An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Celtic, Insular Celtic, P-Celtic, Brythonic.

According to one hypothesis, Celtic languages are divided into P-Celtic and Q-Celtic. P-Celtic links the Brythonic insular languages (Welsh, Cornish, Breton) with continental Gaulish. Q-Celtic links the Goidelic insular languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx) with continental Hispano-Celtic. In P-languages the Proto-Celtic labiovelar *kʷ became p; in Q-languages it became k.

Overview. Breton was taken from southern England to northwestern France, between the 4th and 8th centuries CE, by Celtic refugees displaced by the influx of Anglo-Saxons. Breton is closely related to Cornish and Welsh but has received the influence of French and possibly of a continental Celtic language spoken in the region.

Distribution and Speakers. It is spoken in Brittany (northwestern France), in the departments of Finistère, Morbihan and Côtes d'Armor. The 2001 French census shows that there are about 270,000 speakers of Breton.

Status. Breton is an endangered language and the number of its speakers is diminishing. Very few children are learning Breton at home or at school. Publishing in Breton is encouraged but this has not stopped the language's decline.

Varieties. There are four dialects divided into two groups and belonging to four dioceses:

-

A)

-

1) Dialect of Léon in the northwest (Leoneg or Léonais).

-

2) Dialect of Tréguier in the northeast (Tregerieg or Trégorrois).

-

3) Dialect of Cornouaille in the southwest (Kerneveg or Cornouaillais)

-

B)

-

4) Dialect of Vannes in the southeast (Gwenedeg or Vannetais), which is the more divergent.

Oldest Documents. Remnants of Old Breton, dating from 9th-11th centuries, are in the form of some two-thousand personal and place names found mainly in charters, and one-thousand glosses in Latin texts (most of them just one or two-word long though there are also a few sentences). The two main manuscripts containing Old Breton material are the early 9th-century Priscian’s Latin Grammar and Angers MS 477, a collection of scientific works from 897 CE.

Periods

Old Breton, from 9th to 11th centuries, represented by personal and place names plus isolated words scattered in Latin texts.

Middle Breton, from 11th century to circa 1650, strongly influenced by French. A Breton-French-Latin dictionary, the Catholicon by Jehan Lagadeuc, appeared in 1499.

Modern Breton: from circa 1650 until present. Its beginning is marked by Julien Maunoir’s Le Sacré Collège de Jésus (1659) accompanied by a grammar and a dictionary which reflect a number of changes in orthography.

Phonology

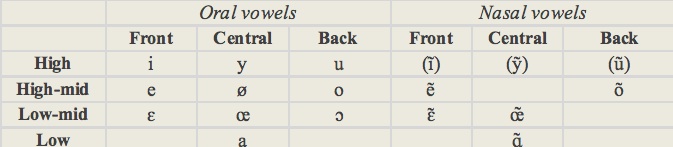

Vowels (15-18). Breton has short and long vowels, oral and nasal. Unstressed vowels are short. Stressed vowels are short before a voiceless sound or a geminate consonant; otherwise they are long.

It also has diphthongs which include a vowel plus a glide, that can be [w], [ɥ], [j].

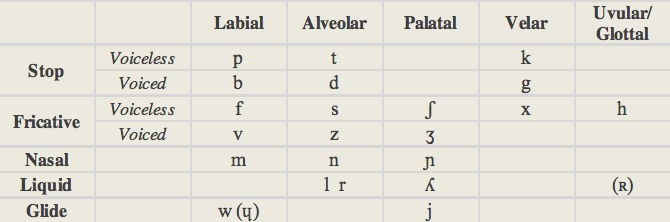

Consonants (22). Word-initial consonants, voiceless consonants and [m] are fortis (strongly articulated). Voiced fricatives are lenis (weakly articulated). Voiced stops and [l], [n], [r] can be fortis or lenis.

All voiceless consonants are voiced before a vowel or l, m, n, r. Final voiced consonants are devoiced, except when the next word begins with a vowel.

-

ɥ is a front-rounded glide (a variant of w) that occurs before or after vowels.

Initial consonant mutation. Like other Celtic languages, Breton has initial consonant mutations triggered by grammatical markings and the presence of various particles. There are four types of initial consonant mutation:

a) Lenition (soft mutation). The initial consonant of singular feminine nouns or masculine human plurals (and also the following adjective) are lenited after the indefinite or definite article. Voiceless stops become voiced, voiced stops become fricatives, m becomes v (when required, the symbols of the International Phonetic Association are shown between brackets):

p→b; t→d; k→g; b→v; d→z; g→c'h [x]; gw→w; m→v

For example:

*kelaouenn (magazine) → ar gelaouenn (the magazine); feminine singular

*kelennerien (teachers) → ar gelennerien (the teachers); masculine human plural

*toenn (roof) → an doenn (the roof); feminine singular

*mamm (mother) + mad (good) → ar vamm vad (the good mother); feminine singular

b) Spirantization. Voiceless stops become fricatives when a noun is preceded by some possessive or direct object pronouns as well as before the numerals three, four and nine.

p→f; t→z; k→c'h [x]

For example:

*penn (head) → va fenn (my head)

*tad (father) → he zad (her father)

*kalon (heart) → tri c'halon (three hearts)

c) Provection (strong mutation). Voiced stops become devoiced when a noun is preceded by a 2nd person possessive or object pronoun:

b→p; d→t; g→k; gw→kw

For example:

*dent (teeth) → ho tent (your teeth)

*goulenn (question) → ho koulenn (your question)

d) Mixed mutation (lenition + provection): is caused by the verbal particle e, the present participle particle o, and the conjunction ma (‘if’).

b→v; d→t; g→c'h [x]; gw→w; m→v

For example:

*goulenn (to ask) → ma c'houlenn (if … asks)

*gwelet (to see) → o welet (seeing)

Stress: in most dialects, stress usually falls on the penultimate syllable and is based on intensity but in Gwenedeg there is a pitch accent that affects the last syllable.

Script and Orthography

The Breton script is based on the Roman alphabet. A unified orthography called Peurunvan ('totally unified') or zedacheg (for digraph zh) or KLTGw (the initial of the four dialects), was created in 1941. In 1954 a new spelling called Orthographie Universitaire was created, and in 1970 a third orthography, etrerannyezhel (‘interdialectal’), was produced to take into account all regional differences. However, Peurunvan is the most popular and is the one presented here. Below each letter its equivalence in the International Phonetic Alphabet is shown between brackets:

-

•The remaining three oral vowels are represented by digraphs: [ø] and [œ] by eu; [u] by ou

-

•The nasal vowels are represented by digraphs or trigraphs having ñ as its last element: [ĩ] = iñ; [ɛ̃/ẽ] = eñ; [ỹ] = uñ; [œ̃] = euñ; [ɑ̃] = añ; [ũ] = ouñ; [õ] = oñ

-

•Some consonants are also represented by digraphs, namely: [ɲ] by gn; [ʎ] by lh

-

•[w] is written w or ou, occasionally v.

Morphology

-

Nominal

-

•gender: masculine, feminine.

-

•number: singular, plural. There is also a singulative marker (-enn) to single out one item of a collective noun. For example, logod means 'mice' but logodenn means a single mouse. The singulatives are feminine.

-

There is a dual referring to parts of the body that come in pairs; it counts as plural for verbal agreement. It is formed by prefixing the numeral two (masculine daou-, feminine div-) to the noun: lagad (eye) → daoulagad (eyes), askell (wing) → divaskell (wings).

-

The plural is formed:

-

1) by adding a suffix to the singular (-où, -ez, -ien, -ed, etc):

-

poan (pain)→ poanioù (pains)

-

ti (house) → tiez (houses)

-

loen (animal) → loened (animals)

-

2) by an internal change:

-

elerc'h (swan) → alarc'h (swans)

-

maen (stone) → mein (stones)

-

3) by an internal change plus a suffix:

-

bag (boat) → bigi (boats)

-

roc'h (rock) → reier (rocks).

-

4) by using a suppletive word: den (person) → tud (people).

-

•possession: the possessor follows the possessed object. There are several possible constructions:

-

1) possessed + article/quantifier/possesive pronoun + possessor (the possessed noun loses the article):

-

the girl's hat: tog ar verc'h

-

possessed-article-possessor

-

hat the girl

-

my mother's book: levr ma mamm

-

possessed-possessive-possessor

-

book my mother

-

2) formation of a compound noun:

-

cartwheel: rod (wheel) + karr (cart) → rodkarr

-

3) by the preposition da before the possessor:

-

a daughter of Yann: ur verc'h da Yann

-

•articles: Breton has an indefinite article used with singular nouns and a definite article. Articles are not inflected for gender or number. The indefinite article has several forms: un, ul, ur . The definite article is also polymorphic: an, al, ar. These different forms are induced by the consonant or vowel that follows: un and an before vowels, n, d, t, h; ul and al before l; ur and ar in other cases.

-

•adjectives: are not inflected for gender and number and almost always follow the noun they modify. They form diminutives, comparatives and superlatives adding suffixes to the base. For example, from the base bras (‘big’) derive the following forms:

-

bras → brazik (diminutive)

-

bras → brasoc'h (comparative)

-

bras → brasañ (superlative)

-

•adverbs: the majority of adverbs are compounds formed with a preposition plus a noun, adjective or verb. Adjectives without modification are sometimes used as adverbs.

-

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative, indefinite.

-

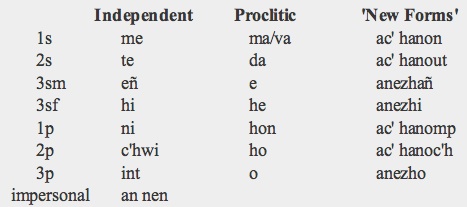

Personal pronouns distinguish three persons and two numbers as well as gender in the 3rd, singular.

-

They have independent, proclitic, and 'new' forms.

-

-Independent or 'strong' forms serve to emphasize the subject but sometimes are also used as object pronouns.

-

-Proclitic forms function as object pronouns or possessive adjectives.

-

-The 'new forms' are object pronouns that are able to replace the proclitic forms except at the beginning of a clause.

-

Possessive pronouns are formed by placing proclitic pronouns before the determinatives hini (sg.) and re (pl.): ma hini (‘mine’), ho re (‘yours’), etc.

-

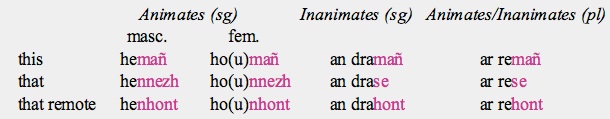

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish three deictic degrees and are related to the following adverbs: amañ (‘here’), aze (‘there’), ahont (‘there, further away’). They have different forms for animate and inanimate nouns.

-

Interrogative pronouns generally come first in the sentence. They are: piv (‘who?’), petra (‘what?’), and pehini (‘which?’); the latter has a plural form (‘pere’). Interrogative adverbs are: pelec'h (‘where?’), penaos (‘how?’), perak (‘why?’), pegoulz/pevar/peur (‘when?’).

-

Indefinite pronouns: all (‘other’), nebeud (‘a little, a few’), meur (‘several’), etc.

-

Verbal. There are two verbal particles: a after the subject and direct object, and e after the indirect object. Breton has few irregular verbs.

-

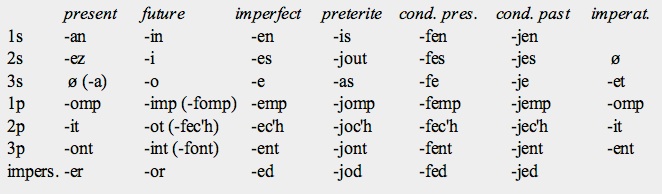

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p. There is also an impersonal or general form.

-

•aspect: perfective, imperfective (progressive, habitual). The perfective expresses a completed action and the imperfective an habitual or ongoing action.

-

•mood: indicative, imperative, subjunctive (rare).

-

•voice: active and passive.

-

•tense: present, future, imperfect, preterite (restricted to the written language), conditional present (or potential) and conditional past (or hypothetical). Besides, Breton has several compound tenses.

-

The simple tenses are formed by adding a specific set of personal endings to the stem of the verbal noun. The personal endings are:

-

For example, the conjugation of the regular verb lenn (‘to read’) is as follows:

-

There are few irregular verbs, including mont (‘to go’), ober (‘to do’), dont (‘to come’). These verbs have a radical which is different from the verbal noun but the personal endings are the same as in the regular verbs. Their present tense is shown in the table.

-

The verbs bezañ (‘to be’) and kaout (‘to have’) are very complex; they have two verbal nouns each: bezañ/bout and kaout/endevout. Bezañ has numerous forms in the present and imperfect expressing habit, identification, time or place. Kaout has neutral and habitual forms in the present and imperfect.

-

Compound tenses are formed with the past participle and the conjugated forms of the verbs kaout or bezañ as auxiliaries. The use of the present tense of the auxiliary verb gives the meaning of something done today or habitually (‘he has done’). The past tense of the auxiliary gives the sense of remoteness of the action (‘he had done’), etc.

-

Preverbs are prefixes that change the verb's meaning. For example, de- gives the sense of "towards the speaker": kas (‘to take’), degas (‘to bring’). Di- gives the opposite meaning: kreskiñ (‘to grow’), digreskiñ (‘to diminish’).

-

•non-finite forms: verbal noun, present participle, past participle, gerund.

-

The verbal noun: may be identical with the root, but sometimes it carries a suffix (-añ is the commonest; others are -iñ, -et, -at, etc).

-

komz → komz (‘to come’)

-

lenn → lenn (‘to read’)

-

kemer → kemer (‘to take’)

-

skriv → skrivañ (‘to write’)

-

debr → debriñ (‘to eat’)

-

berv → birviñ (‘to boil’), with vowel change

-

sell → sellet (‘to look’)

-

labour → labourat (‘to work’)

-

The present participle and gerund are formed with the verbal noun plus a preceding particle (o for present participle, ur for gerunds).

-

The past participle is formed by adding -et to the verbal root.

Syntax

Basic word order is Verb-Subject-Object and is relatively free. The verb to have (kaout) is the only Breton verb that agrees fully with its subject, the others, if the subject is independently expressed, don’t agree with it. Adjectives follow the noun they modify; they can also be used as adverbs without any change. Adverbs can be found in the core of the verb phrase or outside it. The adverbs of place come first, followed by those of time.

Emphasis on a certain element of the sentence may be achieved by placing it in initial position or by the use of the emphatic particle 'ni following the word or phrase to be emphasized. The subject can be highlighted by suffixing the corresponding personal pronoun.

Interrogative sentences can be formed with the particle ha or interrogative pronouns and adverbs, all placed in initial position.

Negation is expressed by the particle ne used after the subject, direct and indirect object, adverbs and as a negator introducing nominal clauses.

Coordinated clauses are linked by coordinating conjunctions like ha (‘and/if/wether’), pe (‘or’), etc. Subordinate clauses may be introduced by compound conjunctions such as perak e (‘why’), dre ma (‘because’), ken ma/na (‘until’), hep ma/na (‘without’), etc. To link finite verbal forms the particles ma and e are used. Relative clauses are marked by the use of the particles a, ma or na.

Lexicon

Breton’s vocabulary is essentially Celtic with many borrowings from Latin, French and English.

Basic Vocabulary

one: unan

two: daou (m), div (f)

three: tri (m), teir (f)

four: pevar (m), peder (f)

five: pemp

six: c'hwec'h

seven: seizh

eight: eizh

nine: nav

ten: dek

hundred: kant

father: tad

mother: vamm

brother: breur

sister: c'hoar

son: mab

daughter: verc'h (merc'h)

head: penn

eye: lagad

foot: troad

heart: kalon

tongue: teod

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Breton'. I. Press. In The Celtic languages, 427-487. M. J. Ball & N. Müller (eds). Routledge (2009).

-

-Histoire de la Langue Bretonne. H. Ablain. Gisserot (1995).

-

-A Handbook of Modern Spoken Breton. M. McKenna. Niemeyer (1998).

-

-Celtic Culture. A Historical Encyclopedia (5 vols). J. T. Koch (ed). ABC-CLIO (2006).

Breton

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania