An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Iranian, Northwestern Iranian (which also includes Balochi and several languages of central Iran).

Overview. Reflecting the political fragmentation of the Kurds, who lack a national state, Kurdish is a collection of (often not mutually intelligible) dialects, more than a single language. This major Iranian tongue is spoken in a large contiguous area of the Middle east including eastern Turkey, Syria, northern Iraq, western Iran and parts of the Caucasus region. Kurdish, in all its varieties, resembles Persian in many ways, due in part to their common origin but also because of the direct influence of the latter, the most prestigious literary and cultural language of the area for a long time.

Distribution. Eastern Turkey, Syria, northern Iraq, western Iran, the Caucasus region (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia), Afghanistan and Central Asia (Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan). There are many Kurdish expatriates in Germany and France.

Speakers. Between 25-28 million in the following countries:

Turkey

Iran

Iraq

Syria

Germany

Afghanistan

Armenia

Azerbaijan

France

Lebanon

Georgia

Turkmenistan

Kazakhstan

11,000,000

7,000,000

4,000,000

2,000,000

600,000

200,000

100,000

100,000

100,000

90,000

60,000

40,000

25,000

Status. Kurdish is one of the two official languages of Irak (the other is Arabic). In Iran it is not used for education and in Turkey it has been subject of severe restrictions which have been recently relaxed. In Syria, the publication of Kurdish material is forbidden.

Varieties. As the Kurds do not have their own state and are dispersed in many countries, there is no standard language and no single writing system. The main dialectal groups are: Northern Kurdish (Kurmanji), Central Kurdish (divided into Sorani, Mukri and Sennei subgroups) and Southern Kurdish.

-

‣Northern Kurdish is the most widely spoken form of Kurdish (about 20 million) predominating in eastern Turkey and Istanbul, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and the Caucasus.

-

‣Central Kurdish is spoken by 5 million people in northern Iraq (called Sorani) and neighboring areas of Iran (called Mukri), as well as in Iranian Kurdistan (called Sennei).

-

‣Southern Kurdish is spoken by about 3 million people in the Kermanshah province of western Iran and adjacent regions of eastern Iraq.

These three main dialectal groups are quite different from each other and, in particular, Northern Kurdish is not mutually intelligible with the other groups. Sorani and, especially, the dialect of the city of Sulaymaniyah in northeastern Iraq is considered by many as the standard language.

Oldest Documents

late 17th c. Mem ū Zīn, an epic poem composed by Ahmadī Khānī.

1787. First Kurdish grammar, authored by the catholic missionary Maurizio Garzoni.

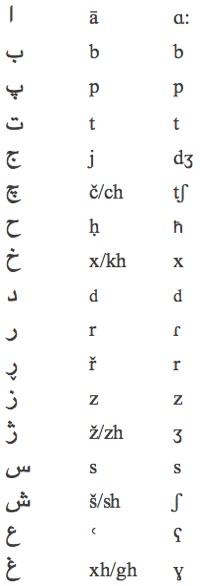

Phonology

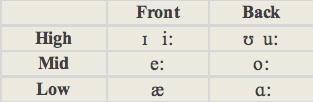

Vowels (8). Sorani Kurdish has three short and five long vowels. It has retained the Middle Iranian vowels o:, e:, which in Persian have merged with u: and i:.

[ɪ] is slightly lower and more centralized than [i:]; [ʊ] is slightly lower and more centralized than [u:].

[æ] is pronounced [ɛ] or [ə] in certain contexts (allophones).

Consonants (29). Kurdish stops-affricates and fricatives are articulated at four main points (labial, dental, palatal, velar) grouped in pairs of contrasting voiceless and voiced varieties. Besides, it has a number of back sounds (uvular, pharyngeal and glottal). The liquids consist of two rhotics (r-like sounds) and two laterals (l-like sounds). One rhotic is a flap [ɾ], the other is a rolled r or trill [r].

Stress: all nouns and adjectives are stressed on the final syllable. The definite suffix is also stressed. Conjugated verbs without prefixes are stressed on the final syllable of the stem; if there is a prefix it generally carries the stress. The infinitive is stressed on the final syllable.

Script and Orthography

Kurdish has been, and still is, written in a variety of scripts. In Turkey and Syria a modified Turkish script is used nowadays but in the past the Armenian, Cyrillic and Latin alphabets have been employed. In Iraq and Iran, Kurdish is written with a version of the Arabo-Persian script implemented after World War II. In the republics of the former Soviet Union Kurdish is written in Cyrillic.

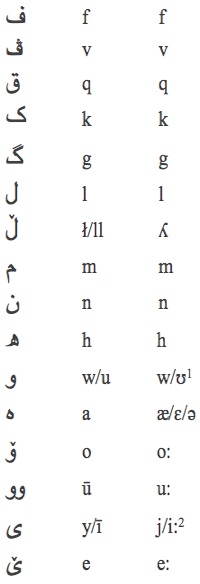

In the first column the Kurdish Arabo-Persian alphabet is shown, in the second its transliteration into the Latin alphabet, and in the third one the equivalents in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Long vowels are transliterated with a macron.

1. w after a vowel, ʊ after a consonant.

2. short i [ɪ] has no symbol.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Nouns are marked for number and definiteness by suffixes.

-

•gender: there is no grammatical gender.

-

•case: most case distinctions have been lost but some nouns have a vocative case.

-

•definiteness and number: indefinite and definite nouns and adjectives are distinguished by suffixes.

-

The bare stem may signify indefinite non-specific singular or a generic plural. The definite suffix is -aka (-ka after some vowels) and the indefinite one is -ēk (-yēk after vowels).

-

The usual plural marker is -ān which is placed after the definite article if present. For example: žinakān (‘the women’).

-

When a numeral is used it is followed by a noun classifier which itself is followed by the singular noun. The most common classifiers are nafar for people, sar for animals and dāna for things. For example:

-

hašt dāna ktāw (‘eight books’)

-

se sar mař (‘three sheep’)

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

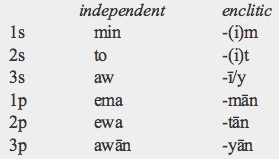

Personal pronouns may be independent or enclitic and distinguish three persons and two numbers. The enclitic ones are used as possessive markers suffixed to the noun and also as direct object markers in the present indicative and present subjunctive.

-

Demonstrative pronouns show one-level contrast (proximal-distal): ama (‘this’), amāna (‘these’), awa (‘that’), awāna (‘those’). When they are used as demonstrative adjectives they envelop the noun:

-

red: plural marker

-

brown: demostrative

-

-

Note: a becomes ya after vowels.

-

The interrogative pronouns and adverbs are: kē (‘who?’), čī (‘what?’), kām (‘which?’), kwē (‘where?’), čōn (‘how?’), čand (‘how many?’).

-

The relative pronoun is ka (‘who/which/that’). Relative clauses are often introduced by it but it can be omitted (in contrast to Persian), particularly when it functions as the object the clause.

-

•izāfa construction: two nouns in genitive relationship are linked by the letter i, possessed preceding possessor. For example, malā i mizgawt (‘mullah of the mosque’). Attributive adjectives are also linked to their nouns by i: hotel i bāš (‘good hotel’). When the noun-adjective construction is definite or is enveloped by demonstratives the linking vowel changes to a: hotel a bāšaka (‘the good hotel’).

-

Verbal. The verbal system is typically modern Iranian, with three-stem basic tenses: present-imperfect, past, and perfect. The conjugation of transitive verbs in the several past tenses is different from that of the intransitive ones. In the former there is ergativity (see syntax). Compound verbs combining a nominal and a verbal element are frequent.

-

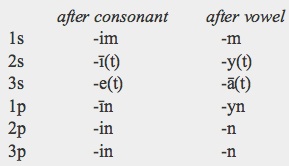

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3sm, 3sf; 1p, 2p, 3pm, 3pf. Personal endings for intransitive verbs are the same in all tenses. They are shown in the table.

-

•aspect: perfective, imperfective.

-

•mood: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, imperative.

-

•tense: present, imperfect, past, present perfect, past perfect.

-

The present is employed to express an habitual action, a progressive action and the future. The imperfect expresses an habitual or progressive action in the past. The present and imperfect take the same prefix dá-; the former uses the present stem and the latter the past stem. The present stem is frequently unpredictable, the past stem is obtained from the infinitive by dropping its final in (see table below).

-

The simple past of intransitive verbs is formed by adding the personal endings directly to the past stem. In transitive verbs there is an ergative construction and the same happens in other past tenses (see syntax).

-

The present perfect expresses a completed action relevant to the present while the past perfect refers to a remote action or to an action completed before another past action. The former is based on the perfect participle which is equal to the past stem + ū (after consonant) or w (after vowel). The latter is formed with the past stem + i + the past tense of būn ('to be').

-

-

For example, the affirmative and negative conjugation of kawtin ('to fall') in the 1st person singular is:

-

black: stem (present kaw, past kawt)

-

orange: mood/tense

-

marker

-

red: auxiliary verb būn

-

blue: personal endings

-

green: negative marker

-

brown: passive marker

-

The present subjunctive is the same as the present indicative but its prefix is bí-. It is used for exhortations or as an equivalent of the English 'should', or to express wish, necessity or ability. The past subjunctive is formed like the past perfect but instead of the past tense of būn, the present subjunctive of būn is added. It is used after all constructions that take subjunctive complements when the complement is in the past.

-

The conditional expresses hypothetical or unrealized conditions and has two forms. Conditional I is formed with the subjunctive prefix bí- + the simple past conjugation + āya. Conditional II is formed with the subjunctive prefix bí- + the past subjunctive conjugation but based on bā (a variant of the subjunctive of būn).

-

The imperative is formed from the present stem of the verb plus the prefix bí-. In the 2nd singular it has no personal ending but if the stem ends in a consonant the suffix -a is added. The 2nd person plural is marked with the suffix -n/-in (it is identical to the 2nd plural of the present subjunctive).

-

Negative conjugations are marked by ná-. This prefix cannot coexist with the particle bí; if there is one it is replaced by ná.

-

Passive forms can be made from the present stem of transitive verbs by adding re for the present (indicative and subjunctive) or rā for the past and perfect tenses.

-

•voice: active, passive. Central and Southern Kurdish have passive formations in re or ye (present), rā or yā (past). A causative is made with the suffixes -ēn/ān(d).

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, perfect active participle, past passive participle. The perfect active participle is formed with the past stem plus -ū/-w. It serves to form the present perfect but it can also be used adjectivally or nominally. The past passive participle is formed from the past passive stem in rā plus the suffix -w.

Syntax

Kurdish exhibits the typical Modern Iranian Subject-Object-Verb word order. Syntactical relations are indicated mainly by prepositions and circumpositions. It has split ergativity conditioned by transitivity and tense. As we have seen, in intransitive verbs the subject is marked by personal endings in all tenses and moods. With transitive verbs, occurs the same in the present, but in past tenses the agent is encoded by enclitic personal pronouns. These are attached to the leftmost component of the verbal clause after the subject position: direct object, the first element of a compound verb (noun, adjective, directional particle), prefixes or, in the absence of any other component, they are placed after the stem itself. For example, past tenses of the transitive verb xwārdin ('to eat') are:

-

imperfective: dámānxwārd We were eating (it).

-

-

negative past: námānxwārd We didn't eat (it).

-

-

affirmative past: xwārdmān We ate (it).

black: stem, blue: personal enclitic pronoun 1st plural, orange: imperfective marker, green: negative marker.

When the agent precedes the verbal stem, the logical object is expressed by the same personal endings of intransitive verbs attached to the past stem which now express the object and not the subject. For example, the verb āgā-kirdin (to inform).

-

āgāy kirdim

-

aware-he made-me

-

He informed me.

-

āgāy kirdīn

-

aware-he made-us

-

He informed us.

black: stem, blue: personal enclitic pronoun 3rd singular, red: personal endings.

Direct-object pronouns of verbs in the present indicative and the present subjunctive mood are enclitic personal pronouns attached to a modal prefix or to the negative prefix, or if the verb is a compound to its first element:

-

dáyānbīne He sees them.

-

-

náydanāsim I don't know him

-

-

bāngim dákan They are calling me

-

a call-me making-they

black: stem, brown: direct-object pronoun, blue: personal endings (subject markers),

orange: present marker, green: negative marker. Ka is the present stem of kirdin (to do/make).

Lexicon

Kurdish has experienced a great influx of Persian and Arabic words.

Basic Vocabulary

one: yek

two: dū

three: se

four: čwār

five: penj

six: šaš

seven: ḥawt

eight: hašt

nine: no

ten: da

hundred: sad

father: bāw

mother: dāyik/mak

brother: birā

sister: xwaišk

son: kur

daughter: keč, dot

head: ser

eye: čav

foot: pe

heart: dil

tongue: ziman

Key Literary Works (forthcoming).

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Kurdish'. E. N. McCarus. In The Iranian Languages, 587-633. G. Windfuhr (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-Sorani Kurdish. A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings. W. M. Thackston. Available online at http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~iranian/Sorani/index.html

-

-Kurmanji Kurdish. A Reference Grammar with Selected Readings. W. M. Thackston. Available online at: http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~iranian/Kurmanji/index.html

-

-A Kurdish Grammar. Descriptive Analysis of the Kurdish of Sulaimania. E. N. McCarus. American Council of Learned Societies (1958).

-

-Grammaire Kurde (dialecte kurmandji). D. Bedir Khan & R. Lescot. Adrien Maisonneuve and Kurdisches Institut (1970).

-

-Manuel de Kurde: Kurmanji. J. Blau & V. Barak. Harmattan (1999).

Kurdish

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania