An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Alternative Name: Irish Gaelic.

Classification: Indo-European, Celtic, Insular Celtic, Q-Celtic, Goidelic.

According to one hypothesis, Celtic languages are divided into P-Celtic and Q-Celtic. P-Celtic links the Brythonic insular languages (Welsh, Cornish, Breton) with continental Gaulish. Q-Celtic links the Goidelic insular languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx) with continental Hispano-Celtic. In P-languages the Proto-Celtic labiovelar *kʷ became p; in Q-languages it became k.

Overview. Irish is a Goidelic Celtic language spoken from the 5th century onwards in Ireland, Scotland and south-west Wales. The two other Goidelic languages, Scottish Gaelic and Manx, arose from Irish colonizations in Britain and in the isle of Manx in the early historic period, progressively replacing Irish in those areas. There were also Irish-speaking colonies in Wales, but little of their language has survived.

Like all Celtic languages, Irish has been declining for a long time but recently the tendency has been reversed. Along with Welsh, that belongs to a separate branch, it is the most important Celtic language not only by the relative abundance of its speakers but also by its antiquity and by the richness of its literature.

Distribution and Speakers. Irish is spoken mainly in Ireland and British Northern Ireland (Fermanagh and Armagh counties, Belfast) as well as by some expatriates in Canada and U.S.A. According to the 2006 census, there are 540,000 Irish speakers in Ireland. A further 95,000 live in U.K. (2004 census), 25,000 in U.S.A and 7,000 in Canada.

Status. Irish is one of the national languages of the Republic of Ireland, and it is also an official E.U. language. It is taught in public schools and is required for certain civil-service posts. All official documents of the Irish Government must be published in both Irish and English or Irish alone. All Irish speakers are bilingual in English.

Varieties. Besides Standard Irish, which is taught in most schools in Ireland, there are several regional dialects: Munster Irish (spoken in County Kerry, Ring, County Waterford, Muskerry, Cape Clear Island, County Cork), Connacht Irish (in Connemara and the Aran Islands), and Ulster Irish (in the three counties of Ulster).

Oldest Documents

5th c. CE. Ogham stone inscriptions written in sets of strokes or notches.

early 8th c. CE. Brief passages in Old Irish preserved in the Book of Armagh, a Latin manuscript about the life of St. Patrick. They are among the earliest surviving continuous prose narratives in the language.

early 8th c. CE. The Cambrai Homily is the earliest known Irish homily.

750-850 CE. Three collections of Old Irish glosses found in grammars and Latin Bibles.

Periods

Primitive Irish (300–500 CE) preserved in Ogham inscriptions on stone.

Old Irish (600–900 CE ) preserved in the Latin alphabet in several medieval manuscripts.

Middle Irish (900–1200 CE). Distinguished by a substantial simplification of morphology.

Modern Irish (1200 CE-present). Divided into Early Modern (1200-1600) when a highly standardized literary norm was dominant, and Late Modern (1600 to the present) when Scottish Gaelic and Manx emerged, and the modern Irish dialects appeared in writing.

Phonology

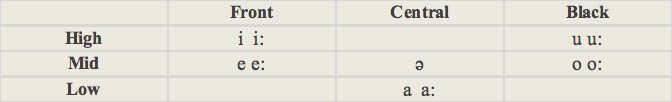

Vowels. Irish has 11 simple vowels and 4 diphthongs. In Irish spelling, sequences of two or three vowels representing only one sound are common. One of them is actually pronounced while the others indicate the quality of neighboring consonants (see below).

-

a) Monophthongs (11):

-

b) Diphthongs (4): iə, uə, ai, au

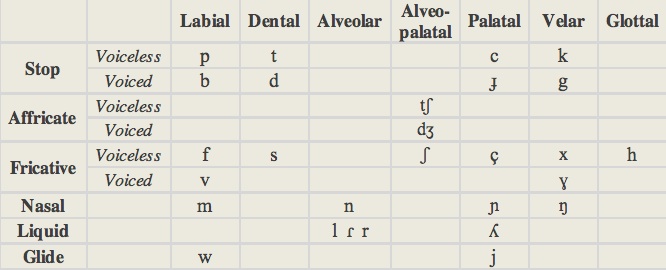

Consonants. All Irish consonants (except h) have two sets of contrasting sounds: 'broad' and 'slender'. Broad consonants are velarized sounds which are distinguished in writing by being preceded or followed by the vowels i or e. Slender consonants are palatalized sounds which are distinguished in writing by being preceded or followed by the vowels a, o, or u. In consonant sequences, all of them agree in quality, being either all slender or all broad. The liquid consonants include two laterals, (one alveolar, one palatal) and two r-sounds (one trill and one flap).

Initial consonant mutation. In Irish, like in all Celtic languages, a phonetic process known as initial consonant mutation is widespread. It is triggered by grammatical markings and the presence of various particles.

-

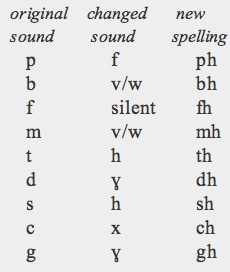

•The most frequent type is lenition in which some initial consonants of a word change into a fricative. It occurs to indicate the gender of nouns, to mark tense or negative verbs, following some particles, etc. Only nine consonants can be lenited: p, b, f, m, t, d, s, c, g. In spelling, the change in pronunciation is marked by adding h after the affected consonant:

-

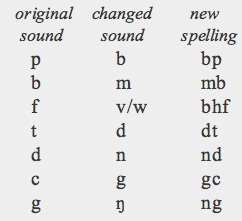

•Eclipsis affects a particular set of seven initial consonants. It is caused by preverbal particles, plural possessives, the numbers 7-10, etc. It is indicated in spelling by adding the changed sound before the original one:

-

•H-prefixation: unstressed particles ending in a vowel followed by a word beginning with a vowel cause the prefixation of it by an h sound that is reflected in spelling.

Stress: words tend to be stressed on the first syllable.

Script and Orthography

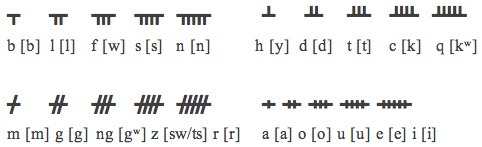

Until the 5th century CE, Irish was written in the Ogham script, an alphabet invented for inscribing Irish and Pictish on stone monuments. In its simplest form, Ogham consists of four sets of strokes, or notches, each set containing five letters.

After the 5th century CE the Latin alphabet began to be used to write Irish. The Modern Irish alphabet has just eighteen letters (equivalences in the International Phonetic Alphabet are shown between brackets):

Other letters, mainly j and v, appear in English loanwords. Vowels marked with an accent are long. Any accented vowel is pronounced, and vowels next to it usually not; the function of the latter is to indicate the quality of neighboring consonants (broad or slender).

*[dʒ] is written j

*[ç] and [x] are written ch.

*[v] and [w] are written v, bh, mh

*[ɣ] is written dh, gh

*[ŋ] is written ng

*[ɲ] is written nn

*[ʎ] is written ll

*[r] is written rr

Morphology

-

Nominal

-

•case: common, genitive. Modern Irish hast lost most of the cases present in Old Irish.The common case is used for subject and object and it is unmarked. The genitive, besides indicating possession, is used in partitive constructions (part of a whole) and after verbal nouns in progressive constructions.

-

•gender: masculine, feminine. Nouns ending in a broad consonant are often masculine, and those ending in a slender consonant are often feminine.

-

•number: singular, plural. Plural formation is quite complex, varying from noun to noun. Many nouns ending in a short vowel or in ín, óir, and éir form their plural by adding the suffix -í. Other common plural marker suffixes are: -a, -ta, -acha, -anna.

-

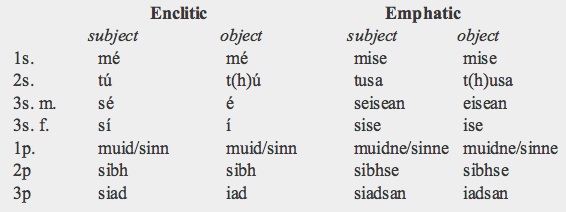

•pronouns: personal, demonstrative, possessive, interrogative.

-

Personal pronouns may function as subject or object. As subject, they follow the verb, as part of the conjugation system, to indicate person and number. Object pronouns have generally the same form as subject pronouns, but a few are different. As the object of a preposition, they are fused with it (prepositional pronouns). They have enclitic, unstressed forms, that can never stand alone and full, emphatic forms.

-

Possessive pronouns are placed before the possessed noun, triggering an initial consonant mutation in it. They are mo (‘my’), do (‘your’), a (‘his/her’), ár (‘our’), bhur (‘your’ [pl.]), a (‘their’).

-

Demonstrative pronouns recognize three deictic degrees: proximal, intermediate, and distal. The three demonstratives, seo, sin, siúd, always occur with the article and don’t have plural forms. They can also be used as pronouns in combination with the enclitic third-person pronouns.

-

The interrogative pronouns are cé (‘who?, what?’), cad/céard (‘what?’), cá (‘which?)’.

-

•articles: Irish has a definite article but not an indefinite one. It has singular (an) and plural (na) forms. Exceptionally, singular feminine nouns in the genitive case use na. Various consonant mutations are linked to the use of the article.

-

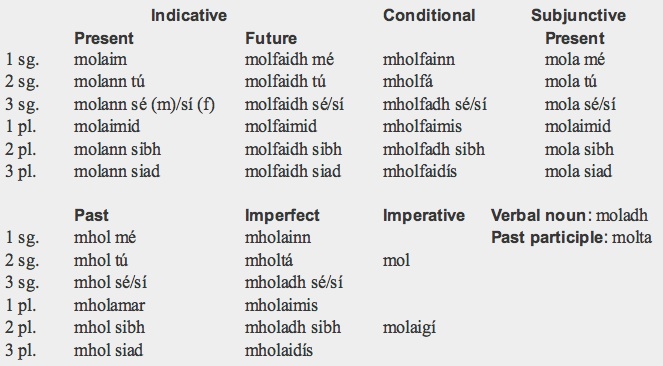

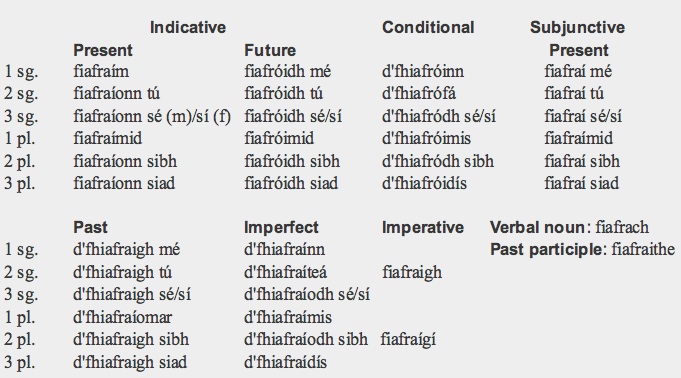

Verbal. The verb stem is the same as the imperative singular. Irish has two classes of verbs, I and II, differing slightly in the endings they take. Most class I verbs have one-syllable stems, class II verbs have mostly two-syllable stems (conjugation paradigms are shown at the end of this section).

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s (masc, fem); 1p, 2p, 3p. They are indicated by personal endings or by personal pronouns placed after the verb.

-

•tense: present, past, imperfect (habitual past), future.

-

Present tense formation differs for the 1st, and 2nd-3rd persons. The 1st person present (singular and plural) is made by adding a specific personal ending to the stem. In contrast, the 2nd and 3rd person presents (singular and plural) are formed by attaching the tense marker ann or eann to the stem followed by a separate pronoun to indicate person and number.

-

The future adds the tense marker faidh/fidh (verb class I) or óidh/eoidh (verb class II) to the stem while person and number are indicated by a separate pronoun, except for the 1st person plural which has a specific personal ending.

-

The past tense of both verb classes is made by lenition of the initial consonant of the stem. Person and number are indicated by a separate subject pronoun, except for the 1st person plural. Verbs starting with a vowel or with f are preceded by the particle d'.

-

The imperfect or past habitual is formed in two ways. For the 3rd person singular and 2nd person plural, the tense markers adh (class I verbs) or íodh (class II verbs) are suffixed to the stem followed by a separate pronoun to indicate person and number. The other persons add personal endings specific of the imperfect, instead of the tense marker. In all persons there is lenition of the initial consonant and, if the verb starts with f , addition of the particle d' (as in the past tense).

-

•aspect: progressive, habitual, perfective. The Irish verb distinguishes between progressive and habitual action in the present and imperfect tenses.

-

•mood: indicative, imperative, subjunctive, conditional.

-

The imperative singular is identical to the verb stem; its plural adds the ending (a)igí.

-

The subjunctive signals an uncertainty about an event that has not yet occurred. It has present and past tenses. In the spoken language is rarely used, the present subjunctive being replaced by the future, and the past subjunctive by the conditional. Both subjunctive tenses are introduced by the particle go (that, until) or, less frequently, by another subordinating particle. The present subjunctive is formed by adding a vowel suffix to the stem: -a or -e for class I verbs, í for class II verbs. Only the 1st person plural form has a personal ending, the other persons-numbers being indicated by separate pronouns. The past subjunctive is identical to the imperfect tense. It is used when the main verb is past or conditional.

-

The conditional is formed by adding endings similar to the imperfect to the lenited future stem, except in the 3rd singular and 2nd person plural which are followed by personal pronouns.

-

•non-finite forms: verbal noun, past participle. Irish has no infinitive. The verbal noun in Irish fills the role undertaken by infinitives and gerundives in other languages. Verbal nouns are formed by the addition of affixes to a basic root.

-

•conjugation examples:

-

a)Conjugation of mol (‘to praise’), a class I verb

-

b)Conjugation of fiafraigh (‘to ask’), a class II verb

Syntax

Irish word order is Verb-Subject-Object. The subject can be a noun, a pronoun, or a nominal phrase, or it might be indicated by the personal ending of the verb. When there is no separate pronoun, the object immediately follows the verb and if there is no object or other information expressed, the verb and its suffix alone may form a complete sentence.

The direct object usually precedes the indirect one, but if the direct object is expressed by a pronoun, it will be placed at the end of the sentence. Additional information, about time, place, other people or things involved follows the verb and any subject or object nouns.

The definite article, possessive pronouns, most numbers, and some words expressing quantity precede the noun, but adjectives usually follow it. So do the demonstratives. Adjectives used attributively, agree with their nouns in gender, number and case.

As Modern Irish has just two cases, a variety of prepositions is used to indicate syntactical relations. Prepositions might add object pronouns as suffixes (known as prepositional pronouns).

Lexicon

Irish has borrowings from Latin, French and English.

Basic Vocabulary

one: aon, amháin (form to count particular objects)

two: dó, dhá (form to count particular objects)

three: trí

four: ceathair, ceithre (form to count particular objects)

five: cúig

six: sé

seven: seacht

eight: ocht

nine: naoi

ten: deich

hundred: céad

father: athair

mother: máthair

brother: deartháir

sister: deirfiúr

son: mac

daughter: iníon

head: ceann

eye: súil

hand: lámh

foot: cos

heart: croí

tongue: teanga

Key Literary Works (forthcoming)

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-'Irish'. D. P. Ó Baoill. In The Celtic Languages, 163–229. M. J. Ball & N. Müller (eds). Routledge (2009).

-

-Modern Irish: Grammatical Structure and Dialectal Variation. M. Ó Siadhail. Cambridge University Press (1989).

-

-Basic Irish. A Grammar and a Workbook. N. Stenson. Routledge (2008).

-

-Intermediate Irish. A Grammar and a Workbook. N. Stenson. Routledge (2008).

-

-The Irish Literary Tradition. J. E. Caerwyn Williams & Patrick K. Ford. University of Wales Press (1992).

Irish

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania