An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Niger-Congo, Volta-Congo, South Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Western Benue-Congo, Defoid, Yoruboid. Other languages of the Yoruboid group are Isekiri and Igala.

Overview. Yoruba is one of the major languages of Africa and one of the three principal ones of Nigeria together with Hausa and Igbo. It is spoken by one of the largest ethnic and cultural groups of Nigeria, the Yoruba, who seem to have migrated from the east to their present location west of the lower Niger River more than one-thousand years ago. They created several independent kingdoms ruled by hereditary kings, each centered around a capital city. One of them was the town of Ife which, besides its former political importance, still has a special religious significance as the site of the earth's creation according to Yoruba mythology. Many Yoruba were taken to the Americas as slaves and their beliefs and culture influenced the societies of Brazil, Cuba and other countries. Yoruba is a tonal language with very little inflectional morphology and a strict subject-verb-object word order.

Distribution. Yoruba is spoken mainly in southwestern Nigeria, particularly in the capital Lagos and in the states of Ekiti, Ogun, Ondo, Ọṣun, Ọyọ, Kwara and Kogi. Outside Nigeria, in southeastern Benin and in central and northern Togo.

Speakers. Around 29.4 million of which 28.5 live in Nigeria and the rest in Benin (800,000) and Togo (100,000).

Status. Yoruba is one of the four national languages of Nigeria, alongside Hausa, Igbo and English. It is used in the media and in the government of Yoruba-speaking states (Yorubaland). Many books, newspapers and magazines are printed in this language. It is used for primary education in Yorubaland and is studied in several Nigerian universities (English is usually used in secondary education). In Benin the language is called Nago and in Togo Ana. Since 1983 it is an official language of the National Assembly of Benin.

Varieties.

Yoruba has about twenty dialects plus a standard form that is close to the Ọyọ dialect. In some regions there is diglossia between Standard Yoruba, considered as a high variety, and the low variety dialects.

Oldest Documents

1819. A vocabulary compiled by Thomas Bowdich.

1828. Another vocabulary, this one compiled by Hannah Kilham.

1830-32. The teaching booklets of John Raban.

1843. The earliest Yoruba dictionary, published by Bishop Samuel Crowther, a former Yoruba slave settled in Sierra Leone.

1852. A Yoruba grammar written by Samuel Crowther.

1859-67. The first periodical in Yoruba and the earliest in a vernacular language of West Africa was published.

Phonology

Syllable structure: Yoruba syllables are open i.e. they all end in a vowel. The most frequent are those formed by a single vowel or by consonant plus vowel. Each syllable has a distinctive tone. Consonant clusters are not permitted but long vowels are possible.

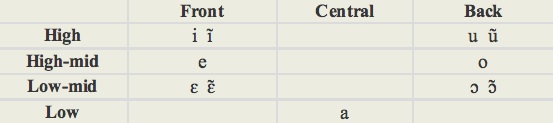

Vowels (11). The vowel system has seven oral and four nasalized vowels (marked with a tilde) though the nasal vowel [ɛ̃] occurs very infrequently. Nasalization is phonemic.

Vowel harmony. Yoruba has a limited vowel harmony: a high-mid vowel [e, o] cannot coexist with an low-mid vowel [ɛ, ɔ] in the same word.

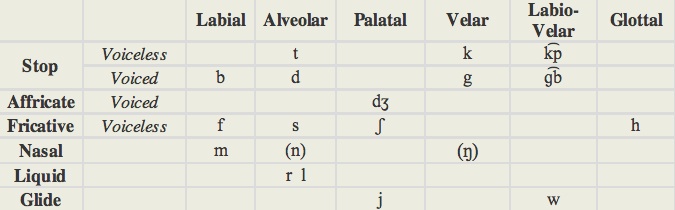

Consonants (17-19). The consonantal system is distinguished by its lack of p-sound and by the occurrence of two doubly articulated stops called labio-velars. Labio-velar consonants are very rare outside Africa but are found in some Nilo-Saharan languages and non-Bantu members of Niger-Congo. Besides, Yoruba has a syllabic nasal whose pronunciation depends on the following sound; if it is a vowel, the syllabic nasal is pronounced as a velar ŋ. When the following element is a consonant, the syllabic nasal is articulated at the same place (homorganic): before b it becomes m, before s is n and before k is pronounced ŋ.

Tones. Yoruba has three tones: high (marked by an acute accent), mid (unmarked or marked with a macron), and low (marked by a grave accent). The high tone cannot occur on a word initial vowel. When high tone follows a low tone, the high tone is realized as a rising tone. When a low tone follows a high tone the low tone is realized as a falling tone. Tones serve to distinguish lexical items and, sometimes, grammatical features.

Stress: is evenly distributed.

Script and Orthography.

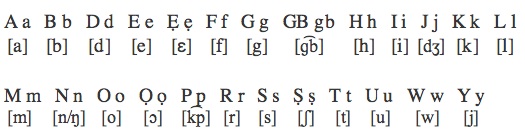

Yoruba is written in a form of the Latin alphabet comprised of 25 letters (below each of them its equivalent in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown):

-

•The mid-low vowels ɛ and ɔ are represented, respectively, by ẹ and ọ.

-

•When a nasalized vowel immediately follows an oral consonant it is represented by adding n after the vowel but if the nasalized vowel follows a nasal consonant it is not otherwise marked.

-

•The labio-velar k͡p is written p. The letter p is, otherwise, not required because the [p] sound doesn't exist in Yoruba.

-

•The labio-velar ɡ͡b is written gb.

-

•The affricate dʒ is represented by j.

-

•The fricative ʃ is represented by ṣ.

Morphology

-

a) Derivation

-

Yoruba word formation is for the most part derivational and not inflectional i.e. nouns and verbs are essentially invariant. Derivational processes involve affixation, reduplication (partial or complete) and compounding.

-

Affixation: Nominal forms can derive from verbs and verb phrases by means of affixes. Prefixes a- and ò- are used to form agent nouns i.e. denoting a person or an object that performs and action:

-

aṣẹ́: sieve (ṣẹ́ = to sieve)

-

apẹja: fisherman (pa = kill, ẹja = fish)

-

òjíṣẹ́: messenger (jẹ́ = answer, iṣẹ́ = message)

-

-

Prefixes ì- and à- are used to form abstract nouns from verbs and verb phrases:

-

ìṣẹ́: poverty (ṣẹ́ = to break)

-

àlọ: going (lọ = go)

-

The infix -kí- is usually inserted between a reduplicated word to form a new one:

-

ọmọkọ́mọ: a bad child (ọmọ + kí + ọmọ) ọmọ = child

-

Reduplication: partial or total may be used to express intensification, to form agentive nouns and adjectives from verbs and verbal phrases as well as ideophones:

-

1) intensive: púpọ̀ (much) →, púpọ̀púpọ̀ (very much)

-

2) adjective: jẹ (to eat) → jíjẹ (edible)

-

3) agentive noun: jà (fight) + ogun (war) → jagunjagun (warrior)

-

4) ideophone: ramúramù (a loud noise)

-

Compounding: two nouns may be joined by deleting the initial vowel of the second creating a new word with a different meaning:

-

ewé (leaf) + ọbẹ̀ (soup) = ewébẹ̀ (vegetable)

-

ìyá (mother) + ọkọ (husband) = ìyakọ (mother in law)

-

ẹran (meat) + oko (farm) = ẹranko (animal)

-

b) Nominal-Pronominal System

-

There is no grammatical gender, nouns are neither declined for case nor inflected for number, and there is no noun-class system. Plurals are indicated with a plural word or are marked by pronouns before the noun, or by demonstratives, or by reduplicated adjectives after the noun.

-

There are two classes of personal pronouns, strong and weak. The strong ones are invariant; they put emphasis on the person referred to and are also used for negation and in some focus constructions. Weak pronouns are used only with verbs and have different subject and object forms.

-

In negatives the 3rd. sg. subject pronoun is omitted. The form of the 3rd. sg. object pronoun is dependent on the verb that it follows i.e. it mimics the vowel of the verb:

-

ó fà á (‘he pulled it’)

-

ó ṣí í (‘he opened it’)

-

Possessive adjectives are rather similar to the object pronouns. Possessive pronouns are formed by adding the prefix ti- to the possessive adjective pronouns (tè- for the 1st sg):

Adjective

1s mi

2s rẹ/ẹ

3s rẹ̀

1p wa

2p yín

3p wọn

Pronoun

tèmi

tirẹ

tirẹ̀

tiwa

tiyín

tiwọn

-

There are two demonstrative pronouns: èyí (‘this’), and ìyẹn (‘that’) which are made plural by being prefixed with the 3rd plural personal pronoun àwọn. The interrogative pronouns are: tani (‘who?’) and kíni (‘what?’). The relative pronoun tí is invariable and requires pronominal recapitulation if the antecedent is a noun or pronoun.

-

c) Verbal System

-

Most Yoruba verbal stems are monosyllabic and are all invariable, not being conjugated for person, number or gender. They are always accompanied by the personal pronouns.

-

•tense-aspect: past, perfective, imperfective, future.

-

The bare stem of an action verb generally indicates a completed action in the past but that of stative verbs usually refers to the present. Tense and aspect are marked by particles that occur between the subject and the verb: progressive or imperfective ń, perfective ti, future á/ó/yió. The imperfective refers to an action in progress in the past or present, or to an habitual action. It can be combined with the perfective to indicate the beginning of an action in the past. Negation is done with the particle kò in main clauses and with má in prohibitions and subordinate clauses.

-

‣ Past

-

Olú ra aga

-

Olu buy chair

-

Olu bought a chair.

-

‣ Imperfective

-

wọ́n ń jó

-

They IMPF play

-

They are (were) playing.

-

‣ Perfective

-

ó ti lọ

-

He/she PF go

-

He/she has gone.

-

‣ Future

-

ọ̀rẹ́ mi á lọ

-

friend my FUT go

-

My friend will go.

-

‣ Progressive Perfect

-

mo ti ń gba lẹ́tà rẹ

-

I PF IMPF receive letter your

-

I have started to receive your letters.

-

•non-finite forms: infinitive or gerund are formed by the use of àti- and àì- prefixes, the first one for the affirmative and the latter for the negative sentences.

-

‣ Infinitive: àtirà = to buy

-

‣ Gerund: àtisùn = sleeping

-

‣ Negative gerund: àìdára = not being good

Syntax

Word order is Subject-Verb-Object which, due to the limited inflectional morphology, is quite strict. In the noun phrase the head appears in initial position: adjectives, demonstratives and relative clauses follow the head noun, the noun possessed precedes the possessor. Verb phrases and prepositional phrases are also head initial. If the verb has two objects, the second one is preceded by a preposition (ní) whithout meaning:

-

ó kọ wa ní Yoruba

-

He teach us prep. Yoruba

-

He taught us Yoruba.

When the verb is accompanied by a verbal complement, the latter follows the verb.

-

Táíwò rò pé ó sanra

-

Taiwo think that he/she fat

-

Taiwo thought that he/she was fat.

Adverbials also follow the verb.

Yes-no questions are formed by means of a particle at the beginning (ṣé/ǹjẹ́) or at the end of the sentence (bí). Content questions are posed by means of interrogative pronouns and adverbs.

Serial verb constructions, in which strings of verb phrases appear consecutively without any intervening conjunction or subordinator, are frequent. There is only one possible tense-aspect marker.

The second verb may indicate the direction of the action:

-

ó gbé e wá

-

he/she carry it come

-

He/she brought it.

The object of the first verb can be the subject of the second one:

-

ó tì mí ṣubú

-

he/she push me fall

-

He/she pushed me and I fell.

Two transitive verbs combined may have two object noun phrases:

-

ó pọn omi kún kete

-

he/she draw water fill pot

-

He/she drew water and filled the pot.

Otherwise, a single object for the two verbs may occur between them, indicating two successive actions by the same subject:

-

Ade ń ra ẹran jẹ

-

Ade IMPF buy meat eat

-

Ade is buying meat and eating it.

Focus constructions are commonplace. In them a word is put in focus by marking it with the morpheme ni and placing it at the front. The fronted constituent can be the subject or object of the verb, a complement of the verb or even the verb itself. If the subject is focused, a pronominal form must replace the fronted noun phrase in subject position. Similarly, when the emphasized element is the verb, a nominalized form of the verb appears in focus position and the verb itself continues to appear in its appropriate place inside the clause.

-

‣ No Focus:

-

Olú ra ìwé

-

Olu buy book

-

Olu bought a book.

-

‣ Object Focus:

-

Ìwé ni Olú rà

-

book FOC. Olu buy

-

It was a book that Olu bought.

-

‣ Subject Focus:

-

Olú ni ó ra ìwé

-

I FOC. 3sg. buy book

-

It is Olu that bought the book.

The pronoun ó is a reminder of the fronted subject pronoun but it doesn't indicate any specific person and number.

-

‣ Complement Focus:

-

Ní ilé ni ó ti bẹ̀rẹ̀

-

at house FOC. it PF start

-

It was in the house that it started.

-

‣ Verb Focus:

-

Rírà ni bàbá ra bàtà

-

buying FOC. father buy shoes

-

Father bought shoes.

-

rírà is a nominalized form of the verb ra.

Lexicon

Yoruba has borrowed many words from Hausa (some originally Arabic), Igbo and English. Like many other African languages, it has ideophones which are a special class of words with particular sound characteristics associated with vivid sensory or mental experiences. In Yoruba, ideophones are made by reduplication and consist of up to four repeated units. Relatives, old people and people in authority should be addressed with politeness which dictates the choice of pronouns, names and nicknames.

Basic Vocabulary

There are two sets of 1-10 numerals: a basic set (listed first) used for counting and a full set used as nouns or adjectives (listed second). The numerals of the basic set have low-tone initials; in the full set an initial m is added and the low-tone changes to a high-tone (except for 1 which drops the first vowel).

one: ọ̀kan (ení); kan

two: èjì; méjì

three: ẹ̀ta, mẹ́ta

four: ẹ̀rin, mẹ́rin

five: àrún, márún

six: ẹ̀fà, mẹ́fà

seven: èje, méje

eight: ẹ̀jọ, mẹ́jọ̀

nine: ẹ̀sán, mẹ́sán

ten: ẹ̀wá, mẹ́wá

hundred: ọgọ́rùn

father: bàbá

mother: ìyá

older brother: ẹgbon ọkunrìn

younger brother: àbúró ọkunrìn

older sister: ẹgbon obìnrin

younger sister: àbúrò obìnrin

son: omokùnrin

daughter: ọmọ obìnrin

head: orí

eye: ojú

hand: ọwó

foot/leg: ẹsẹ̀

heart: ọkàn

tongue: ahon, èdè

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

-

Further Reading

-

-'Yoruba'. D. Pulleyblank & O. O. Orie. In The World's Major Languages, 866-882. B. Comrie (ed). Routledge (2009).

-

-A Grammar of Yoruba. A. Bamgboṣe. Cambridge University Press (1966).

-

-Teach Yourself Yoruba. E. C. Rowlands. English Universities Press (1969).

-

-Verbal Categories in Niger-Congo. Chapter 21: Yoruba. J. Hewson. Memorial University, Department of Linguistics. http://www.mun.ca/linguistics/nico/index.php

Yoruba

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania