An insatiable appetite for ancient and modern tongues

Classification: Indo-European, Celtic, Insular Celtic, P-Celtic, Brythonic.

According to one hypothesis, Celtic languages are divided into P-Celtic and Q-Celtic. P-Celtic links the Brythonic insular languages (Welsh, Cornish, Breton) with continental Gaulish. Q-Celtic links the Goidelic insular languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx) with continental Hispano-Celtic. In P-languages the Proto-Celtic labiovelar *kʷ became p; in Q-languages it became k.

Overview. Along with Irish, which belongs to a separate branch, Welsh is the most important Celtic language not only by the relative abundance of its speakers but also by its antiquity and by the richness of its literature that is now a millennium an a half old. The Celts reached the British Isles from eastern and central Europe in 600-500 BCE but the earliest records of Insular Celtic languages are from, almost, one-thousand years later (with personal names in Irish and Welsh).

The sound system of Welsh is quite complex and, like in all Celtic languages, the initial consonant of many words may change by morphological or syntactical reasons. Another distinctive feature is that in the sentence the verb appears first followed by subject and object.

Distribution and Speakers. Nearly all speakers of Welsh are bilingual (Welsh-English). Their total number is about 800,000, the vast majority of them living in the United Kingdom (mainly in Wales and England); there are also some expatriates in the Patagonia region of Argentina (5,000), USA (2,500), and Canada (2,200). The Welsh colony in Patagonia was established in 1865 and is based in the towns of Trevelin, Gaiman and Trelew in the province of Chubut.

Status. Until the end of the millennium, the number of Welsh speakers was declining, but in the last decade it has increased due to consistent institutional support. About 22 % of the population of Wales speaks it (half of them fluently). Since the same year, the teaching of Welsh has become compulsory in all schools in Wales up to age 16, helping to reverse the declining trend. Most road signs in Wales are bilingual, there is a TV channel broadcasting solely in Welsh, and a weekly newspaper in Welsh.

Varieties. The spoken language has several regional varieties grouped into North Wales and South Wales dialects, distinguished above all by pronunciation. Besides, there is Literary Welsh employed in literature and in formal situations that has little regional variation.

Oldest Documents

-

•The first records of a British language are personal names from the 5th century appearing in Latin inscriptions found in Wales.

-

•In the 6th c., Taliesin wrote odes in praise of his lord, Urien of Rheged, a kingdom in present-day southwest Scotland and northwest England.

-

•Also in the 6th c., Aneirin wrote the poem Y Gododdin, commemorating in elegies an expedition sent from Gododdin (where Edinburgh stands today) to take Catraeth (Catterick, North Yorkshire) from the invading Saxons.

Periods

Early Welsh (6th–8th c. CE).

Old Welsh (9th-11th c. CE ) becomes differentiated from Old Breton and Old Cornish.

Middle Welsh (12th–15th c. CE) is defined mainly by the Mabinogi, a collection of stories in prose. The orthography and vocabulary are quite similar to the modern language but word order in the sentence is not verb-initial like in Modern Welsh.

Modern Welsh (16th c. CE-present) beginnings are marked by the printing of the Bible in 1588 and by the poetry of Dafydd ap Gwylim.

Phonology

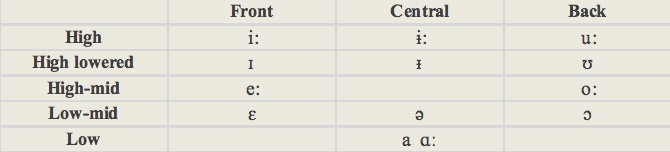

Vowels. Welsh has 13 simple vowels and 14 diphthongs.

-

a) Monophthongs (13): Welsh has short and long vowels. In North Wales (that has the more complex vowel system), they are grouped in six pairs plus the schwa (the unstressed central vowel ə). Members of a given pair differ in length but there are also associated differences in quality. Back vowels are rounded while the rest are unrounded. Southern Welsh lacks the two high central vowels which are realized by the high front vowels.

-

The six shirt-long pairs of vowels are: [ɪ]-[i:], [ɛ]-[e:], [ᵻ]-[ ɨ:], [a]-[ɑː], [ʊ]-[u:], [ɔ]-[o:].

-

b) Diphthongs (15): North Welsh has 15 diphthongs; in some, the first sound is short and in others it is long. They are divided into three sets according to their final element:

-

ei, ai, ʊi, ɔi ɨu, ᵻu, ɛu, əu, au, ou eɨ, aɨ, ɑɨ, ʊɨ, ɔɨ

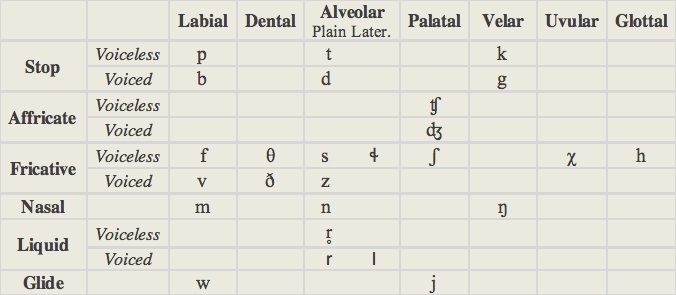

Consonants (26). The inherited consonantal system of Welsh has contrasting voiceless-voiced stops at three articulation points (labial, alveolar, and velar). It has also paired voiceless and voiced fricatives in labial, dental, and alveolar position. The remaining fricatives are voiceless and have no voiced counterpart. The voiceless lateral fricative is unusual in western European languages. [z] as well as the two affricates are borrowed from English and are encountered, mainly, in loanwords.

The rolled r (or trill) is voiceless in word-initial position but voiced in medial or final position (they are allophones and not two different phonemes).

Initial consonant mutation. Like other Celtic languages, Welsh has initial consonant mutations triggered by a great diversity of grammatical features. There are three types of initial consonant mutation: lenition or soft mutation, nasal mutation and spirantization. Lenition occurs in a wide variety of contexts, while the other mutations are more restricted in scope.

a) Lenition (soft mutation). Many lexical items trigger it. Voiceless stops become voiced, voiced stops become fricatives, voiceless fricatives and liquids become voiced, [m] becomes [v] (when required, the symbols of the International Phonetic Association are shown between brackets):

-

p→b; t→d; c [k]→g; b→f [v]; d→dd [ð]; g→zero; ll [ɬ]→l; rh [r̥] → r; m→f [v]

For example lenition is triggered when:

-

1)feminine singular nouns are preceded by the article:

-

mam (mother) → y fam (the mother)

-

pobl (people) → y bobl (the people)

-

2)an adjective follows a feminine singular noun:

-

pobl (people) + da (good) → pobl dda (good people)

-

3)in a compound word the adjective precedes a masculine or feminine noun (the adjective doesn't mutate but the noun does):

-

crom (bowed) + bach (hook) → cromfach (bracket)

-

4)a noun is preceded by some pronouns:

-

dy (your) + tad (father) → dy dad (your father)

-

pa (what?)+ math (sort) → pa fath (what sort?)

-

5)a noun follows a preposition:

-

o (from) + llaw (hand) + i (to) + llaw (hand) → o law i law (from hand to hand)

-

heb (without) + gwaith (work) → heb waith (without work) [g was lost]

Besides these, there are other circumstances that can trigger lenition.

b) Nasal mutation. When the 1st person possessive pronoun fy (‘my’) occurs before a noun, or a noun follows the preposition yn (and also after some numerals), stops shift to the corresponding nasals, the voiceless stops with an aspirate offglide.

-

p→mh; b→m; t→nh; d→n; c [k]→ ngh [ŋh]; g→ ng [ŋ]

-

plant (children) → fy mhlant (my children)

-

Testament → yn Nhestament Newydd (in the New Testament)

-

car (car) → fy nghar (my car)

-

blynedd (years) → pum mlynedd (five years)

c) Spirant mutation. Following the numerals three (tri) and six (chwe), the voiceless stops become voiceless fricatives.

-

p→ph [f]; t→th [θ]; c→ch [χ]

-

pen (head) → tri phen (three heads)

-

torth (loaf) → chwe thorth (six loaves)

-

cae (field) → tri chae (three fields)

Stress: falls usually on the penultimate syllable.

Script and Orthography

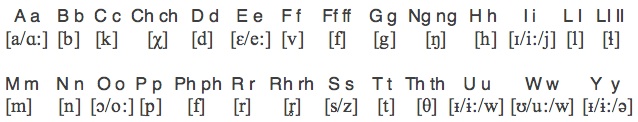

Welsh is written in the Latin alphabet, employing various digraphs to represent basic sounds. Another orthographic particularity is the use of w to represent the consonant [w] as well as the vowels [ʊ/u], and the use of i to represent the consonant [j] and the vowels [ɪ/i:].

*[ð] is written with the digraph dd.

*[ʃ] is represented by si in all positions except final when sh or s is used.

*[ʧ] is represented by the trigraph tsh.

*[ʤ] is symbolized by j.

Morphology

-

Nominal

-

•gender: masculine, feminine.

-

In animate nouns gender coincides with sex. Feminine nouns can be formed by adding -es to the masculine or by changing the masculine endings -yn, -wr, -(i)wr for the feminine ones -en, -es, -wraig/-reg, respectively.

-

Some nouns have a different form for each gender, such as: tad (‘father’), mam (‘mother’), brawd (‘brother’), chwaer (‘sister’), etc. Some nouns have their own gender regardless of sex:

-

a) masculine plentyn (‘child’), barcud (‘kite’), deiliad (‘tenant’)

-

b) feminine: cath (‘cat’), tylluan (‘owl’), ysgyfarnog (‘hare’).

-

The gender of inanimate objects and abstractions is masculine for the names of seasons, months, days, points of the compass, materials or substances. Feminines are the names of foods and drinks, countries and regions.

-

•number: singular, plural.

-

Traces of a dual number survive in words referring to parts of the body that come in pairs; they are, in fact, compounds whose first member is the number two (deu/dwy).

-

The plural is formed by different mechanisms:

-

1) change of internal vowel: llygad (‘eye’), llygaid (‘eyes’).

-

2) addition of a plural ending (au, iau, on, ion, i, ydd, etc): cae (‘field’), caeau (‘fields’).

-

3) change of internal vowel + a plural ending: awr (‘hour’), oriau (‘hours’).

-

4) loss of singular ending (yn or en): mochyn (‘pig’), moch (‘pigs’).

-

5) loss of singular ending + internal vowel change: meipen (‘turnip’), maip (‘turnips’).

-

6) substituting a singular ending for a plural one: planhigyn (‘plant’), planhigion (‘plants’).

-

7) replacing a singular ending for a plural one + internal vowel change:

-

teclyn (‘tool’), taclau (‘tools’).

-

•adjectives: most lack plural and feminine forms. There are four degrees of comparison of the adjective: absolute, equative, comparative and superlative. The last three are derived from the absolute by adding, respectively, the suffixes -ed, -ach, -af e.g.: dewr (‘brave’), dewred (‘as brave as’), dewrach (‘braver than’), dewraf (‘the bravest’).

-

•adverbials: there are only a few simple adverbs. Most are formed by a preposition plus a noun, a preposition plus an adjective, demonstratives connected to a preposition, a preposition plus the article or pronoun plus a superlative adjective, nominal groups expressing time, etc. Adjectives may also function as adverbs.

-

•article: there is only a definite article which can adopt the forms yr, y, ’r:

-

‣yr: before vowel, diphthong, h, between a word ending in a consonant and one beginning in a vowel or diphthong:

-

yr afal (‘the apple’); yr aur (‘the gold’); yr haf (‘the summer’)

-

‣y: before a consonant (except h), as well as between two consonants:

-

y dyn (‘the man’); y wal (‘the wall’); ger y dref (‘near the town’)

-

‣’r: after a vowel or a diphthong:

-

i’r anifail (‘to the animal’); mae’r dyn (‘the man is’).

-

•pronouns: personal, possessive, demonstrative, interrogative, relative.

-

Personal pronouns are independent or dependent. The independent pronouns may stand alone and function as subject or object in a sentence. They distinguish gender only in the 3rd person singular. They have simple, reduplicated or conjunctive forms. The reduplicated forms are used for emphasis (eg. 'you and not anyone else'). The conjunctive forms imply contrast or emphasis (e.g. 'I also').

-

Dependent pronouns may be proclitic or affixed. The proclitic are possessive pronouns that precede the head noun. When a possessive pronoun cliticizes to a preceding word it adopts the affixed form. Object pronouns may also adopt the affixed form following a sentence-initial particle.

-

*The 1 sg. pronoun appears as i following a verbal inflection or to repeat or emphasize a previous pronoun.

-

*Forms between brackets are colloquial (fo is used in North Wales, fe in South Wales).

-

*There are alternative 3rd person affixed pronouns. When they function as possessives,’w may be used after the preposition i (‘to’) for the singular or plural. When they function as direct object, -s may be suffixed to ni, na, oni, pe, in formal Welsh, for the singular or plural.

-

Demonstrative pronouns distinguish two deictic degrees (‘this/that’).

-

In the singular they have masculine, feminine and neuter forms; in the plural there is no gender distinction. The neuter forms may be used with masculine or feminine nouns in informal speech.

-

The interrogative pronouns are pa (‘what?’) and pwy (‘who?)’.

-

The relative pronoun a is used as subject or object of the verb of a relative clause; it is followed directly by the verb.

-

•prepositions: some prepositions can inflect to mark number and person. Among these prepositions are: at (‘to’), i (‘to’), o (‘from’), ar (‘on’), rhwng (‘between’), heb (‘without’), hyd (‘until’), yn (‘in’), etc. There are other prepositions which do not have personal forms.

-

•compounds: can combine nominal and verbal elements:

-

noun + noun: march (horse) + nerth (power) > marchnerth (horsepower)

-

adjective + noun: glas (green) + bryn (hill) > glasfryn (green hill)

-

adjective + adjective: du (dark) + coch (red) > dugoch (dark red)

-

noun + adjective: troed (foot) + noeth (bare) > troednoeth (barefoot)

-

noun + verb: croes (cross) + holi (examine) > croesholi (cross-examine)

-

adjective + verb: cyflym (quick) + rhedeg (run) > cyflym redeg (run quickly)

-

Verbal

-

•person and number: 1s, 2s, 3s; 1p, 2p, 3p. There is also an impersonal form used when no reference is made to any agent (it was seen, it was recognized, it rains).

-

•aspect: perfective, imperfective.

-

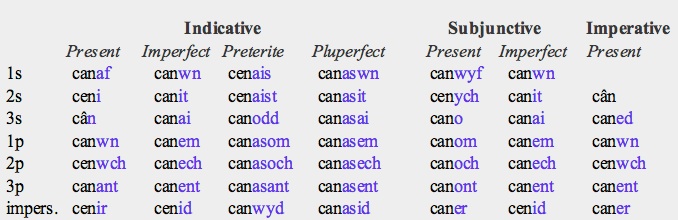

•mood: indicative, subjunctive, imperative. The subjunctive is seldom used nowadays and is restricted, mainly, to unreal, conditional clauses and fixed expressions.

-

•voice: active, passive.

-

•tense: present, imperfect, preterite, pluperfect (rare).

-

The indicative mood has all four tenses, the subjunctive has present and imperfect, and the imperative has only present tense. The present tense has usually a future meaning. The pluperfect is only used in very formal literary Welsh.

-

These tenses are formed by adding a specific set of personal endings to the stem of the verbal noun. The conjugation of the regular verb canu (‘to sing’) is:

-

Verbal Noun: canu; Stem: can; Verbal adjectives: canadwy, canedig

-

•non-finite forms: verbal noun, verbal adjectives.

-

Insular Celtic lacks the infinitive form found in most Indo-European languages. Its equivalent is the verbal noun. The verbal noun is the citation form of the verb (the one found in a dictionary). It is a masculine noun that can take the definite article as well as adjectives e.g. canu da (‘good singing’) and some (but not all) prepositions. It can also form part of verbal constructions with an auxiliary verb. Verbal nouns can be formed by the stem plus a suffix or by the stem alone. Those that carry a suffix derive from a noun or adjective. The suffixes of most verbal nouns are -u, -o, -i, -io, -a, -au:

-

without suffix with suffix

-

siarad (speak, speaking) can + -u = canu (sing, singing)

-

darllen (read, reading) crib + -o = cribo (comb, combing)

-

cadw (keep, keeping) rhodd + -i = rhoddi (give, giving)

-

Verbal adjectives are the equivalent of the English past participle and are formed with the stem plus a suffix or sometimes without any suffix: clo (‘locked’), planedig (‘planted’), agored (‘open’), caead ‘(closed’).

Syntax

In contrast with most Indo-European languages, in Celtic languages, Welsh included, word order in the sentence is Verb-Subject-Object. The verb comes first in affirmative, negative and interrogative sentences. It is frequently preceded by a particle. The direct object precedes the indirect one. Adverbials follow the object.

-

part V (1s past) S DO IO ADVERB

-

Mi roddes i lyfr da i dad Eleri ddoe

-

gave I book good to father Eleri yesterday

-

I gave Eleri's father a good book yesterday.

The subject is differentiated from the complements because it generally experiences sound mutation. When the subject is a pronoun, the verb agrees with it in person and number but when the subject is realized by a noun, the 3rd person singular of the verb is used and there is no agreement between subject and verb:

-

Rhedodd y bechgyn drwy’rardd.

-

ran (3sg) the boys through the garden

-

The boys ran through the garden.

The order in the noun-phrase is: article-demonstrative-numeral-noun-adjective. Singular adjectives may accompany plural nouns, and masculine ones may qualify feminine nouns. Demonstrative pronouns can be used as substantives or adjectives.

Negative sentences use na/nad, before the verb to negate. In direct and indirect questions, the particle a precedes the verb. Questions expecting an affirmative answer are preceded by oni(d)/ai.

Lexicon

The core vocabulary is Celtic but there are many Latin loanwords borrowed during the Roman occupation (first four centuries CE). Welsh borrowed also many terms from English.

Basic Vocabulary

one: un

two: dau (m), dwy (f)

three: tri (m), tair (f)

four: pedwar (m), pedair (f)

five: pump, pum (before nouns)

six: chwech, chwe (before nouns)

seven: saith

eight: wyth

nine: naw

ten: deg, deng (before initial nasal)

hundred: cant, can (before nouns)

father: tad

mother: mam

brother: brawd

sister: chwaer

son: mab

daughter: merch

head: pen, pennaeth

face: wyneb

eye: llygad

hand: llaw

foot: troed

heart: calon

tongue: tafod

Key Literary Works

late 6th c. Poems. Taliesin

-

A dozen poems addressed to several British leaders praising their warlike feats, some of them containing vivid battle descriptions.

late 6th c. Y Gododdin (The Gododdin). Aneirin

-

A long heroic poem, containing a series of elegies, commemorating a disastrous expedition against the English by a band of the Gododdin, a British tribe of southern Scotland.

-

c. 875 Edmyg Dinbych (The Eulogy of Tenby). Anonymous

-

A poem of reconciliation between a poet and his dead lord addressed to his heir.

-

XII c. Hirlas Owain (Owain's Long-Blue Drinking Horn). Owain Cyfeiliog

-

A celebration of the successful rescue of Owain's brother by an expedition headed by Owain himself, prince and poet. The warriors have gathered at his court where each in turn drink mead from the horn.

-

1282 Elegy for Llywelyn ap Gruffudd. Gruffudd ab yr Ynad Coch

-

One of the most famous poems in Welsh, it laments the fall of "the last prince" who died fighting the English in 1282. Alliteration and monorhyme are used in combination with the repetition of phrases to achieve a powerful effect.

XI-XIII c. Mabinogion. Anonymous

-

A collection of eleven tales based on mythology, folklore, and heroic legends, from an older oral material divided in three groups. The first group (XI c.) includes four stories (Pwyll, Prince of Dyvet, Branwen, daughter of Llyr, Manawyddan, son of Llyr, Math, son of Mathonwy) which are the finest of the collection and deal with fundamental aspects of Celtic mythology. In the second group (XII c.), including Culhwch Ac Olwen, The Dream of Rhonabwy, Lludd and Llefelys, The Dream of Macsen, appears Arthur the mythical hero surrounded by his renowned companions. The tales of the third group, Owein and Luned or The Lady of the Fountain, Geraint and Enid, Peredur Son of Efrawg, were influenced by the French romances Yvain, Erec, and Perceval of Chrétien de Troyes.

-

1340–70 Poems. Dafydd ap Gwilym

-

The most distinguished of Medieval Welsh poets, he introduced linguistic and metrical innovations as well as new subjects. It seems he borrowed his themes from the wandering minstrels of France. He wrote love poetry and fine descriptions of nature.

-

1854-56 Y Storm (The Storm). Islwyn (William Thomas)

-

Two long poems (6000 lines each), bearing the same title, written after the death of a young woman to whom he was engaged to be married, a meditation on life and art, romantic and metaphysical.

-

1928-70 Poems and essays. Thomas Parry-Williams

-

Poet and essayist, he combined mystical sensibility and linguistic directness with an analytical observation of nature.

-

1921-80 Plays. Saunders Lewis

-

Besides poems and literary criticism, he wrote nineteen plays which are considered his most significant contribution to Welsh Literature. A Roman Catholic and nationalist, influenced by the writers of the French Catholic revival, his plays deal with honor, leadership and politics.

-

© 2013 Alejandro Gutman and Beatriz Avanzati

Further Reading

-

-The Welsh language. J. Davies. University of Wales Press & The Western Mail (1999).

-

-A Comprehensive Welsh Grammar. D. A. Thorne. Blackwell (1993).

-

-'Welsh'. G. Awbery. In The Celtic languages, 374-426. M. J. Ball & N. Müller (eds). Routledge (2009).

-

-A Guide to Welsh Literature (6 vols). Several editors and authors. University of Wales Press (1992-2000).

-

-The Oxford Companion to the Literature of Wales. M. Stephens. Oxford University Press (1990).

Welsh

Address comments and questions to: gutman37@yahoo.com

MAIN LANGUAGE FAMILIES

LANGUAGE AREAS

Languages of Ethiopia & Eritrea

LANGUAGES by COUNTRY

LANGUAGE MAPS

-

• America

-

• Asia

-

Countries & Regions

-

-

Families

-

• Europe

-

• Oceania