An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Name: Bangla, term which tends to replace the established name.

Classification: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Modern Indo-Aryan, Eastern. It is closely related to Assamese.

Overview. Bengali is, after Hindi, the second largest language of South Asia, and the sixth largest of the world. It emerged from Middle Indo-Aryan at the beginning of the second millennium CE in Bengal, in the northeast of India. A number of phonological and morphological changes relates Bengali to other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages like Assamese and Oriya. Due to the early and widespread Islamization of the area many words from Arabic and Persian were incorporated into Bengali. In 1947 the linguistic area of Bengal was split along religious lines: West Bengal with a Hindu majority remained in India while a new state was created with Muslim majority (Eastern Pakistan, that later became Bangladesh).

Distribution and Speakers. There are about 265 million Bengali native speakers of which 168 million in Bangladesh (98 % of the total population) and 97 million in India, mainly in the states of West Bengal, Assam, Tripura, Jharkhand, Bihar and Orissa:

West Bengal

Assam

Jharkhand

Tripura

Orissa

Bihar

Others

79,300,000

8,500,000

3,000,000

2,500,000

570,000

514,000

2,300,000

Status. Bengali is the official language of Bangladesh as well as the official language of West Bengal. It is recognized in the Indian Constitution as one of the 23 official languages of the country.

Varieties. More important than any dialect is the phenomenon of diglossia or the coexistence of two styles of the language: sadhu bhasa, formal and literary, and colloquial calit bhasa. The first uses more Sanskrit loanwords and its morphology is more conservative.

Standard Colloquial Bengali is based on the language spoken in Kolkata, the capital of West Bengal. The regional dialects can be divided into Northern, Western, Southern and Eastern groups. Among the Eastern dialects, it is worth mentioning Dhaka, spoken in the capital of Bangladesh, and Chittagong, spoken in the second city of this country located close to Burma and influenced by Tibeto-Burman languages.

Oldest Document. It is the Caryāpada, a collection of 47 Buddhist hymns written by 23 poets between 1000-1200.

Phonology

Vowels (14). All oral vowels have nasal counterparts and nasalization is phonemic (it is indicated with a tilde above the vowel). In Bengali, like in the other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages (Oriya, Assamese), short and long vowels, typical of Indo-Aryan, have coalesced and their distinction is no longer phonemic. Most words end in a vowel.

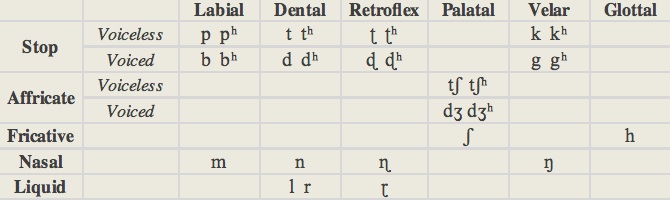

Consonants (29). Bengali has 29 consonants in total, including 20 stops, 2 fricatives, 4 nasals, and 3 liquids. The stops are articulated at five different places, being classified as labial, dental, retroflex, palatal and velar. The palatal stops are, in fact, affricates. Every series of stops includes voiceless and voiced consonants, unaspirated and aspirated, this four-way contrast being unique to Indo-Aryan among Indo-European languages (Proto-Indoeuropean had a three-way contrast only).

-

•In Bengali, like in Oriya and Assamese, the three sibilants of Sanskrit have coalesced into one fricative (ʃ in Bengali, s in Oriya, x in Assamese). In Bengali the palatal sibilant ʃ, in some environments (before t, tʰ, n, r, l), is realized as dental s.

-

•The retroflex consonants of Bengali, articulated immediately behind the alveolar crest, are not from Indo-European origin. They are, probably, the result of Dravidian language influence. Bengali has a retroflex liquid not inherited from Sanskrit.

-

•There is great variability in the pronunciation of glides (semivowels) in different dialects and among different speakers. Most often they are not pronounced at all and they are not considered as true phonemes in Bengali.

Script and Orthography

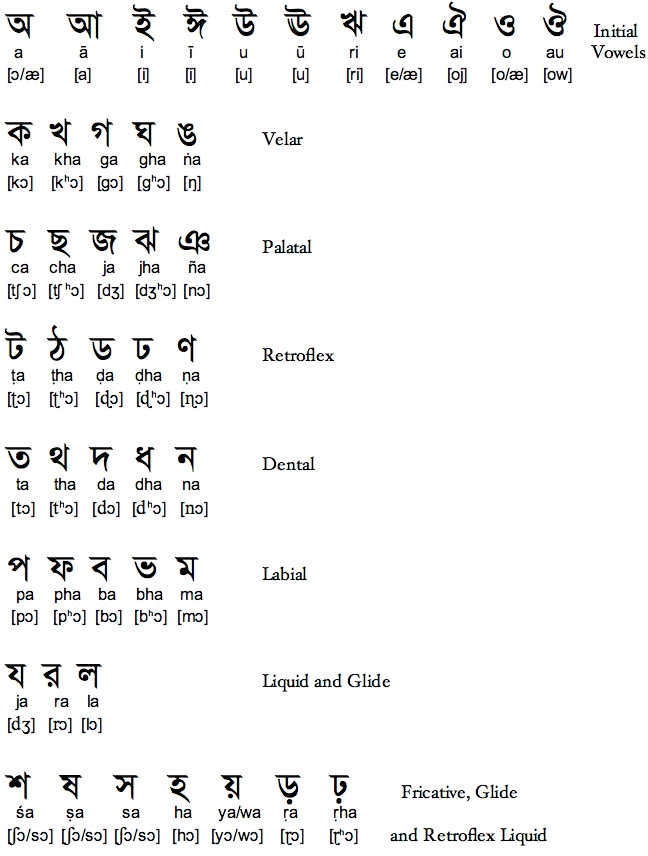

Bengali uses its own script, a descendant of Brāhmī, which is also used, with minor modifications, for Assamese. The Bengali script, that has 46 letters, is an abugida alphabet in which every consonant carries the inherent vowel [ɔ]. Its principles are similar to those of Devanāgarī script (see Hindi). As the script doesn’t reflect accurately the pronunciation of vowels we have used here (as in most grammars) a phonetic transcription for them.

-

•the Bengali script has signs for short and long vowels (ā, ī, ū) but in informal speech they are all pronounced short. The vowel [æ] can be rendered as e, a, o.

-

•the syllabic vowel ri is present only in Sanskrit loanwords.

-

•the aspirated stops and affricates are rendered as digraphs (pʰ = ph, dʰ = dh, etc).

-

•the retroflex stops [ʈ], [ɖ] are transliterated ṭ , ḍ.

-

•the affricates [tʃ], [dʒ] are transliterated c , j.

-

•the Bengali script has three signs for sibilants (ś, ṣ, s) but they are all pronounced [ʃ] (or in some contexts [s]).

-

•the nasals [ɳ], [ŋ] are represented by ṇ, ṅ. There is a sign for the nasal palatal (ñ) in the script but it is pronounced as n.

-

•the retroflex liquid [ɽ] is transliterated ṛ/ṛh.

Morphology

-

Nominal. Attributive adjectives are invariable, they are not inflected for case, gender or number. Nouns may be marked for plural, definiteness and case by adding the appropriate suffixes (in that order).

-

•gender: Bengali, like other Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, has no grammatical gender but distinguishes sex.

-

•number: singular and plural. Animate and definite inanimate nouns, as well as pronouns, have plural forms. Only countable inanimate nouns may be pluralized; uncountable nouns are not usually marked for plural. There are two plural suffixes:

-

-(e)ra is for animate nouns only, definite or indefinite

-

-gulo/-guli/-gula is for animate and definite inanimates

-

chele ('boy') → chelera ('boys/the boys') → chelegulo ('boys/the boys')

-

juto ('shoe') → jutogulo ('the shoes')

-

•definiteness: nouns can be marked as definite by incorporating the suffix -ṭa/-ṭi e.g. cheleṭi ('the boy'). A noun is also definite when preceded by a possessive adjective or a demonstrative.

-

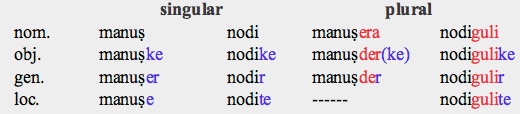

•case: nominative, objective, genitive, locative.

-

The objective is used to mark direct or indirect objects. The locative indicates place, time, instrument, origin or cause (it is a conflation of the Sanskrit instrumental, ablative and locative cases). Below, we show the declension of manuṣ ('man') and nodi ('river'):

-

black: nominal base

-

blue: declension suffix

-

red: plural suffix

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, relative, indefinite.

-

Personal pronouns are genderless but distinguish between human and non-human as well as several degrees of status (three in the second person, two in the third person).

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish three deictic degrees: proximate ei/e, distal oi/o and invisible śei/śe.

-

The interrogative pronouns are ke (‘who?’) and ki (‘what?’). Other interrogatives are kothae (‘where?’), kæmon (‘how?’), kon (‘which?’), kæno (‘why?’), kɔto (‘how much?, how many?’).

-

The relative pronoun is ja.

-

Verbal. Verbal roots are mono- or disyllabic; many of them are derived from nouns by adding the suffix -a. Markers for aspect/tense follow the stem and precede the personal inflections.

-

•person and number: number is not marked but several forms exist for different status: 1st, 2nd despective, 2nd ordinary, 2nd honorific, 3rd ordinary, 3rd honorific. Ambiguities are avoided by using the personal pronouns.

-

•aspect: imperfective, perfective, perfect.

-

•tense: present, present continuous, future, simple past, past habitual-past conditional, past continuous, present perfect, past perfect.

-

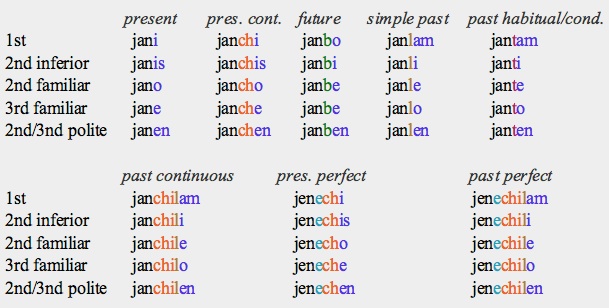

The present is formed by attaching the personal endings directly to the simple stem of the verb (the verbal noun minus -a).

-

Another four tenses are formed by adding one tense/aspect marker to the stem: (c)ch for the present continuous, b for the future, l for the simple past, t for the past habitual-past conditional. Three tenses are formed by a combination of two or more tense-aspect markers: the past continuous is marked by (c)ch + l, the present perfect by e (a completive marker) + ch, and the past perfect by e + ch + l.

-

There are four different sets of personal endings. One is used for the simple present and (c)ch-stems, a second one for b-stems, the third one for t-stems and l-stems, and the fourth one for the imperative.

-

For example, the conjugation of jan- (‘know’) is as follows:

-

black: simple stem, orange: progressive marker, green: future marker, brown: past marker,

-

red: habitual-counterfactual marker, light blue: completive marker, blue: personal markers.

-

The translation of the 1st person of these tenses is:

-

-

present: 'I know'/'we know'

-

present continuous: 'I am knowing'/'we are knowing'

-

future: 'I will know'/' we will know'

-

simple past: 'I knew'/'we knew'

-

past habitual/conditional: 'I used to know'/ '(if) I had known'/'we used to know'/ '(if) we had

-

known'

-

past continuous: 'I was knowing'/'we were knowing'

-

present perfect: 'I have known'/'we have known'

-

past perfect: 'I had known'/'we had known'

-

•mood: indicative, imperative.

-

The imperative has a present and a future tense. The present imperative like the present indicative lacks any tense marker. Its 2nd person familiar form is identical to that of the indicative but other forms have different personal endings. The future imperative is formally identical to the future indicative in the 3rd familiar and 2nd/3rd polite but the second familiar form lacks the b infix and has a distinctive personal ending. Negative commands are expressed with the future imperative (never with the present imperative).

-

•voice: active, passive. The passive voice in Bengali is frequently impersonal (i.e. it lacks a subject). It is formed with the verbal noun plus the verb ho- (‘become’) or ja- (‘go’).

-

•derivative conjugation: causative. The causative is usually formed by adding -a to the monosyllabic verb stem.

-

•non-finite forms: verbal noun, infinitive, past active and conditional participles.

-

The infinitive adds -te to the stem e.g. jante ('to know'). The verbal noun is formed by suffixing -a (or -oa after vowel) to monosyllabic stems and -no to dysyllabic stems:

-

jan → jana (‘knowing’)

-

jana → janano (‘informing’)

-

ga → gaoa (‘singing’)

-

The past participle expresses an action which precedes another one; combined with another verb it forms a compound verb that can have an entirely different meaning; it is made by suffixing -e to the stem e.g. jene (‘having known’).

-

The conditional participle has temporal and conditional connotations; it is formed by suffixing -le to the stem e.g. ami janle (‘if I know’).

Syntax

Bengali word order is a rather strict Subject-Object-Verb, due to its relatively poor case system. Normally, first in a sentence comes the subject noun phrase, followed by the indirect object; next comes the direct object followed, eventually, by an oblique object noun phrase (frequently introduced by a postposition). Nominal modifiers precede their heads and verbal modifiers follow the verb.

Bengali has several postpositions, derived from nouns or from participles, which govern nouns declined in one of two cases, the nominative or the genitive. Generally subjects are marked in the nominative case or are unmarked. The finite verbs normally agree with their subjects in person, except in passive constructions, where the verb is in the form of a verbal noun and the subject is marked with the genitive case or it is omitted, and in indirect subject constructions with subjects in the genitive case. The copula is not usually expressed in the affirmative present tense.

A conditional sense may be expressed in Modern Bengali:

a) by using the particle jodi (similar to the Sanskrit particle yadi), meaning ‘if/when’, with a finite clause.

-

b) without a conditional particle, using the conditional participle.

Negation is expressed with the particle na following the verb, in independent clauses. In subordinate clauses, finite and non-finite, this particle precedes the verb.

Relative clauses generally precede main clauses. Impersonal phrases are common; they express possession, possibility, obligation, physical sensations, feelings, and experiences.

Lexicon

Most Bengali words descend from Old Indo-Aryan (Sanskrit and putative related languages), having experienced the appropriate sound changes. However, a number of Bengali words which are identical, or very similar, to their Sanskrit counterparts are considered borrowings promoted by the prestige of the mother language. Bengali has also several thousand words from Arabo-Persian origin due to Muslim influence. English is another important source of borrowings.

Basic Vocabulary

one: æk

two: dui, du

three: tin

four: car

five: pãc

six: chɔy

seven: sat

eight: aṭ

nine: nɔy

ten: dɔś

hundred: śo

father: baba

mother: ma

older brother: dada

brother: bhai

sister: bon

son/boy: chele

daughter/girl: mee

head: śīrṣa

face: mukh

eye: akṣi

hand/arm: hat

foot: pa

heart: hṛdɔy

tongue: jihba

Key Literary Works (forthcoming).

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-Bengali. H-R. Thompson. London Oriental and African Language Library 18. John Benjamins (1992).

-

-'Bengali'. M. H. Klaiman. In The World's Major Languages. B. Comrie (ed), 417-436. Routledge (2009).

-

-Bengali Language Handbook. P. S. Ray, M. A. Hai & L. Ray. Center for Applied Linguistics (1966).

-

-An Advanced Course in Bengali. E. Bender & T. Riccardi. South Asia Regional Studies (1978).

-

-The Origin and Development of the Bengali Language (3 vols). S. K. Chatterji. Allen and Unwin, London (1926).

Bengali

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania