a change in intonation.

Lexicon

Japanese vocabulary consists of three lexical strata: native vocabulary, Sino-Japanese words, and foreign loans. Most Sino-Japanese words are compounds, developed independently in Japan, which combine Chinese words to achieve new meanings (e.g., self + manner = nature). They account for about 60 % of the total vocabulary of Japanese; in this respect the language resembles English which has a mixed Latin-Germanic lexicon. Foreign loanwords represent 5-10 %, and of them the majority is of English origin (80 %), and in a lesser proportion they come from Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch; there are also some loans from Ainu and Korean. The rest of the Japanese vocabulary comprise native words which include, besides basic items, a large number of onomatopoeic words.

Basic Vocabulary (long vowels are indicated by a macron)

one: ichi

two: ni

three: san

four: yon

five: go

six: roku

seven: nana

eight: hachi

nine: kyū

ten: jū

hundred: hyaku

father: otōsan, chichi (own)

mother: okāsan, haha (own)

elder brother: ani

younger brother: otōto

elder sister: ane

younger sister: imōto

son: musuko

daughter: musume

head: atama

eye: me

foot: ashi

heart: shinzō

tongue: shita

Key Literary Works (all dates CE)

-

712 Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters). Anonymous

-

The Kojiki is a compilation from oral tradition of myths, legends, and history. It begins with an account of the creation of Heaven and Earth, the birth of the gods and the formation of the Japanese Islands, continues with the lives of the semi-legendary Emperors of Japan, and finally deals with the historical emperors concluding with Empress Suiko who ruled in the late 6th and early 7th centuries. It was written partly in Chinese and partly using Chinese characters to represent Japanese words.

-

720 Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan). Anonymous

-

It is together with the Kojiki the oldest chronicle of Japan. Written entirely in Chinese, it begins with myth and legend before giving a chronological record of the reigns of the first emperors of Japan up to that of the late-7th century Empress Jitō. It also refers to the most powerful clans, to the introduction of Buddhism and to the Taika reforms, started in 645, which led to the first centralized government of Japan modeled on that of Tang China.

-

759 Manyōshū (Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves). Several authors

-

It is the oldest surviving collection of Japanese poetry. Though most of its 4,500 poems are tankas (31 syllables in five lines), the masterpieces of this anthology are longer poems (chōka), having up to 150 lines in length and written in the form of alternating lines of five and seven syllables. While the short tanka, that was to be the predominant form in traditional Japanese poetry, is ideal for suggestion and impressionism it doesn't allow the development of the complex subjects that the chōka does, like elegies, the celebration of the glory of the court, or the expression of personal feelings. The greatest of the Manyōshū poets was Kakinomoto no Hitomaro whose private poetry conveys highly evocative images charged with pathos. Other fine poets represented in the Manyōshū are Yamabe no Akahito, Yamanoue Okura, Ōtomo no Tabito, Ōtomo Yakamochi and Lady Kasa.

-

-

905 Kokinshū (Collection from Ancient and Modern Times). Several authors

-

This poetic anthology is the first major work using the recently created Japanese phonetic syllabary called kana. The 1,111 poems are divided into 20 books including six books of seasonal poems, five books of love poems, and single books on subjects such as travel, congratulations, and mourning. Nearly all of the poems are tankas which strive more for perfection of language and tone than originality.

-

c. 1000 Makura no shōshi (The Pillow Book). Sei Shōnagon

-

Sei Shōnagon was a lady serving in the imperial court who wrote (in prose) about things that happened to her in everyday life and about the world around her, providing a detailed and lively picture of court life in the Heian period. It is the most accomplished of the women's diaries, a genre which was popular at the time.

-

c. 1000 Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji). Murasaki Shikibu

-

This masterpiece of Japanese literature, which is considered by some as the oldest full novel, is the story of the charming, sophisticated, Prince Genji and his numerous love affairs. It gives a comprehensive view of court life in the Heian period portraying a society of refined aristocrats who were skilled in poetry, music, calligraphy, and courtship. The pleasures afforded to them were tempered by the sentiment of the fleetingness of human life.

-

12th c. Poems. Saigyō

-

Saigyō was a Buddhist priest who became one of the greatest masters of the tanka, the main Japanese form of lyric poetry. His poems are simple and direct, dealing with love of nature and devotion to Buddhism, often revealing his own experiences and emotions.

-

13th c. Heike Monogatari (The Tale of the Heike). Anonymous

-

An epic composed from oral tales chanted by blind singers accompanied by the biwa (a lute-like instrument). Based on historical facts, it relates the rise and fall of the Taira (or Heike) military clan which was finally defeated by the Minamoto clan in the battle of Dannoura in 1185.

-

1212 Hōjōki (The 10 Foot Square Hut). Kamono Chōmei

-

Composed by Chōmei while he was living as a hermit in a tiny hut on the Hino foothills to the south of the capital, Kyoto, after abandoning his life as a court poet. The work describes the desolation and ruin of the capital in contrast with the peace and joys of his life of seclusion, surrounded by natural beauty. The whole is imbued by the Buddhist thought of the impermanence of material things.

-

1307 Towazugatari (A Story Nobody Asked for). Lady Nijō

-

Translated as "The Confessions of Lady Nijō", this is a journal of a court lady, describing with honesty and great beauty the life of a woman whose lovers were priests, emperors, and statesmen. When she fell out of favor with the emperor, she was expelled from the palace and became a Buddhist nun whose wanderings are the subject of the last part of the book. This work is a testimony of the transition from an aristocratic tradition to a world ruled by the warrior class.

-

c. 1330 Tsurezuregusa (Essays in Idleness). Yoshida Kenkō

-

Kenkō served at court and observed from his privileged position the corruption and plots of the imperial family and the aristocracy. In 1324, after having abandoned his life at court, he became a Buddhist priest. In this collection of essays (from a few lines to several pages in length) he laments over the loss of old customs and the deterioration of life in his time that he saw as a decadent dark age. He also reflected about beauty and its impermanence.

1400-50 Nō Dramas. Zeami

-

Zeami and his father Kanami were the creators of the Nō drama in its present form. The Nō plays are based on short texts and are performed in small stages with no emphasis on scenery. Thanks to its imagination, the audience is able to visualize a palace, the sea or a grassy plain on the nearly empty stage. At least one actor is masked and all wear impressive costumes and their movements are highly stylized. Dance and music are an integral part of any performance. Warriors and bereaved women are frequent protagonists as well as demons and spirits, the boundaries between the natural and supernatural world being blurred.

-

1686 Kōshoku gonin onna (Five Women Who Loved Love). Ihara Saikaku

-

The protagonists of Ihara Saikaku novels belong to a merchant class become wealthy and whose tastes dominated Japanese society in the Edo period. These five tragic love stories, each one with a different heroine, are realistic tales, superbly constructed and with very convincing characters.

-

1694 Oku no hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Deep North). Matsuo Bashō

-

Bashō, one of the foremost haiku poets (a 17 syllable poem derived from the tanka), traveled frequently and this diary recounts his journey to northern Japan where he visited temples and other places of poetic interest. Mingling haikus with prose, he tried to grasp the essence of every place he visited and to delineate in a few words the people he met on the road.

1703-25 Plays. Chikamatsu Monzaemon

-

His major plays were written for the puppet theatre (bunraku), and are historical romances or domestic plays. The protagonists of the latter are the common men and women of Osaka, petty merchants, housewives, servants, prostitutes… Most of them are tragedies in which lovers condemned by a rigid society are led to suicide.

-

1776 Ugetsu monogatari (Tales of Moonlight and Rain). Ueda Akinari

-

A collection of supernatural tales influenced by Chinese ghost stories but set in Japan, mostly during the middle ages and frequently in turbulent times of civil war. Within a realistic framework appear ghosts and spirits who disturb the life of the protagonists characterized with psychological accuracy.

-

1835 Poems. Ryōkan

-

Ryōkan, a Zen Buddhist priest, poet and calligrapher, was inspired by the ancient Manyōshū, composing, besides tankas, longer chōkas which allowed him a greater freedom of expression. He lived in a hut and begged for food, recording his everyday activities in his writings. In them, he expressed the joy arising from a rich spiritual life, even in poverty. Formally, his poetry is simple and accessible without artifice, combining archaic language with contemporary matters.

1911-13 Gan (The Wild Goose). Mori Ōgai

-

This, his most popular novel, is the story of the unfulfilled love of a moneylender's mistress for a young medical student. In the background are the social changes at the end of the nineteen century and the opposition between Western and traditional Japanese culture.

-

1914 Kokoro. Natsume Sōseki

-

This novel is written in a spare prose style within a tight structure. It is centered on Sensei, who after much suffering, isolated, frustrated, feeling guilty after the suicide of his friend, and facing a changing world following the death of Emperor Meiji, commits suicide.

1915-27 Short Stories. Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

-

They stem from a wide range of sources like old tales and legends of the Heian period, events of the feudal ages or of the early era of Christian conversion in Japan. He wrote also satyrical fables and psychological stories of contemporary daily life. They are told with detachment, in a concise, feverish, often ironic style marked by evocative and clear descriptions.

-

1936 Bokutō kidan (A Strange Tale from East of the River). Nagai Kafū

-

A novella, written late in Kafū's life, in the first person, about an aging novelist who seems to be a reflection of the author. In it he laments with nostalgia and lyricism the vanishing of traditional Japanese culture being replaced by a rapid and superficial Westernization.

-

1947 Shayō (The Setting Sun). Dazai Osamu

-

The subject of this gloomy novel, written one year before the author's suicide, is the decline of an impoverished aristocratic family. Though the communication between the characters is scarce and much is left unsaid, they are rendered vivid thanks to diverse flashback techniques (a diary, letters, a will).

-

1948 Sasameyuki (The Makioka Sisters). Junichirō Tanizaki

-

A detailed study of an upper-middle-class family living in Osaka before WWII, this novel shows the author's yearning for an irrecoverable past. The characters are genuine representatives of a Japanese merchant family, respectful of tradition but at the same time influenced by Western culture, the collision between two very different worldviews being a source of conflict.

-

1948 Yukiguni (Snow Country). Yasunari Kawabata

-

Set in a remote country inn, situated in the northern mountains of Honshu, this short novel is about the love between a local geisha and a man from Tokyo. Kawabata is not much interested in plot or character but in conveying an atmosphere, a certain mood, in creating visual and aural images, in decoding feelings and beauty.

1949-54 Yama no oto (The Sound of the Mountain). Yasunari Kawabata

-

An old man suffering from loneliness and agitated by the premonition of death is at odds with his family and only finds solace in nature and in the company of his daughter in-law, Kikuko. He regrets not to have married the woman he loved and now he feels attracted to delicate and tender Kikuko.

-

1951 Aru gisakka no shogai (The Counterfeiter). Yasushi Inoue

-

A writer accepts to compose the biography of a famous painter but, instead, he becomes intrigued and obsessed by a mediocre artist who forged his works. To discover what kind of person the forger was and what were his motivations is next to impossible as the people who new him are influenced by their own prejudices, limitations and interests.

-

1956 Kinkakuji (The Temple of the Golden Pavilion). Yukio Mishima

-

A troubled young Buddhist student, ugly and afflicted from stammering, burns down this famous Kyoto temple because he cannot tolerate its beauty.

-

1962 Suna no onna (The Woman in the Dunes). Abe Kōbō

-

An entomologist is trapped by villagers in an house located at the bottom of a sand pit. There, lives a young widow whom he is forced to help in digging sand. He vainly tries to escape but in the end he is reconciled with his fate. This novel is a metaphor of the human condition, in which the need to escape from the meaningless repetition of everyday activities is followed by resignation and, finally, adaptation when living becomes a habit, something involuntary.

-

1966 Kuroi ame (Black Rain). Masuji Ibuse

-

Based on diaries of the victims and interviews, Ibuse tells the story of a woman who suffered the effects of the radioactive black rain caused by the Hiroshima bombing. With the gentle humor that characterizes his writings the author tries to soften the horror of the subject while revealing the long-term human suffering.

-

1967 Manen gannen no futtōbōru (The Silent Cry). Kenzaburo Ōe

-

Two very different brothers return to the village of their childhood to sell their family home but they end confronting each other over their family history. Two eras are contrasted, that of their ancestors and that of the early 1960's.

-

1989 Kōshi (Confucius). Yasushi Inoue

-

In this novel, a fictionalized account of the life of Confucius, Yanjiang, one of his disciples, narrates the fourteen years he spent near the Master, and through his words gradually emerges Confucius's image. An exhaustive research and historical accuracy give Inoue's writings a flavor of authenticity.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-A Reference Grammar of Japanese. S. E. Martin. Yale University Press (1975).

-

-The Japanese Language through Time. S. E. Martin. Yale University Press (1987).

-

-The Japanese Language. R. A. Miller. University of Chicago Press (1967).

-

-The Languages of Japan. M. Shibatani. Cambridge University Press (1990).

-

-Japanese. S. Iwasaki. John Benjamins (2002).

-

-The Japanese Writing System. Available at: http://www.cjvlang.com/Writing/writjpn.html

-

-Guide to the Japanese Writing System. Kanji Dictionary Publishing Society. Available online at:

-

-A History of Japanese Literature (3 vols). S. Kato. Kodansha International (1981).

Japanese

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania