An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Name Origin: Sindhi derives from the Sanskrit word sindhu, that means 'river'. Sindhu was also the proper name of the Indus River.

Classification: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Modern Indo-Aryan, North-Western. Other languages of the same group are Punjabi and Kashmiri.

Overview. Sindhi is a regional Indo-Aryan language born in the western fringes of Medieval India. Developed in the lower Indus River valley, a land that experienced an early contact with Islam, it was influenced by Arabic and Persian at the lexical level and by Persian at the phonological level.

Distribution: The majority of speakers live in the Sindh province of south-east Pakistan. Within Pakistan, there are also Sindhi speakers in the southwestern Province of Baluchistan (Lasa Belo region). India has also a substantial number of speakers, especially in Gujarat, Mumbai and Pune. Sindhi speaking expatriates, from Pakistan and India, reside in the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Singapore, United Kingdom, Canada and the United States.

Speakers: There are about 29 million native Sindhi speakers of which 26 million in Pakistan and 3 million in India.

Status. Sindhi is the official language of the Pakistani province of Sindh and one of the 23 official languages of India. In Pakistan it predominates in the rural areas.

Varieties. Sindhi has six dialects: Siraiki in Upper Sindh, Vicholi in Central Sindh, Lari in Lower Sindh, Lasi in the Lasa Belo region of Baluchistan, Thari in southeast Sindh and the Jaisalmer district of India, Kacchi in Gujarat. Vicholi is the literary language and is considered the standard.

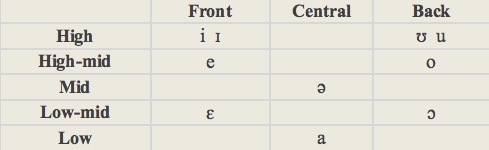

Phonology

Vowels (10). Sindhi has a ten vowel system composed of three lax and seven tense vowels. Lax vowels (ɪ, ʊ, ə) are phonetically short and tense vowels (i, e, ɛ, u, o, ɔ, a) are phonetically long. [ɪ] is slightly lower and more centralized than [i], [ʊ] is slightly lower and more centralized than [u]. All have nasal forms. Oral and nasal vowels are contrastive.

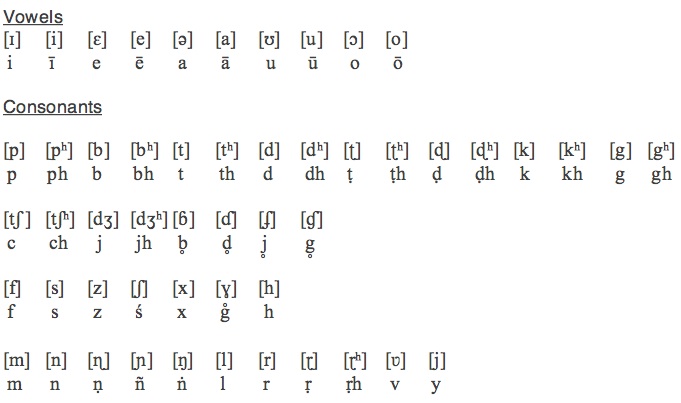

Consonants (42). Sindhi has 42 consonants in total, including 20 stops and affricates, 4 implosives, 7 fricatives, 5 nasals, and 6 liquids/glides. The stops and nasals are articulated at five different places, being classified as labial, dental, retroflex, palatal and velar.

Every series of stops/affricates includes voiceless and voiced consonants, unaspirated and aspirated, this four-way contrast being unique to Indo-Aryan among Indo-European languages (Proto-Indoeuropean had a three-way contrast only). Sindhi presents the novelty, among Indo-Aryan languages, of having implosive stops (produced by ingression of air). It also has some fricatives, rare or absent in the Indo-Aryan branch, due to the influence of Persian. [ʋ] is realized as v or w. The labial, dental and retroflex nasals as well as [l] have aspirated counterparts which some interpret as two sounds and others as one.

Transliteration scheme

In Pakistan, Sindhi is written in a modified and expanded Arabic script containing 52 letters. In India, besides this script, Devanāgarī is also employed. Here, we use the following transliteration scheme:

Morphology

-

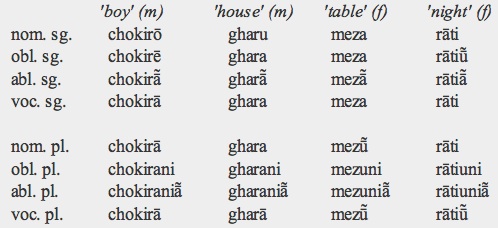

Nominal. Nouns, pronouns and some adjectives are inflected for gender, number and case.

-

•gender: masculine and feminine. Masculine nouns typically end in -ō, -u and -ū; feminine nouns end in -a, -ā, -i, -ī.

-

•number: singular and plural. Pluralization involves a change of the noun final vowel.

-

•case: direct, oblique, ablative, vocative.

-

The direct case is used for subject and direct object. The oblique case is used for nouns accompanied by postpositions which serve as markers for other syntactical functions. The ablative indicates source or point of departure. Some adjectives are indeclinable but others are inflected for gender, case and, sometimes, number.

-

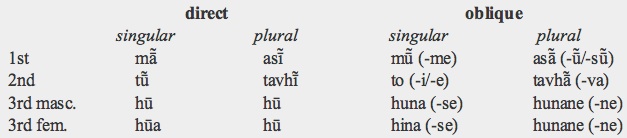

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

Personal pronouns have direct and oblique forms (independent and enclitic). They are genderless except in the 3rd person singular.

-

Forms between brackets are enclitic.

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish between proximal and distal: hī ('this' masc.), hīa ('this' fem.), hī ('these'); hū ('that' masc.), hūa ('that' fem.), hū ('those'). The distal pronoun is the same as the 3rd person pronoun.

-

The interrogative pronouns are kēru ('who?') and kehaṛo ('what?').

-

The relative pronouns, jo (masc.), ja (fem.), have so as correlative in the main clause.

-

Verbal

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p.

-

•mood: mood and tense are not completely separable in Sindhi. The presumptive, subjunctive and contrafactual are considered an integral part of the tense system. Only the imperative is considered an independent mood; it is expressed by the bare verb stem plus its own personal markers e.g. hal → halu ('go!'), halō/halijē ('go!', polite).

-

•aspect: imperfective (including habitual and continuous actions) and perfective (completed activities). They originate two stem types. The imperfective stem is formed by attaching the affix -and- to the verb root and the perfective one by adding -y- to it. Within the imperfective, Sindhi contrasts continuous and habitual aspects in the present and past tenses marking the continuous with the distinctive affix -ī-.

-

•tense: most finite-verbs combine aspect and tense. There are two aspects, imperfective and perfective, and four different forms of the verb 'to be', present, past, presumptive, subjunctive. Combined together, they produce ten aspectual tenses (the imperfective aspect has habitual and continuous forms in the present and past). Besides these, Sindhi has six additional verbal forms that lack either aspect or tense; one of them is a past conditional called contrafactual.

-

The compound tenses are formed with the imperfective or perfective participle, which agree in gender and number with the subject, plus the present, past, presumptive and subjunctive forms of the copula. The present and subjunctive copulas mark person and number while the past and presumptive copulas mark person, number and gender.

-

-

The 3rd singular forms of the copula are: present āhē, past hō, presumptive hundō, and subjunctive hujē. Another auxiliary verb is used for the unspecified present (thō) and for the past iterative (thē). The contrafactual is marked by the invariable particle hā. The continuous tenses use a second auxiliary in addition to the present copula, the verb rahaṇu ('to stay').

-

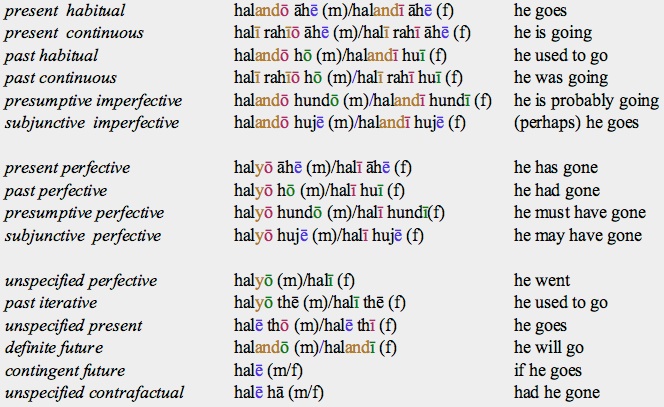

The list of Sindhi finite forms of the verbal hal (‘go’) is:

-

black: verb root; brown: aspect marker; red: gender and number concord

-

green: person, gender and number concord; blue: person and number concord.

-

•voice: active and passive. There are two passive forms. One has future sense and implies an obligation; it is formed with the affix -(i)j- e.g. sikhijaṇu ('to be learned'). The other has an imperfective aspect; it is formed with the suffix-ibō e.g. sikhibō ('being learned').

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive, adjectival future, imperfective and perfective participles, adverbial imperfective and perfective participles; the latter also known as conjunctive participle. The non-finite forms of hal (‘go’) are:

-

infinitive: halaṇu ('to go')

-

adjectival future participle: haliṇō (about to be going)

-

adjectival imperfective participle: halandō ('going')

-

adjectival perfective participle: halyalu, halyō ('gone')

-

adverbial imperfective: halandē ('as he was going')

-

adverbial perfective or conjunctive: halī ('having gone')

-

•derivative conjugation: causative. The causative makes intransitive verbs transitive, and transitive verbs causative; it is marked by the affix -ā, e.g. sikhāiṇu ('to cause to learn' = 'to teach').

Syntax

Sindhi word order is usually Subject-Object-Verb but can be changed to put emphasis on a constituent. It is a head-final language: noun and verb modifiers precede their heads. Syntactical relations are indicated by the case system which employs the oblique case accompanied by postpositions for all functions except the subject which is marked by the nominative. The ablative and vocative cases have a marginal role. The postposition that marks the genitive is exceptional because it is declined like an adjective, agreeing with the possessed noun in number, gender and case.

Transitive verbs conjugated in any of the perfective tenses agree with their object while the subject adopts the oblique case, a phenomenon known as split ergativity. There are many compound verbs consisting of two or three verbs. The first verb is the main one and the other(s) modify some aspect of it.

Lexicon

Persian and Arabic, through Persian, have influenced greatly the Sindhi lexicon. English comes second, after them, as a source of loanwords.

Basic Vocabulary

Implosive sounds are represented by a double consonant.

one: hiku

two: bba

three: ṭī

four: cār

five: panja

six: cha

seven: sata

eight: aṭha

nine: nav

ten: ddaha

hundred: sau

father: pīu, piyu,

mother: māu

brother: bhāu, bhāī

sister: bherna

son: puṭu, puṭru

daughter: dhīa, dhīu

head: siru

eye: akhi

foot: peru, charanu

heart: dili, hio

tongue: jjibha

Key Literary Works

Shāh Jo Risālo (Shah's Message). Shah Abdul Latif (1689-1752)

It is a collection of mystical Sufi poetry, meant to be sung, composed by the shayk Shah Abdul Latif and compiled by his disciples. It is divided in 30 chapters or surs ("melodies"), each containing a number of poems, in local meters (like doha) or Persian ones, sharing the same theme. The Sufi saint incorporated fragments of folk romances in his poems focusing on several popular heroines whose quest for human love is paralleled with the yearning of the soul for divine love. In fact, the main subject of Latif is the evolution of the soul, marked by love and suffering, needed to attain mystical communion with God.

Sachal Jo Risālo (Sachal's Message). Sachal Sarmast (1739-1829)

Sachal was another Sufi mystic, who adopted the pen name “Sarmast” (the Intoxicated One) to stress ecstatic love as a means to approach God. He disdained formal religion attacking Hindu priests and Muslim religious scholars whom he considered hypocrites and ignorants.

Zeenat. Mirza Qalich Beg (1853-1929)

Published in 1890, it is the first succesful Sindhi novel. In spite of certain conventions and the idealization of the heroine, this work manages to give a realistic insight of Muslim life in Sindh at the time.

Poems. Shaykh Ayaz (1923-97)

Leader of the modernist poetry movement with a vast output coined in many forms (inspired in Indian, Persian and European models) and exploring varied themes.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Sindhi'. L. M. Khubchandani. In The Indo-Aryan Languages, 683-721. G. Cardona and D. Jain (eds). Routledge (2007).

-

-The Indo-Aryan Languages. C. P. Masica. Cambridge University Press (1991).

-

-Grammar of the Sindhi language. E. Trumpp. Trübner and Co./ F. A. Brockhaus (1872).

-

-Chronological Dictionary of Sind. M. H. Panhwar. Institute of Sindhology, University of Sind (1983).

-

-'At the Crossroads of Indic and Iranian Civilizations. Sindhi Literary Culture'. A. S. Asani. In Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, 612-646. S. Pollock (ed). University of California Press (2003).

Sindhi

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania