An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification and Overview. Korean is a language isolate with no clear connections to any other. It is non-tonal and polysyllabic. It might be related to the Altaic family, and especially to its Tungusic branch. Korean syntax is quite similar to that of Altaic languages, and also resembles Japanese syntax. Korean morphology shares some broad features with Japanese: agglutinative morphology (primarily suffixing), invariable nouns, case indicated by postpositional particles, use of noun classifiers. However, the sound systems of both languages are very different, as well as their lexicons. Korean has been deeply influenced by Chinese in its vocabulary, incorporating a massive amount of words from it.

Distribution. Korean is spoken in the Korean Peninsula, divided politically between North Korea and South Korea. Also, by the Korean diaspora in several countries, particularly in China, Japan, Russia and Central Asia (Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan) as well as in the United States.

Speakers. Korean is spoken by about 79 million people, of which 75 million live in both Koreas. More than 4 million are expatriates:

South Korea

North Korea

China

USA

Japan

Uzbekistan

Russia

Kazakhstan

50,000,000

25,000,000

2,000,000

1,100,000

700,000

183,000

150,000

103,000

Status. Korean is the official language of South Korea (Republic of Korea) and North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea). It is also one of the two official languages in the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in China.

Varieties. Korean has two standards. The standard language of South Korea is based on the dialect of the area around Seoul, and the standard of North Korea is based on the dialect spoken around Pyongyang. Besides discrepancies in pronunciation, the differences between the two standards are consequence of different policies: in the North there is a drive to reduce the number of Sino-Korean loanwords and to use only the romanized hangul script while the South has a more ambivalent attitude towards those issues. In addition to these two standards, Korean has several regional dialects which are quite similar to each other and mutually intelligible.

Old Korean is scantily documented by place-names, by a group of poems, called hyangga, and by vocabularies compiled by the Chinese.

Middle Korean coincides with the moving of the capital to Seoul, whose dialect became the standard language, and with the invention of an alphabetic script.

Modern Korean began with the Japanese invasion headed by Hideyoshi. It is distinguished by changes in the writing system and the emergence of a popular literature.

10th-14th c.

15th-17th c.

17th c.-

Oldest Documents

-

•the earliest records of the language are twenty-five Old Korean poems written with Chinese characters in the hyangga style. Two-thirds of them are inspired by Buddhism.

-

•lists of Korean words compiled by the Chinese from the beginning of the 12th century.

Phonology

Syllable structure. Korean syllables have a CV(C)(C) structure. Thus, clusters at the beginning of a syllable are not allowed. The possible final consonants are p, t, k, m, n, ng, or l.

Vowels (10). Korean has a ten-vowel symmetrical system composed by five front and five back vowels:

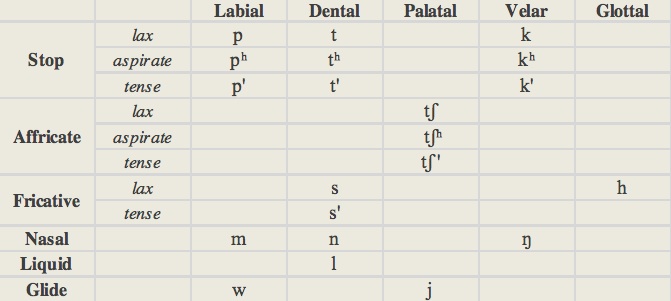

Consonants (21). Korean stops and affricates are divided into three series: lax, aspirate and tense. Consonants of the three series are voiceless, but the lax ones become voiced when they occur between two voiced sounds. Lax consonants are produced without glottal tension and the tense ones with it. Aspirated stops are produced with stronger aspiration than English aspirated sounds. The liquid sound [l] becomes a flapped [r] between vowels and in word-initial position.

Before other obstruents and in word-final position, all stops are pronounced lax. When there is a consonant cluster in word-final position, only one consonant is pronounced. Consonants are frequently assimilated to the following sound. For example k, t, p are pronounced before nasals as [ŋ], [n], [m].

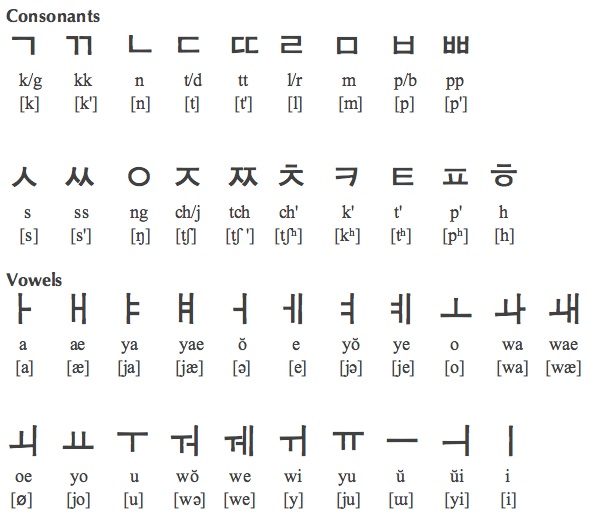

Script and Orthography. Modern Korean is written in an alphabetic script, called Hangul, commissioned by King Sejong the Great in 1443. It has 40 signs which include 10 for simple vowels, 11 for diphthongs and 19 for consonants (the two glides have no independent signs and are represented as diphthongs). Of the 19 consonantal signs, 5 are "double consonants" i.e. tense consonants represented by doubling the corresponding lax one.

The symbols of each syllable are grouped into a square block resembling, superficially, a Chinese character. The first element in the block is the initial consonant; if the syllable begins with a vowel, a small circle serves as a zero initial. Then follows, either to the right or below (or both) the vowel nucleus. At the bottom an optional final consonant or a cluster of two consonants may be added. In South Korea, words of Chinese origin are, sometimes, written with Chinese characters which alternate, in the same text, with others written in Hangul.

Two transliteration schemes are currently in use: the McCune-Reischauer system (used here) and the Yale system. Below, the Hangul alphabet is shown with the McCune-Reischauer transliteration and its phonetic equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet between square brackets.

Note: In the McCune-Reischauer system, used here, some consonants have two alternative transliterations to reflect the actual pronunciation e.g., g, d, b between voiced sounds or otherwise k, t, p.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Nouns, adjectives and pronouns are not inflected.

-

•gender: is not marked.

-

•number: plurality of nouns can be marked by -tŭl or by a numeral. When a numeral is present, a noun classifier is attached to the numeral and a plural marker is not required. Unusually, the plural marker can be attached to adverbs in subjectless sentences when number is not otherwise expressed.

-

•classifiers: Korean, like Chinese and Japanese, when counting persons, animals or objects uses classifiers appropriate to the noun counted. They identify several semantic/conceptual groups like: human, animal, plant, shape, arms, clothes, books/printed materials, and buildings. The numeral + classifier is placed most frequently after the noun but it can also precede it. In the latter case the genitive particle ŭi is inserted between the numeral + classifier and the noun. For example, "two bottles of beer" may be expressed in either of the following ways:

-

1) maekcu tu-pyŏng maekcu: beer (noun); tu: two (numeral); pyŏng: bottle (classifier)

-

2) tu-pyŏng ŭi maekcu ŭi: of (genitive particle)

-

•case: is indicated by postpostional particles placed immediately after the noun. Seven cases are distinguished: nominative (i following a consonant or ka following a vowel), accusative (ŭl/lŭl), genitive (ŭi), dative (e/eke), locative (esŏ), instrumental (ŭlo/lo), comitative (kwa/wa).

-

•pronouns: personal pronouns have formal and familiar forms. Demonstratives are used for the 3rd person.

-

Demonstratives distinguish three degrees of spatial relationship: i (‘this’), kŭ (‘that’), chŏ (‘that yonder’). A similar deictic system expresses location: yŏki (‘here’), kŏki (‘there’), chŏki (‘yonder’).

-

The interrogative pronouns are nugu (‘who?’), muŏs (‘what?’), ŏnje (‘when?’) and myŏch’ (‘how many?’). Korean has no relative pronoun.

-

Verbal. Korean verbs are of four types: action verbs, descriptive or stative verbs (akin to adjectives), existential, and copulas (which allow a non-verb to take verbal endings). Existential verbs are conjugated like action verbs, and copulas like stative verbs. Verb morphology is agglutinative and almost exclusively suffixing. Around 40 different suffixes can be attached to the verb, distributed in several positions. The verbal complex consists of stem + honorific marker + tense marker + formal marker + mood marker. Person and number are not marked on the verb; they are indicated by subject pronouns.

-

✴The honorific marker (ŭ)si may be added to express respect to the subject of the verb.

-

✴The tense markers are: ŏss (past), ŏss-ŏss (past anterior), kess (future). The present has no tense marker (zero suffix).

-

✴The formal markers are: yo to convey politeness to the hearer and sŭpni/pni to address somebody of a higher social status.

-

✴The mood morphemes are at the end of the verbal complex. The main ones are: ta (declarative), la (imperative), cha (propositive), kka (interrogative).

Passive and causative verbal forms can be derived by adding suffixes immediately after the stem:

-

✴The passive voice suffix may be attached only to transitive verb stems and has four allomorphs: -i-, -hi-, -li-, -ki-.

-

✴The causative suffix may be attached to verbs of any kind (with the exception of the copula) and has several allomorphs: -u-, -i-, -ki-, -hi-, -hu-, -li-. The occurrence of a particular allomorph is determined by the stem ending and even if some causative allomorphs are identical to the passive ones they are sometimes differentiated by their phonetic environment, e.g. the passive -i- may occur after p’-ending stems while causative -i- cannot, thus tŏp’i (‘to be covered’) is unambiguously passive. Besides, passive and causative verbs are clearly distinguished in an actual sentence because passive ones don’t have an object while causatives have one or more.

Progressive sentences are formed by placing the auxiliary verb construction -ko iss- after the main verb stem. This progressive construction may occur not only with action verbs but also with stative ones, and even with imperatives. -Ko is a concatenating element (a complementizer) that is suffixed to the main stem while the copula iss is suffixed with an appropriate tense marker. For example:

-

✴mŏk-ko iss-ta (‘is having’). Present progressive tense

mŏk: stem, ko: concatenator, iss: auxiliary stem, present marker: zero, ta: declarative marker

-

✴il-ko iss-kess-ta (‘will be reading’). Future progressive tense

il: stem, ko: concatenator, iss: auxiliary stem, kess: future marker, ta: declarative marker

Other aspects, like inchoative (beginning of an action), habitual, iterative (repeated action), perfective (completed action), may be also expressed by auxiliary verb constructions including a complementizer suffixed to the main verb stem plus an appropriate auxiliary verb.

Negation is expressed, in declarative and interrogative sentences, by adding the prefixes an or mos to the verbal stem; an is a general negator and mos is equivalent to 'cannot'. In negative imperatives the particle ma is employed.

Syntax

The basic word order in transitive sentences is Subject-Indirect Object-Direct Object-Verb (SOV). It is quite flexible except for the position of the verb which must always be final. Modifiers, such as adjectives, demonstratives and genitives, precede head nouns. Korean predicates do not agree in number, person or gender with their subjects. Sentences without first and second person subjects are allowed as long as the subject is implicit in the discourse. Deletion of third person subjects is rarer. In Korean there are no articles, and definiteness is not, usually, distinguished though sometimes it is indicated by demonstratives. Syntactic relations between words are expressed mainly by postpositional markers.

Lexicon

More than half of Korean words are of Chinese origin, received directly from Chinese or through Japanese. They include everyday words and learned terms. In contrast, Korean has adopted few native Japanese words. English has contributed scientific and technical words as well as some ordinary ones. Other European languages, like French, Spanish and Portuguese have made a lesser impact.

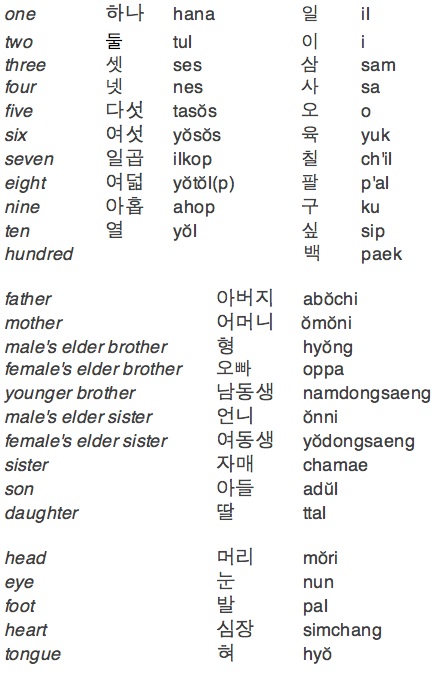

Basic Vocabulary. There are two sets of Korean numbers: the native one (first column) and the Sino-Korean (second column):

Key Literary Works (all dates CE)

-

1447 Yongbi ŏch'ŏn ka (Songs of Flying Dragons). Anonymous

-

One of the first works of Korean literature written in Hangul, it is a compilation of poems, meant to be sung, praising the founder of the Chosŏn kingdom. They are in the akchang style, based on a line of alternating groups of three or four syllables.

-

1447 Wŏrin ch'ŏngang chigok (Songs of the Moon's Reflection on a Thousand Rivers).

-

Anonymous

-

A series of poems compiled by King Sejong in praise of Buddha's life which is, like the previous, one of the first works of literature written in Hangul script.

1560-93 Sijo poems. Chŏng Ch'ŏl

-

Chŏng Ch'ŏl mastered two classical verse forms, the longer philosophical kasa, and the shorter lyrical sijo (three-line poems of 14-16 syllables each). Frequently at odds with the political establishment, some of his sijo poems deal with his experiences in public life while others are about retirement, life in the countryside, and mortality.

-

1687 Kuun mong (The Cloud Dream of the Nine). Kim Manjung

-

A didactic and philosophical novel, set in ninth century China, protagonized by two contrasting characters: a Buddhist monk, who lives in a spartan cell praying and eating frugally, and a succesful Confucian bureaucrat, who passes examinations, triumphs in war, and is married to eight women.

1797-1805 Hanjung nok (Record of Sorrowful Days). Lady Hong

-

It is an autobiographical memoir by a princess of the imperial court relating her tragic life marred by a succession disput.

-

1917 Mujŏng (The Heartless). Yi Kwangsu

-

Considered the first modern Korean novel, "The Heartless" is the story of a love triangle during the Japanese occupation. A young English teacher in Seoul is attracted by two women, one has had a Western education and plans to continue her studies in the United States, the other has a talent for music and has been raised in the traditional Confucian manner. These characters serve to develop the subject of national identity and the challenges presented to Korea by modern culture.

-

1925 Kamja (Potato). Kim Tongin

-

A short story about an ill-fortuned woman who is sold to a widower and, being ignored by him, has to fend by herself falling to the lowest class of society.

-

1926 Nim ŭi ch'immuk (The Silence of Love). Han Yongun

-

In his eighty-eight meditative poems Han resorted to Buddhist thought to cope with the Japanese invasion of his country.

-

1941 Paengnoktam (White Deer Lake). Chŏng Chiyong

-

Modernist poems about the intimate connection between man and nature.

-

1946 Yuksa sijip (Poems by Yuksa). Yi Yuksa

-

Yi Yuksa was engaged in the Korean resistance movement against Japanese colonialism and died in prison. This book of poems, his only one, published posthumously, reflects the permanent tension of his life and his nationalist sentiment.

-

1978 Changma (The Rainy Spell). Yun Hŭnggil

-

It tells about the encountered feelings of two mothers, living under one roof, whose sons are on the opposing war camps during the Korean War and of their child grandson who becomes innocently entangled in the conflict.

1964-94 T'oji (The Land). Pak Kyŏngni

-

A twenty-one volume novel, written in the course of thirty years, narrating the turbulent history of Korea between 1897 and 1945. The story follows four generations of a family of wealthy landowners who experience the dissolution of traditional society and the influx of Western materialism, followed by Japanese domination and the struggle for independence.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-The Korean Language. Ho-Min Sohn. Cambridge University Press (1999).

-

-A Reference Grammar of Korean. S. Martin. Tuttle, Rutland and Tokyo (1992).

-

-'Korean'. Nam-Kil Kim. In The World's Major Languages, 765-779. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-The Making of the Korean Language. Chin-Wu Kim. Center for Korean Studies, University of Hawaii (1974).

Korean

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania